Russia’s Energy Interests in Syria

The Syrian crisis has entered a new stage now that the regime has “won” the conflict. The main actors in this civil war are asserting their presence in various areas while continuing to battle for other parts of Syria that remain contested. Divided between Europe and Russia, the international community is thinking about rebuilding Syria’s devastated economy. But stakeholders committed to rebuilding the country continue to disagree over the means to restore the Syrian economy to its pre-war status, return millions of refugees, and bring home monies that fled to other locations, particularly the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member-states.

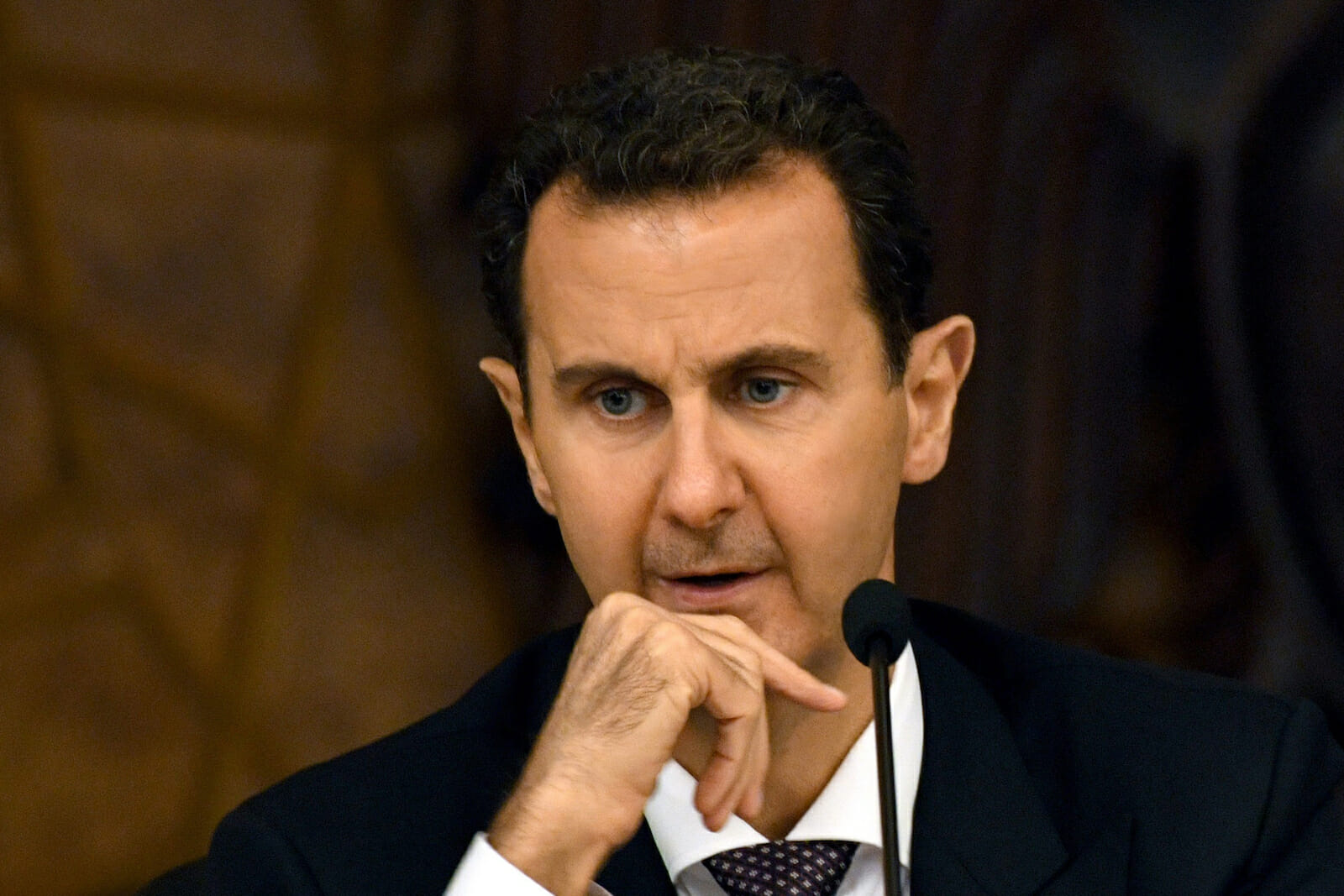

So far, President Bashar al-Assad’s regime has managed to keep the economy afloat largely thanks to credit lines from Iran. But the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign is interrupting that donation stream, resulting in acute fuel shortages in Aleppo, Damascus, and other major cities. Syria’s government-controlled domestic output declined from pre-war 380,000 b/d to 24,000 b/d.

