Books

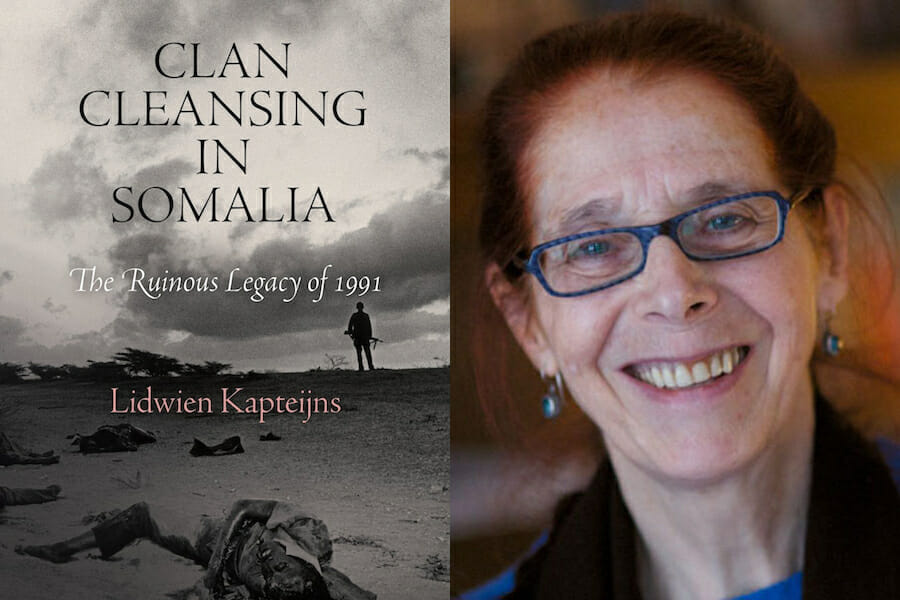

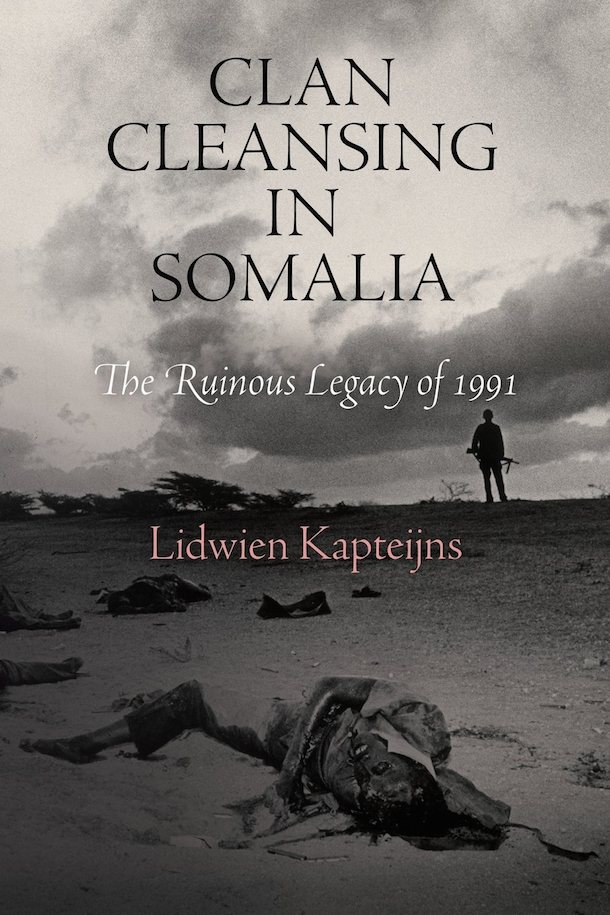

Review of ‘Clan Cleansing in Somalia’ by Lidwien Kapteijns

The publication of Clan Cleansing in Somalia: The Ruinous Legacy of 1991 by Lidwien Kapteijns has triggered bitterness among Somalis. The reason is because the author argues that the Hawiye clan aided and abated by the Isaq clan adopted a policy that defined the Darod clan as an enemy targeted for elimination and expulsion from Mogadishu between January 28, 1991 and December, 1992.

This argument shifts the taxonomy of the Somali conflict from “civil war” to “clan cleansing” which is used as interchangeable with “genocide” and defined as “those cases in which a perpetrator group attempts, intentionally and over a sustained period of time, to annihilate another social or political community from the face of the earth.” Stathis N. Kalyvas of Yale University argues that, as in the case of Somali civil war, rival factions intend to control rather than eliminate the enemy’s constituency from the new state.

As a matter of fact, Darod “representatives” were members of both the governments established in Mogadishu and Hargeisa immediately after the fall of Siad Barre regime. The author does not provide substantive evidence but rather uses a misrepresentation of poems describing the horrors of the civil war, fictional stories and one-sided information provided by anonymous victims. Lidwien Kapteijns uses the Somali civil war as a polemical argument and relies on Ioan Lewis for his scholarship on the Somali clan system. The author dismisses the clan grievances underlying Somali politics and discriminates against the Hawiye clan militia from other clan-based militias. The flawed and distorted analytical framework of Kapteijns could not explain the clan influence and dynamics in Somalia.

