Polishing Turds: Lord Bell’s Public Relations Revolution

“Morality is a job for priests. Not P.R. men.” – Tim Bell, New York Times, Feb 4, 2018

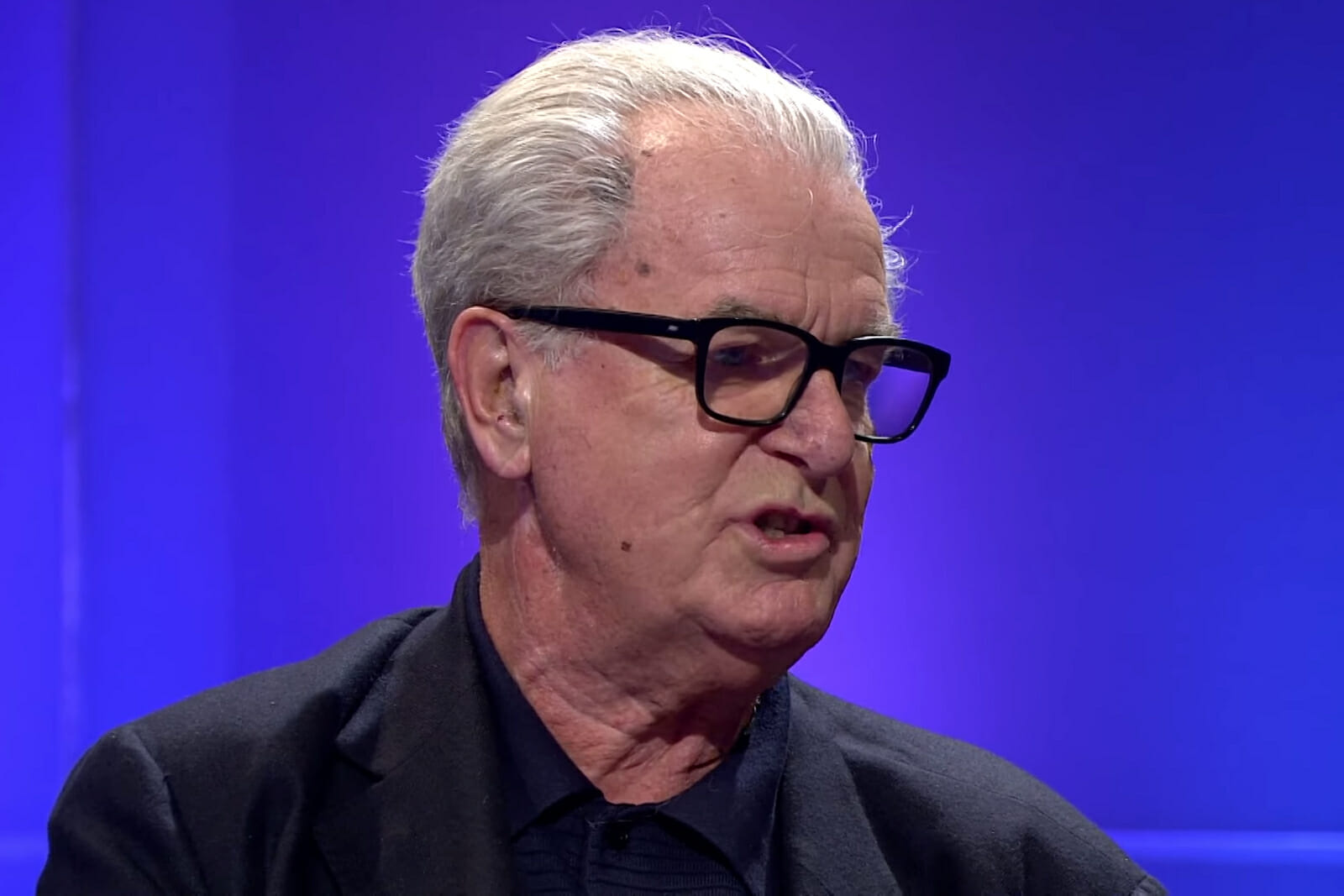

Lord Bell is dead, but his public relations tinkering, with all its gloss gilding and deception, remains. It was Tim Bell who cut his teeth in this dubious field, assisting Margaret Thatcher to win the 1979 UK election through a mix of emotive tugging images with varying degrees of accuracy. It was also Bell who elevated public relations in politics from the level of unpolished turd worship to the level of, well, acceptable turd worship.

Bell’s own preference was for a urinary image, corporate communications seen traditionally as “peeing down your trouser leg – it gave you a nice warm feeling when it first happened, but goes cold and wet pretty quickly.” As he insisted in a 2018 interview with The New Yorker, “What we did was move the public-relations advisers from being senders of press releases and lunchers with journalists into serious strategists.”