The regime used to buy oil from the Islamic State (ISIS or IS) when its eastern provinces (Raqqa and Deir-Ez-Zor) were under the control of the so-called Caliphate. Government forces have repeatedly tried to attack these territories both from IS and later from the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). When the SDF attempted to seize these areas, the Russian Private Military Company (PMC), Wagner Group, attempted to capture the Conoco gas injection plant and the nearby oil production wells in the vicinity of Tabiyah field in Deir-Ez-Zor for the Syrian government. The Russians experienced a calamity. The Russian PMC overextended itself and ended up with almost 400 contractors being killed by U.S. forces. Russian PMCs besides Wagner such as RSB and the Russian Ministry of Defense learned a valuable lesson from this disaster.

Syria’s Contested Energy Space

Yet, Syria’s government continued buying oil from the SDF until the U.S. started to scrutinize the trade in September. Although there are still reports about local traders selling oil to regime forces in bordering areas, most of the SDF’s oil is now being transported via trucks to Kurdish parts of Iraq.

To understand the implications some background is necessary. Once an oil exporter (150,000 b/d before 2011), Syria had no choice but to ask for Iranian help. In return, Tehran provided credit lines to Damascus for its oil exports. But imports from Iran have suddenly halted this year, leaving Damascus without any alternatives to supply its almost 100,000 b/d domestic demand. One of the reasons for the interruption in supplies is growing discontent in Tehran over the unpaid credits because of the cash crisis.

Another reason is Iran’s tactic to export most of its oil to its main buyers (China and India) before the extension waivers and to implement five different methods for bypassing this stranglehold now in place by the United States. In fact, one of Iran’s tankers (True Ocean) sailed to the vicinity of Syria’s Banias port on May 5, unloading its cargo there after switching off its transponders, marking the first Iranian oil delivery to Syria since January 1. Given Iran’s economic troubles, Assad must rely on Syria’s oil-rich ally, Russia.

Enter Russia

Russian companies have historically been present in Syria’s energy industry. Stroytrangas began leading the pack in the early 2000s. Gennady Timchenko, a close friend of Vladimir Putin, owns Stroytransgaz. Close ties to the Kremlin have won Timchenko projects in every single major export pipeline project of Gazprom and others, including Yamal-Europe, Blue Stream, Nord Stream, and Turk Stream.

In Syria, Stroytransgaz completed the Jordan-Syria stretch of the Arab Gas Pipeline in 2008, extending the flow of Egyptian gas into Syria. The following year it successfully commissioned South Gas Processing Unit in Hayan, 30 miles from Homs. Commissioning of the first gas plant as well as the development of nearby gas fields by Stroytransgaz subsequently proved to be crucial in Assad’s efforts to sustain the energy security for the war economy. Development of the gas-rich Palmyra basin by Stroytransgaz in partnership with the Syrian Gas Company served to boost Syria’s gas output and consequently increase the share of natural gas in power generation that was previously run on oil. In hindsight, this development proved to be a game changer as Syria became more dependent on imported oil.

Stroytransgaz intensified its activity following Assad’s pledge to provide the preferential status to Russian companies in the energy sector of his country in 2016. The company resumed reconstruction of the second gas processing plant nearby Raqqa in 2017 while winning contracts to modernize refineries in Banias and Homs, two of Syria’s largest. More recently, Stroytransgaz signed a 50-year contract to develop the phosphate fields in Palmyra and the expansion of the port in Tartus.

Although Syria is not a formidable oil or gas player, Russia’s deepening energy interest in the country is important for the following reasons. First, Syria remains the key element of Russia’s recent pivot to the Middle East and North Africa, in which energy diplomacy plays an important role. Second, the country has promising oil and gas potential, especially, in the East Mediterranean basin, which in light of the race for the territorial waters of Lebanon, Cyprus, and Israel, has become one of the world’s most promising basins. It is especially valuable for Putin’s close friends, who have suffered the impacts of America’s sanctions. Naturally, the geographic location of the country also plays an important role for Russia. Syria borders oil-rich Iraq and is located relatively close to GCC member-states and Europe.

Syria will unquestionably need Russia on the energy front for the foreseeable future. The Kremlin naturally knows this fact. As an energy platform, Syria is necessary for the further development of energy networks that are currently in Russia’s sights. This trend line is in plain view from Greece to Cyprus, Lebanon to Israel, and Egypt to the entire Maghreb.

Economically, just as Iran is under pressure from America with robust sanctions, so is Russia. This factor binds Moscow and Damascus together in the eastern Mediterranean’s emerging energy arena. Russia’s contracts with Syria for a 49-year lease of Tartus port and open-ended use of Khmeimim Air Base enables Russia’s ability to protect and project its forces to safeguard current and emerging energy infrastructure, most of it located at sea in the Leviathan and Zohr fields in the Eastern Mediterranean. Further away, Russia, from Syria, can “hub” its way across the rest of the Mediterranean and out the Strait of Gibraltar by using a series of port and airport access agreements. From Syria, Russia can project its influence with naval and air assets in an asymmetrical way that can be used to harass or halt shipping to protect national interests under the concept of “Russian sovereignty.” But first and foremost, Russia needs to support Syria’s energy requirements.