The explanation supporting the author’s conclusion of the Hawiye and Isaq clans feeds the conspiracy of Irir alliance (Irirism), that USC (Hawiye) welcomed as heroes Hawiye “henchmen” of the Barre government, who fled their houses after being targeted by the supporters of Barre regime for clan affiliation.

This shows a willful ignorance of the author on the clan alignment in the days leading up to the spontaneous popular uprising on December 29, 1990.

The discovery of the diametrically opposed memories and interpretations of what happened in 1991 by the different parties in the Somali conflict and the lack of evidence that the Hawiye clan created a campaign or policy of clan cleansing (genocide) does not support the author’s claims. The 1991 civil war caused unspeakable destruction and a massive exodus of refugees, but the claim of genocide borders to malevolent intent.

The contradictions in the book are probably attributable to these unverified selective narratives and to the author’s dismissal of the theoretical framework of a balanced clan identity approach as an important analytical tool for the civil war in Somalia. For example, Kapteijns uses the word “absentee” for Hawiye members who fled their homes in the Galkaio district after being expelled by their Darod clan in 1989.

Kapteijns scanned the political violence, which took place in many parts of Somalia before the fall of the Siad Barre regime, as an irrelevant past history of Somalia. Ironically, Kapteijns faults the SNM leaders for provoking the government forces in the urban areas. In her frame of analysis, the mass exodus of Isaq clan from their land was not clan cleansing (genocide). Throughout the book, the author castigates all those who studied, commented or wrote about Somalia for their “cowardice” of not seeing, feeling and publicizing the 1991 genocide campaign perpetrated against the Darod clan. The only exception is Mohamud Togane who received praise for composing satirical poems of the Hawiye and Darod clans, because the author seizes the satirical poems against Darod as an example of hate construct.

It is unfortunate that the author belittles the extraordinary efforts of Hawiye leaders to achieve peaceful political transition by mobilizing the Manifesto Group so as to avoid the disastrous consequences of a civil war in Mogadishu. As confirmed by many sources, the late Mohamed Farah Aidid advocated for a strategy that avoided armed confrontation with government forces inside Mogadishu. But the spontaneous popular uprising in Mogadishu provoked by the nightly mass executions and looting committed by the supporters of the regime changed the dynamics and sparked the civil war on December 29, 1990. Because of the intense shelling and the fear of aerial bombardments by the supporters of the regime, a majority of Mogadishu residents fled their homes weeks before the fall of the regime.

The author accuses all Hawiye clan members including those who she describes as “so called Hawiye moderates” as accomplices of genocide against the Darod clan. In particular, she smears former president Aden Abdulle Osman who appealed to the public on the radio. His efforts were part of larger peace efforts of Hawiye leaders to stop the mayhem of the civil war. It is unconscionable to characterize the appeal of president Adan Adde, whose wife was from Darod clan, as insincere.

Similarly, Kapteijns makes the false and mischievous accusation that General Mohamed Galal supervised the killing of soldiers in Jigjiga, Ethiopia during the 1977-78 war or that he controlled a militia of 1,500 during 1991 civil war. As reported in the memoir of Claudio Pacifico, Somalia. Ricordi di un mal d’Africa italiano, General Galal who remained loyal to the government until January 4, 1991, was forced to offer his military skill to Hawiye volunteer fighters after being attacked and chased from his home near the ministry of defense by forces affiliated with the president. The house was looted and family members were tortured.

Another Hawiye leader whose reputation was blemished in the book is Hassan Dhimbil Warsame, a lawyer, whose mother is from Darod clan. The author claims that Adv Hassan Dhimbil scolded Hawiye Militia for bringing captured Darod leaders – Abdullahi Holif, Abdulhamid Islan Farah and Abdullahi Matukade to him because he wished the militia had taken care of them i.e. killed them. The source of this fallacious story is Abdiaziz Nur Hersi, a Darod figure.

Last but not least, the author included the late Ambassador Ahmed Mohamed Darman among the Hawiye leaders accused of complicity of clan cleansing. Darman, a well-respected public servant, had deep knowledge about the events discussed in the book and lived in America but the author never attempted to contact him to ask him for more information.

The propaganda line of the author is that Hawiye leaders engaged clan cleansing to exclude the Darod clan from the patrimonial state. Two stories of the many stories reported by credible authors might shed light on the Darod’s perspective. Former US Ambassador to Somalia, Peter Bridges, in his book, Safirka: An American Envoy, recounts that small circle of Darod leaders – one of them Dr. Abyan – were meeting to discuss ways to replace Mohamed Siad Barre government with a rule that promotes Darod interests. Similarly, Michael Maren reports in his book, The Road to Hell, a story told by late Boqor Abdullahi Boqor Muse who said that late President Mohamed Siad Barre met with Harti-Darod (Majerteen, Dhulbahante and Warsangeli) leaders in 1983 and sought their support for settling half a million Ogaden-Darod in Hiiran region so that Hawadle will become a minority and Darod clan would rule the country.

Clan Cleansing in Somalia deserves collective denunciation because Lidwien Kapteijns reignites fresh recrimination among Somalis. Its conclusion is an attack on Somali culture and rapprochement. Repairing the consequences of the civil war has been addressed through several reconciliation processes that will continue through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as enshrined in the provisional constitution of Somalia. Clan politics has failed the Somali State. Somalia needs a social contract that inspires unity, justice, equality, unfailing respect of human rights and nationhood under effective national representative government.