He was the master of focused destruction, the devil’s able footman. He had a nose for the malodorous reek of public feeling. Thatcher was impressed by his proudly amoral talents, his instinct to manipulate the record by touching the appropriate nerve. “He could pick up quicker than anyone else a change in the national mood. And, unlike most advertising men, he understood that selling ideas is different from selling soap.”

Bell was credited, over generously, with fashioning the slogan “Labour Isn’t Working” in 1979, one that at the very least helped seduce voters into voting for the iconoclastic Thatcher. He claimed that she was one to worship, a true She-wolf, as he called her with some warmth. “I am a hero-worshipper. I work for my demi-gods.”

As the co-founder of the firm Bell Pottinger, his list of clients of varying degrees of scrupulousness proved extensive. PR will do that sort of thing, an easy way out for the complex problem and thorny dilemma. With the US-led invasion of Iraq going rather badly in 2004, it became clear to the occupation forces that something had to be done about that misunderstood “D” word; democracy would have to be sold, something that Freedom’s Land has not been particularly good at.

In an effort to prevent democracy dying in transit, Bell Pottinger was enlisted by the Pentagon to release a range of radio and television commercials explaining how and why a handing over of sovereignty to an interim Iraq government would take place in June. The British firm was essentially lecturing Iraqis on the joys, and necessities, of that jolly good system, whatever that might have looked like in the PR-world. In Lord Bell’s bland words, “We’re trying to keep people informed about the process and persuade them to participate in it.”

Even some advertisers wondered whether Lord Bell was going a touch too far with this caper, noting that similarly vain and flat-footed efforts had been made by Charlotte Beers in 2001. Can you really advertise democracy? Harry C. Boyte, senior fellow at the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, warned of the dangers of treating democracy as an advertiser’s tarted-up product. If the product goes pear-shaped, democracy would then be held to blame.

Other notables on the retainer list included the wife of Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad, Asma, who wound her way into Bell’s portfolio in 2006 desperate to join other first ladies and female leaders who had sought the services of the firm. “She wanted to be part of that club,” mused Bell in an interview with the New York Times. Something obviously worked: Mrs. Assad was subsequently celebrated in the Huffington Post for her “All-Natural Beauty”; praised in French Elle as one of the world’s best-dressed women in politics, and dreamily described by Paris Match as the “eastern Diana” with an “element of light in a country full of shadow zones.”

Military despots such as Chile’s Augusto Pinochet could also count on his services. In 1998, Bell assisted the Pinochet Foundation in mounting a vigorous campaign to frustrate efforts to extradite the General to Spain on charges of murder and torture.

South Africa proved a particularly happy hunting ground. Former SA president FW de Klerk was counted as a client, as was the troubled athlete Oscar Pistorius. But it was also South Africa that would prove the firm’s undoing. Unfortunately for Bell and business partner Piers Pottinger, their clients, the Gupta family, proved a hard, and ultimately fatal sell. Ajay, Tony, and Atul Gupta had reaped the rewards of a rich relationship with President Jacob G. Zuma, one that yielded contracts in mining, railways, and armaments. But the brothers felt that a distraction from the activities of their holding company, Oakbay Investments, was needed.

Bell Pottinger were then slotted into the picture to confect something appropriate at the monthly cost of $130,000 over a three-month trial period. Local and community black activism was to be encouraged – not in itself a bad thing. The catch was crude but simple: the Guptas’ opponents were to be branded as sponsors of a racist system. The narrative of “white monopoly capital” was pushed through social media and websites (Bell called the theme one of “economic emancipation”), suggesting that white South Africans were on a rampage seizing resources at the expense of education and jobs for blacks.

Stoking racial tensions in South Africa did not go down well, and the company was expelled from the UK’s Public Relations and Communications Association (PRCA). An exodus of clients duly led to the company going into administration. The damage had been done. “Bell Pottinger,” lamented Francis Ingham, director-general of the PRCA, “may have set back race relations in South Africa by as much as 10 years.” Bell was by that point out of the picture, the victim of a boardroom bloodbath engineered by fellow publicist James Henderson.

Business partner Piers Pottinger offers the usual sweet snippets to cover a well-accomplished rogue dedicated to his clients. “He was a devoted family man and passionate supporter of the Conservative Party, most famously helping Margaret Thatcher win three general elections.” Naturally, he was “an inspiration” for those who worked for him. “Most importantly to me, he was always a true and loyal friend. Nobody can replace him.”

Perhaps not Bell, but certainly facsimiles of him, who operate with morally bankrupt impunity in London, a city famed for being a hive of reputational laundering. Despots and unsavoury regimes are queueing for services in numbers and will have much to thank Lord Bell for. After all, he saw good P.R. not merely as a service but an inherent right on par with legal representation.