Sovereignty Surrendered: Subordinating Australia’s Defence Industry

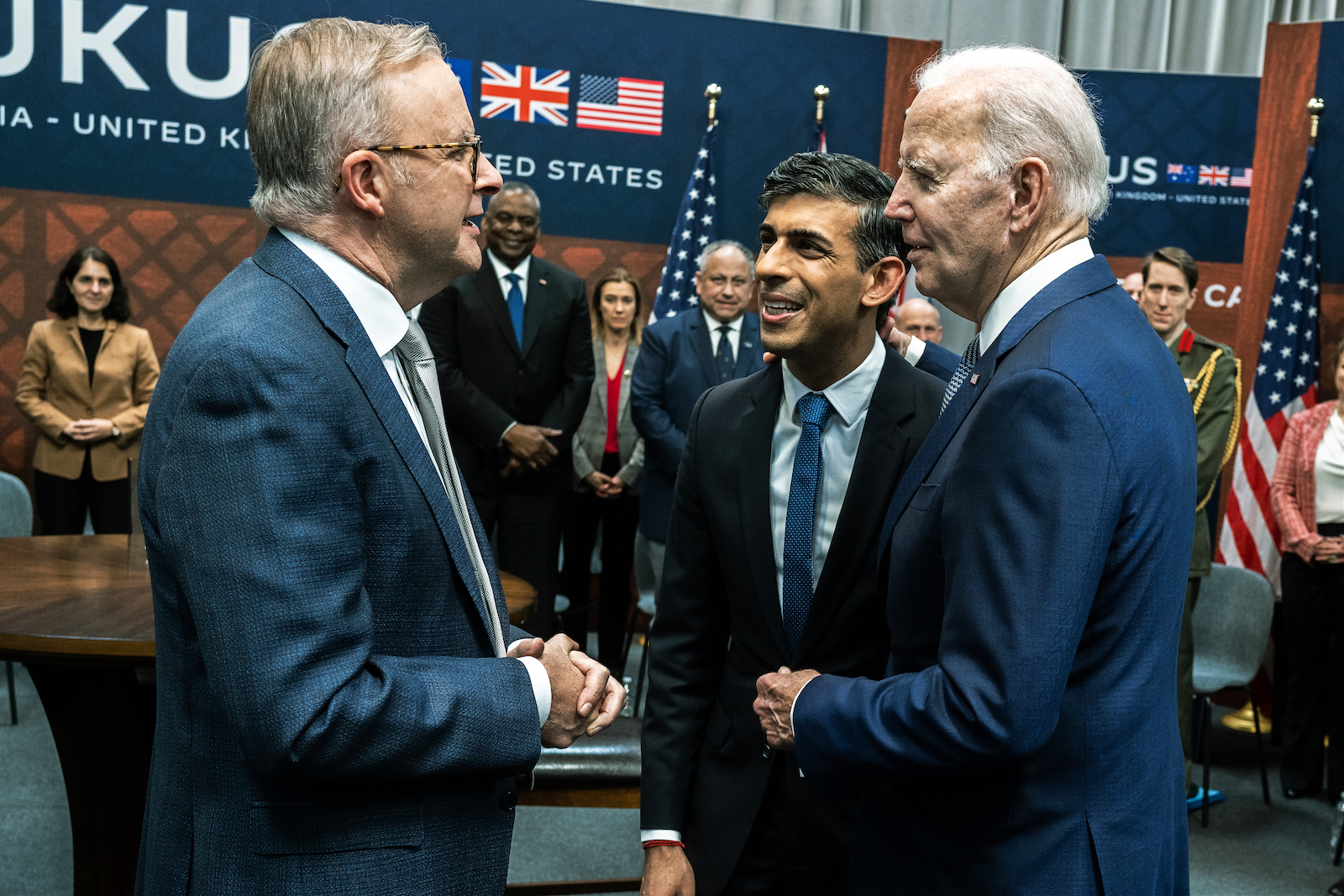

One could earn a tidy sum the number of times the word “sovereignty” has been uttered or mentioned in public statements and briefings by Anthony Albanese, the Australian prime minister.

But such sovereignty has shown itself to be counterfeit. The net of dependency and control is being increasingly tightened around Australia, be it in terms of Washington’s access to rare commodities (nickel, cobalt, lithium), the proposed and ultimately fatuous nuclear-propelled submarine fleet, and the broader militarisation and garrisoning of the country by U.S. military personnel and assets. (The latter includes the stationing of such nuclear-capable assets as B-52 bombers in the Northern Territory.)

