Sergei Lavrov’s Gulf Tour: A Bellwether of U.S.-Saudi Relations

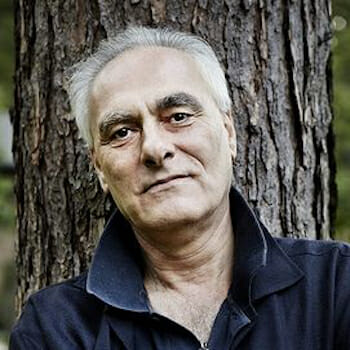

As Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov embarks on a four-day visit to the Gulf, Middle Eastern leaders are either struggling to get a grip on Joe Biden’s recalibration of U.S. policy in the region or signaling their refusal to adapt to the president’s approach.

Mr. Lavrov’s visit to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar comes a week after the United States released an intelligence report that pointed fingers at Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for allegedly ordering the 2018 killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Earlier, the United States halted the sale of weapons to the kingdom that could be deployed in its six-year-long devastating offensive in Yemen.

Even though he is not stopping in Istanbul and Jerusalem, Mr. Lavrov is traveling in the region as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is still waiting for a phone call from Mr. Biden and Israel is suggesting that it may not engage with U.S. efforts to revive the 2015 international agreement that curbed Iran’s nuclear program and could act on its own more aggressively to counter the Islamic Republic’s nuclear ambitions.

Mr. Lavrov is certain to want to capitalize on Mr. Biden’s rattling of Middle Eastern cages amid perceptions that recalibration of relations with Saudi Arabia and delayed phone calls suggest that the United States is downgrading the Middle East’s importance in its global strategy, reducing its security commitments, and potentially considering a withdrawal.

There is little doubt that the United States wants a restructuring of its commitments through greater burden-sharing and regional cooperation but is unlikely to abandon the Middle East altogether.

The question is whether Mr. Biden’s rattling of cages constitutes simply signaling U.S. intentions or a deliberate attempt to let problematic allies and partners stew in uncertainty in a bid to increase the administration’s leverage.

Potentially the longer-term strategy may be an unintended yet beneficial consequence of the administration’s conviction that addressing domestic emergencies such as the pandemic and economic crisis as well as repairing relations with America’s traditional allies in Europe and Asia is a pre-requisite for restoring U.S. influence and leverage that was damaged by former President Donald J. Trump.

If so, Mr. Lavrov may unwittingly be doing the Biden administration a favour by attempting to exploit perceived daylight between the United States and its allies to push a Russian plan for a restructured security architecture.

That plan envisions a Middle Eastern security conference modeled on the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and a regional non-aggression pact that would be guaranteed by the United States, China, Russia, and India.

In doing so, Mr. Lavrov would be preparing the ground for debate about a concept that has been discussed in different forms at various points by U.S. officials, in which a United States that credibly is getting its house in order would retain its dominant position as the military backbone of a new security architecture.

It would also drive home the point that neither Russia nor China are willing or capable of replacing the United States and that Middle Eastern countries are likely to benefit most from an architecture that allows them to diversify their relationships and potentially play one against the other.

So far, Saudi Arabia has insisted “that the partnership between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States of America is a robust and enduring partnership” even though it rejected in the same statement the U.S. intelligence report as “negative, false and unacceptable,” that MbS was culpable in Khashoggi’s murder.

For now, Saudi Arabia appears determined to counter strong winds in the White House as well as Congress rather than rush to Moscow and Beijing in a realignment of its geopolitical and security relationships.

To do so, the kingdom, in the run-up to the release of the report, has broadened its public relations and lobbying campaign to focus beyond Washington’s Beltway politics on America’s heartland where fewer people are likely to follow the grim reality of the war in Yemen, a country that the Saudi-led bombing campaign has turned into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis or the gruesome details of Mr. Khashoggi’s killing.

The campaign appears designed to create grassroots empathy for Saudi Arabia across the United States that would filter back from constituents to members of Congress.

“We recognize that Americans outside Washington are interested in developments in Saudi Arabia and many, including the business community, academic institutions, and various civil society groups, are keen on maintaining long-standing relations with the kingdom or cultivating new ones,” said Fahad Nazer, a spokesman for the Saudi embassy in Washington.

Filings show that companies lobbying on behalf of Saudi Arabia reported that half of their 2,000 lobbying contacts in the last year were with individuals and groups outside of Washington.

Working with local and regional companies outside Washington, including Larson Shannahan Slifka Group (LS2 Group) in Iowa and its subcontractors in Maine, Georgia, North Carolina, and other states, Saudi lobbyists contacted local chambers of commerce, media, women’s groups, and faith communities including synagogues.

The lobbyists distributed materials touting the benefits to women in sports and other sectors accrued from Prince Mohammed’s social reforms in a country that banned women from driving as recently as three years ago.

The Saudi focus is unlikely to deter Mr. Lavrov from peddling Russian military hardware during his tour of the Gulf, including the S-400 anti-missile defense system that Saudi Arabia expressed interest in long before the U.S. election that swept Mr. Biden into the White House.

The kingdom has so far not taken its interest any further. Whether it does so during this week’s visit by Mr. Lavrov will serve as a bellwether of whether Saudi Arabia will turn towards Russia and China in a significant way.

So far U.S. analysts appear to be unconcerned.

Said former U.S. intelligence official Paul Pillar, a frequent commentator on Middle East affairs: “The attractiveness of doing business with the United States will remain without the coddling, as is true of Saudi choices regarding arms purchases, given that their defenses have been built largely around U.S. hardware.”