Overthrow by Pragmatism: Obama’s Cuban Strategy

Every president needs a doctrine. Now the sensible approach here would be to see the need for a doctrine the way an ardent feminist might see the usefulness of a man. As Irina Dunn claimed (an aphorism commonly attributed to Gloria Steinem), “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.”

Be that as it may, President Barack Obama’s doctrine has been deemed to be “much less a coherent foreign policy ideology than a basic recognition of the world as it is: the moral dilemmas of American power in a post-Iraq world make anything as simplistic as an ideology at best silly and at worst destructive.”

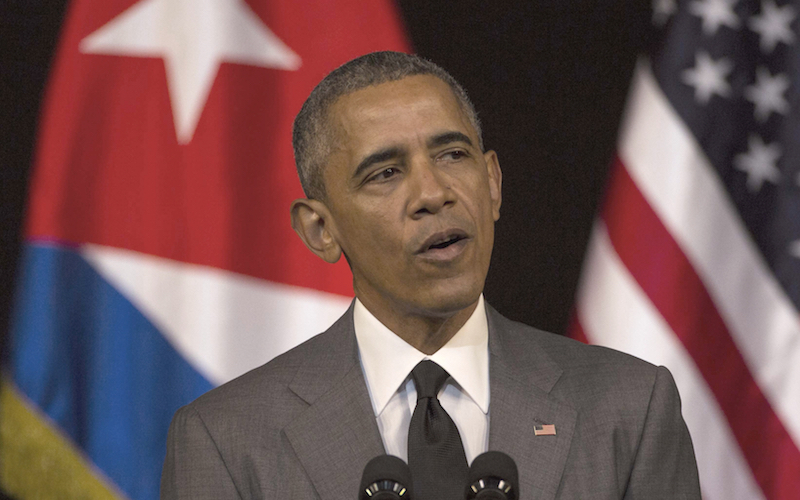

Obama’s Cuban adventure may not have involved the school boy bravura of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, all patriotic gore dictated upon saddles in a quaint imperial tradition. But nor was it entirely free from ideology. There was no getting away from the fact that this play for the cameras as he touched down on Cuban soil was very much in the order of historical show. He was there to enact a ceremony of US power.

On Monday, he exclaimed on Twitter how “Michelle, the girls, and I are here in Havana on our first full day in Cuba. It’s humbling to be the first US president in nearly 90 years to visit a country and a people just 90 miles from our shores.”

The White House site, however, evinced a more serious approach, one unmistakably tactical in attempting to reform, not so much the Cuban-US relationship, as Cuba itself. (Ignore the point that Cuba has much to teach the US, notably in terms of social welfare.) It was clear that Obama was keen to “promote a democratic, prosperous and stable Cuba.”

This has taken various forms, first with the May 29, 2015 rescinding of Cuba’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism, followed by the reopening of the US embassy in Havana, reciprocated by Cuba in Washington on July 20, 2015. There have also been joint initiatives combating narcotics, transnational crime and various agreements on marine activity, the environment and the delivery of mail.

These gestures are plugged into the market model of opening up Cuba, an approach that emphasises the strength of the dollar and the profit motive over the starvation approach of the embargo. This is framed as an effort to help Cuban citizens rather than the hungry ambitions of US business. “Decades of US isolation of Cuba have failed to accomplish our objective of empowering Cubans to build an open and democratic country” (White House, Mar 20).

The description of Obama’s Cuba effort in the US has varied between the Miami-lobby’s conventional, visceral rage and the liberal wing that sees American power as a gentleman’s code of conduct in action, to be exercised responsibly to influence history. “Through a series of tiny gestures,” wrote Stephen Marche in Esquire, “Obama achieved what 50 years of American resistance to Cuba was not able to.” For Marche, Obama was truly a “masterful performer” on “the world stage,” with the “press conference with Raul Castro” being in of itself “a masterpiece.”

The views from the conservative Commentary Magazine, however, emphasise the “ego-fuelled venture to the island prison nation,” with Obama doing his bit to legitimise “the world’s holdout Marxist regimes.” Noah Rothman, almost charmingly anachronistic, was still attempting to identify the tricks of the trade Havana might deploy against the US government. (What, asked Rothman, of the mysterious case of a Hellfire missile delivered to Havana from Europe, one duly surrendered to the US ahead of the visit?)

If the outcome of this US-Cuban rapprochement is a pale admission to the limits of US power, then sceptics of the global imperial project will have much to take away from it. But this concession to reality will eventually see Washington’s business interests reassert themselves in traditional territory, and with traditional mercenary zeal. Those grateful for Obama’s tactics here see a way of ambushing the communist regime and providing fodder for its overthrow.

Pragmatism, in other words, can be a state’s most poisonous asset, deployed under the guise of realistic worth. It was for such reasons that, in the words of Mexico’s former secretary of foreign affairs Jorge G. Castañeda, Obama, “perhaps even somewhat cynically – decided to abandon trying to compel Cuba’s leaders to change their political system.” Engagement without revolutionary punch.

The sceptics argue that US investment and spending is not likely to lead to the flowering of a thousand flowers of democratic sentiment. There was, asked Rothman, no satisfactory reason “why similar investment over the decades from Canada and Western Europe has not had that effect.” The obvious answer to this is that such investment was minute given the state of the continued US embargo. Pity the dissidents, who find themselves caught up in all of this.

Far from constituting anything supportive of the Castro regime, this neo-Open Door policy is an attempt to strangle by means of a velvet glove. “It does not serve America’s interests, or the Cuban people, to try to push Cuba towards collapse.”

Presidential doctrines continue to be silly things, but if Obama’s is based on a thought through pragmatism when it comes to such regimes as that of Cuba – tolerance for the sake of change over time – it is hardly different from those adopted by previous US administrations. The stance is merely clearer, a clarity of position that will become more obscured with the next president. The very essence of hegemony, it seems, is intervention, by overt force, or stealth.