The next notch on the belt of U.S. control has been affirmed by new proposals that will effectively make technological access to the Australian defence industry by AUKUS partners (the United States and the United Kingdom) an even easier affair than it already is. But in so doing, the intention is to restrict the supply of military and dual-use good technology from Australia to other foreign entities while privileging the concerns of the U.S. and UK. In short, control is set to be wrested from Australia.

The issue of reforming U.S. export controls, governed by the musty provisions of the U.S. International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR), was always going to be a feature of any technology transfer, notably regarding nuclear propulsion. But even before the minting of AUKUS, Canberra, and Washington had pondered the issue of industrial integration and sharing technology via such instruments as the Defense Cooperation Treaty of 2012 and Australia’s addition to the National Technology and Industrial Base in 2017.

This fundamentally failed enterprise risks being complicated further by the latest export reforms, though you would not think so, reading the guff streaming from the Australian Defence Department. A media release from Defence Minister Richard Marles tries to justify the changes by stating that “billions of dollars in investment” will be released. Bureaucratic red tape will be slashed – for the Australian Defence industry and the AUKUS partners. “Under the legislation introduced today, Australia’s existing trade controls will be expanded to regulate the supply of controlled items and provision of services in the Defence and Strategic Goods List, ensuring our cutting-edge military technologies are protected.”

Central to the reforms is the introduction of a national exemption that will cover trade of defence goods and technologies with the U.S. and UK, thereby “establishing a license-free environment for Australian industry, research, and science.” But the broader object here is unmistakably directed, less to Australian capabilities than privileged access and a relinquishing of control to the paymasters in Washington. A closer read, and it’s all got to do with those wretched white elephants of the sea: the nuclear-powered submarine.

As the Minister for Defence Industry, Pat Conroy, states, “This legislation is an important step in the Albanese government’s strategy for acquiring the state-of-the-art nuclear-powered submarines that will be key to protecting Australians and our nation’s interests.” In doing so, Conroy, Marles, and company are offering Australia’s defence base to the State Department and the Pentagon.

With a mixture of hard sobriety and alarm, a number of expert voices have voiced concern regarding the implications of these new regulations. One is Bill Greenwalt, a figure much known in the field of U.S. defence procurement, largely as a prominent drafter of its legal framework. He is unequivocal in his criticism of the U.S. approach, and the keen willingness of Australian officials to capitulate. “After years of U.S. State Department prodding, it appears that Australia signed up to the principles and specifics of the failed U.S. export control system,” Greenwalt explained to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “Whenever it cooperates with the U.S. it will surrender any sovereign capability it develops to the United States control and bureaucracy.”

The singular feature of these arrangements, Greenwalt continues to elaborate, is that Australia “got nothing except the hope that the U.S. will remove process barriers that will allow the U.S. to essentially steal and control Australian technology faster.”

In an email sent to Breaking Defense, Greenwalt was even more excoriating of the Australian effort. “It appears that the Australians adopted the U.S. export control system lock, stock, and barrel, and everything I wrote about in my USSC (U.S. Studies Center) piece in the 8 deadly sins of ITAR section will now apply to Australian innovation. I think they just put themselves back 50 years.”

The paper in question, co-authored with Tom Corben, identifies those deadly sins that risk impairing the success of AUKUS: “an outdated mindset; universality and non-materiality; extraterritoriality; anti-discrimination; transactional process compliance; knowledge taint; non-reciprocity; and unwarranted predictability.”

When such vulgar middle-management speech is decoded, much can be put down to the fact that dealing with Washington and its military-industrial complex can be an imperiling exercise. The U.S. imperium remains fixated, as Greenwalt and Corben write, with “an outdated superpower mindset” discouragingly inhibiting to its allies. What constitutes a “defence article” within such export controls is very much left to the discretion of the executive. The archaic application of extraterritoriality means that recipient countries of U.S. technology must request permission from the State Department if re-exporting to another end-user is required for any designated defence article.

The failure to reform such strictures, and the insistence that Australia make its own specific adjustments, alarms Chennupati Jagadish, president of the Australian Academy of Science. The new regulations may encourage unfettered collaboration between the U.S. and UK, “but I would require an approved permit prior to collaborating with other foreign nationals. Without it, my collaborations could see me jailed.” The bleak conclusion: “It expands Australia’s backyard to include the U.S. and UK, but it raises the fence.” Or, more accurately, it incorporates, with a stern finality, Australia as a pliable satellite in an Anglo-American arrangement whose defence arrangements are controlled by Washington.