Remembering Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Art

We all have our individual intersections with great art, the personal points of connection that make us feel united in common humanity. When I heard of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s passing, I instantly recalled one of his earliest roles: the preppy rich kid George Willis Jr. in Scent of a Woman (1992). When I first saw the film, I was a child; I came to quick conclusions about it. I thought Willis Jr. manipulative and arrogant. I hated his values unequivocally; I must have seen kids like him at grade school. But there was something about the performance that stayed with me. Over the years I grew to appreciate the conflict within Willis Jr., lit brilliantly by Hoffman. I noticed the actor’s eccentric verbal and physical cues; I noticed the art. Today, looking back at Hoffman’s career as I know it, the role seems typical. Characters on the periphery, no matter how far they descended, became everymen in his hands. He could make the boring insider seem compelling outsider.

I probably saw Scent of a Woman on home video in the 6th grade. Al Pacino’s performance as the bombastic and blind Lt. Col. Frank Slade intimidated me. I could not find my way past his angry exterior. Hoffman’s turn as haughty schoolboy Willis Jr. was closer to my childhood experience. When I think of the actor’s ingenuity, my memory recalls the honor council meeting at the film’s conclusion, where Willis Jr. and his father are seated at a table in the assembly hall of Baird School, on trial for a childish prank against the headmaster.

Superficially, the scene positions Hoffman’s character as a rich, entitled heel. But the performance belies this trope.

When his father whispers in his ear, Willis Jr. jerks his head away in frustration. He grimaces and hides his face from the assembled students. He plays up every doubt in Willis Jr.’s mind, such that his reaction shots as a supporting actor are more interesting than many of the leads’ action shots.

Unquestionably, Willis Jr. deserves scorn for lying and selling out his supposed friend Charlie. But Hoffman fully renders his character, as usual. Willis Jr.’s ambivalence is compelling enough to suggest a backstory; perhaps his delinquency is reaction to his father’s imperiousness.

The next Hoffman film that left a mark on me was Twister (1996). When I saw the movie as a kid, it was less a study in great acting than an opportunity for vicarious adventure. As a teen meteorology enthusiast, I felt drawn to Hoffman’s character, Dustin Davis, the archetypical tornado aficionado. On a team of storm chasers, Dusty aka “The Dustman,” was the most genuine—the most saturated in the trade. After spending just a few minutes with him, watching him gleefully ride from one natural disaster to another, I knew the character.

Dusty’s 80s metal hair flows under a baseball cap and hoodie. He has no compunction about slipping on sunglasses and lecturing the nearest lady on the dangers of a tornado’s “suck zone.” He lives for brief glimpses of twisting black clouds over the Great Plains. “It’s the wonder of nature, baby!” says Dusty, reaching for the volume knob for the hard rock music video playing in his van. On sunny days, he makes do with steak. “Meg’s gravy is famous. It’s practically a food group,” he says. After the movie, I could envision Dusty’s apartment furnishings: a weather radio, a beer fridge, a hot plate, and a wall full of tornado photos and Van Halen posters. And a piece of debris from his first twister.

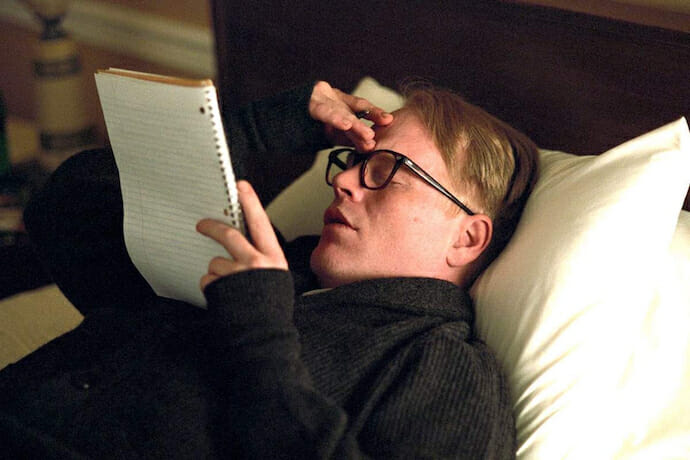

Last year, I saw The Savages (2007), which features one of Hoffman’s best lead roles. Hoffman plays Jon Savage, a Bertolt Brecht scholar writing a book and rebuilding his relationship with his sister Wendy and father Lenny. Jon is every inch the struggling writer, fighting back depression and regret and fatigue about his own career as he looks out for family. He is locked in a room with his work. Repression rules him. Jon could become a lampshade without a gifted actor—one able to convey adamant intellectualism with a heart.

Hoffman understands the uneasy brother-sister bond in The Savages—the line between sibling competition and cooperation. Jon and his sister apply for the Guggenheim Fellowship routinely and let the rejections poison their self-confidence. At times, Jon loses himself in nihilism, which he conflates with realism. His father’s dementia-driven outbursts aggravate the situation, reminding him of the pain inherent in any close relationship. Jon erupts at his sister during a visit to the nursing home: “People are dying, Wendy! Right inside that beautiful building right now, it’s a fucking horror show! And all this wellness propaganda and the landscaping, it’s just there to obscure the miserable fact that people die! And death is gaseous and gruesome and it’s filled with shit and piss and rotten stink!”

With Wendy’s help, he laughs at himself again, rediscovers the goodness in shared blood and shared burdens, and allows room in his life for romance.

Throughout Hoffman’s career, he championed nuance. If a script sketched grayscale, Hoffman introduced a full spectrum of color. The remainder of humanity in the lowest villain was his to command and illuminate.

We will miss seeing Hoffman inhabit some of the great senior roles on stage and screen: struggling salesman Shelley “The Machine” Levene in Glengarry Glen Ross (1984); rapier-witted Professor George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962); and the likewise word-wise, rumpled Rev. Shannon in The Night of the Iguana (1961).

He could have been William Jennings Bryan, Eugene O’Neill, or Elon Musk. Like frequent collaborator Paul Thomas Anderson, he mapped America from every vantage point: risers, crashers, calculators, and giddy followers. Hoffman knew the measure of his commitment to the arts. “It takes something from you to give on that kind of level,” he once said. “To commit that much. What are you willing to risk? What kind of life are you willing to lead to have that? For any serious person doing this, I think that is a question you have to answer. Or at least know that it’s a question.”

Interview Magazine recently recommended Hoffman for the role of Sheriff Willis McCall in the forthcoming film adaption of Gilbert King’s Pulitzer-winning Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America (2012). It’s a tale of persistence against bigotry. The actor ultimately cast as McCall should study Hoffman’s filmography and method to prepare. Only an artist of Hoffman’s discipline could inform the story of race in America.