Remembering the Experience of the Mizrahi: Forgetting History Complicates Peacemaking

The decades-long conflict between Israel and Palestine has prompted endless explorations and policy solutions of varying scopes and efficacy. Despite the surplus of literature pertaining to this conflict, little has been written about the experience of the Mizrahi, the ethnically Arab Jews of the Middle East and Northern Africa.

The horrible mistreatment of the Ashkenazi Jews in Russia and Germany in the 20th century is well-documented. However, since the end of the Second World War, Jewish identity has become increasingly understood as monolithic. This oversimplification of the Jewish experience is problematic, as the experiences of the Ashkenazi varies starkly from other Jewish communities, such as the Mizrahi.

The Arab community, and even the Mizrahi, have criticized this shift in our understanding of history. Scholars like Dr. Ella Shohat argue that the current historical approach is flawed, as it ignores, oversimplifies and sanitizes history. Indeed, the Jews of the Middle East faced different challenges than those of the West, and consequentially have had different experiences.

The Mizrahi of Israel face duality; they are Arabs, but they are also Jews. They have faced ethnocentrism and racism in Israel, yet they themselves are enfranchised and socially accepted compared to the Palestinians. Essentially, the history of Arab Jews must be distinguished by two historical realities: facing social pressures for being both ethnically Arab and religiously Jewish. Secondly, that the experiences they faced in the Middle East were markedly different from those experienced by European Jews.

How Arab Jews Became the Israeli Mizrahi

Originally Arab Jews were accepted and participated in the Pan-Arab context. This changed with the advent of Israel. The Israeli leadership needed to increase Jewish immigration to Israel, so they launched campaigns to divide the Arab Jews and the larger Arab population. The discourse began to frame Zionism and Pan-Arabism as antithetical, leading the Arab people and leadership to see the Arab Jews as outsiders. Shohat, an Arab Jew herself, has argued that the failure of the Arab world to distinguish between Judaism and Zionism was its fatal flaw.

Indeed, the arguments for the removal of Jews from the Arab world played into the anti-Semitic trope of duel-loyalty. That said, Israeli policy itself has exacerbated this divide. Further, Israel engaged in dealings with Arab leaders where they arranged for “population exchanges,” in which they traded Arab Jews for Palestinians. Therefore, the leaders of the Arab world are not exclusively culpable for the expulsion of the Arab Jews, as the Israeli leadership helped arrange this exchange of people.

