Red Lines and Syria’s Chemical Weapons

“We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized. That would change my calculus. That would change my equation.” – President Barack Obama

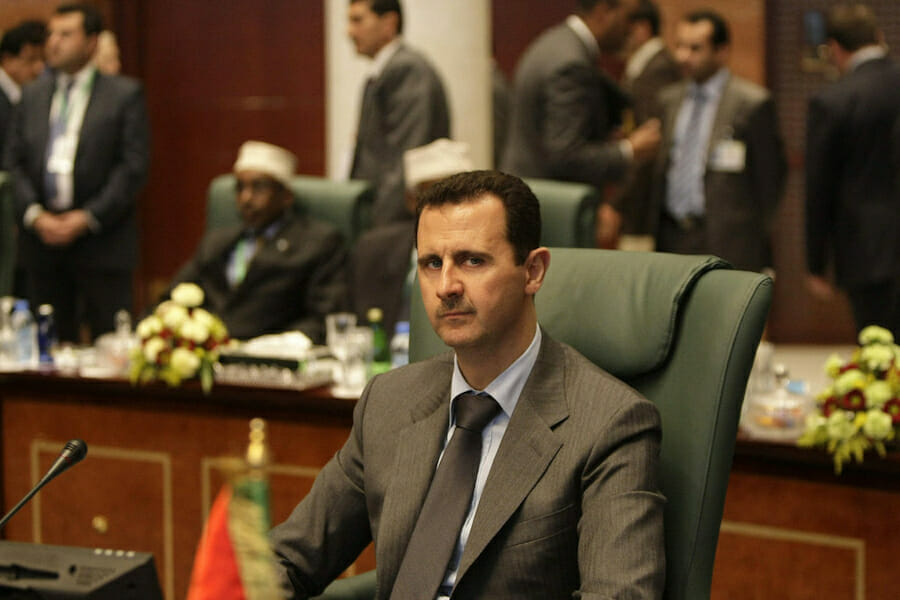

While the Obama administration has for many months stressed the need to give diplomacy another chance to work in Syria, the administration has now decided that if Assad were to employ his vast chemical weapons stockpile against the rebels, the U.S. would have no choice but to intervene in the nearly two-year-old conflict. Fears about the potential fallout of the demise of the Assad regime are running high, as a post-Assad Syria could likely degenerate into a sectarian civil war that would make Iraq look like a picnic, given the complex religious and ethnic fabric of Syrian society.

With the rebels making significant advances throughout Syria and inching closer to the heart of Damascus, the fear is that Assad could launch chemical weapon attacks against rebel positions in a bid to halt their advance.

Employing chemical weapons is not a precision game – numerous factors would impact the success or failure of their use, including prevailing winds. Collateral damage would likely be immeasurable, essentially constituting mass murder on a scale not witnessed in decades. Assad could be using the threat of chemical weapons as a bargaining chip to secure more preferential terms, should he decide to flee – which is becoming increasingly likely.

U.S. Intervention

There is no good option for American or NATO intervention in Syria. Reports have suggested that it could take as many as 60,000 ground troops to secure chemical and biological weapons sites throughout the country. This assumes accurate intelligence, the ability to deploy that size of force quickly, and limited opposition to foreign troops once on the ground. Such intervention would be costly, and assuming elements of Assad’s regime remain, it could prove to be such a hurdle that success could be problematic.

American intervention in Syria could come in a myriad of forms, but two appear the most logical. The first would require the pre-deployment of special operation forces to complete the initial identification and assessment of priority targets. Rumors have been circulating that special operations teams and members of the intelligence community from the U.S. and regional allies have been in Syria for months. Assuming that the foundation has indeed been laid, a push by thousands of ground forces to secure chemical weapon stockpiles and biological weapon agents would be a primary focus.

The second component of American intervention would be in the form of airstrikes, which carries their own risks. If the U.S. acted unilaterally, Syria’s allies – Russia and China – would presumably forcefully object at the UN. If airstrikes failed to destroy significant portions of the stockpiles, a more robust U.S. presence would become necessary. Air strikes by the US and/or NATO allies could also push the Assad regime – and those remaining loyal to him – to the brink. This could be used by the Assad regime as a pretext to use chemical weapons, as it has already warned that it would use such weapons only against foreign threats.

There is no doubt that the U.S. has the ability to carry out such airstrikes; the larger question is whether it has the political will. Given the calamitous outcomes of U.S. intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan, President Obama is surely thinking twice about committing ground troops in Syria.

Until now the Obama administration has demurred from offering assistance to the rebels in the form of heavy weaponry. This cautious position is grounded in previous experience. While the no-fly zone in Libya was successful in facilitating the end of the Qaddafi regime, the plethora of post-conflict weapons floating around Libya that have fallen into the hands of rebels and Islamic extremist factions are surely giving Obama pause. These weapons migrated to other conflict zones – including Mali – and there are some indications that Libyan weapons ended up in Syria as well. Given the toxic mix of groups opposing Assad in Syria, weapons landing in the hands of Islamic extremists is the last thing the West would desire – particularly given the implications for Israel.

Assad’s Final Chapter?

The Syrian crisis has been transformed from a peaceful uprising against the Assad government into a deadly civil war, which has killed tens of thousands. The Syrian rebels are receiving weapons and financial aid from a variety of foreign sources, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and other Middle Eastern states. Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising, concerns regarding the composition of the rebel leadership and its objectives have been reoccurring. In the absence of a clear understanding of what the rebel force would materialize into, many are now openly asking whether the devil we know (Assad) is worse than an unknown devil.

There is no doubt that the noose is tightening on Assad’s regime and it appears just a matter of time before the end game arrives. In the past week, Assad has escalated his military campaign by firing Soviet-era SCUD missiles on some of Syria’s main population centers. As the situation continues to deteriorate, it is possible that Assad will feel he has no other choice than to unleash chemical weapons stockpiles on the rebels, and in the process, on the Syrian people.

The U.S. and NATO face a stark choice, having drawn a line in the sand. There can be little doubt that the use of chemical weapons will indeed trigger American and/or NATO intervention in Syria. If that occurs, the U.S. will quickly find itself engaged in a proxy war it had hoped to avoid not only with Iran but with jihadists from around the Middle East and North Africa, who have been drawn to Syria.

The pendulum has now swung firmly in the rebels’ favor. Assad’s days are clearly numbered. But so is a time when relative peace existed between Syria and Israel, and Syria and Turkey. If a radical Islamist regime assumes power in Syria, not only Israel and Turkey, but also Jordan will feel the heat. Surely, the jihadists will set their sights on Jordan next. For that reason alone, the U.S. is likely considering all options, including what form and shape a more involved intervention would look like to end the civil war and secure Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles. As distasteful as it sounds, yet another long-term commitment to a conflict in the Middle East may be looming for the U.S.