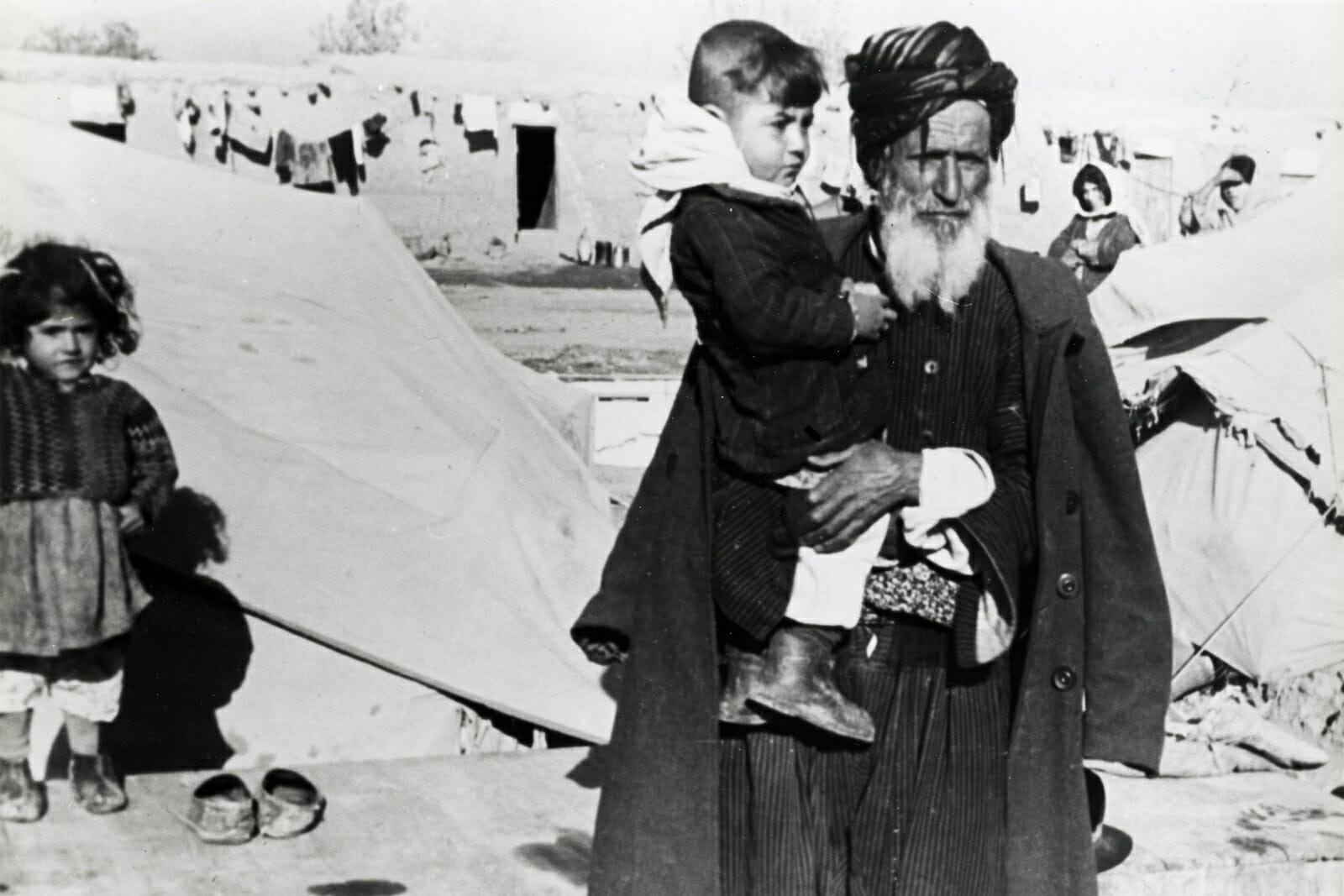

The Arab Jews lost their homes and citizenship, forcing them to flee to Israel. In Israel, this “ingathering” is framed as a joyous return to the homeland. However, for many Arab Jews, they remember the event as a catastrophic loss of home, culture, and identity.

The Arab Jewish Experience in Israel

Upon coming to Israel, the Mizrahi faced marginalization and loss-of-identity. The Israeli leadership sought to sever the Arab Jew’s connection to their “Arabness.” The Mizrahi identity was a top-down attempt to disconnect the Arab Jews from their ethnic pasts. Rather than being an Iraqi Jew or a Baghdadi Jew, the Mizrahi were expected to assimilate not only to this new state, but also to the European cultural norms of the ruling class.

Israel’s founders brought with them not only the culture of the West, but also its orientalist and colonial tropes. Israeli anthropology and sociology at this time referred to the Arab Jews as a primitive, traditional and tribal community antithetical to the modern West. Much was written about how to civilize this eastern community, most sought to assimilate the Arab Jewish communities; others argued that the Mizrahi were racially inferior, advocating against European-Arab interbreeding. The Mizrahi were viewed not as a people with their own culture and histories, but as a problem that needed to be solved.

These problematic attitudes remain in the daily life of the Mizrahi today. Those who wear traditional Arab garb struggle to find work and face persistent racialization in the Israeli media. The most extreme example of European intolerance of Arab Jewish culture occurred in refugee camps during the ingathering. Mizrahi children were separated from their parents, who were told their child had died shortly after birth, and were put up for adoption so the children would grow up in Eurocentric households. The Yemenite Child Affair was only recently recognized by the Israeli government. The figures remain unclear, but most estimate that somewhere between 1,000 to 4,500 children were taken away from their families.

Why Discuss the Mizrahi experience?

Oversimplifying historical suffering by emphasizing one event while ignoring others is always problematic. The Arab Jewish experience in the Middle East was by no means a perfect existence, nor was their experience in Israel marked by constant persecution. The experience of the Jewish people is and will always be complex and multifaceted.

However, highlighting history that many would rather forget has its value. By confronting the past critically, we are forced to rethink what we know about the world.

By confronting uncomfortable patterns, or even aberrations, of behavior we may find new ways of understanding others. Open forums to discuss shared suffering and experiences may provide an opportunity to build relations between not only the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, but also between the Palestinians and the Israelis.