Books

The Christian Right, Donald Trump and Religious Freedom: Q&A with Journalist Frederick Clarkson

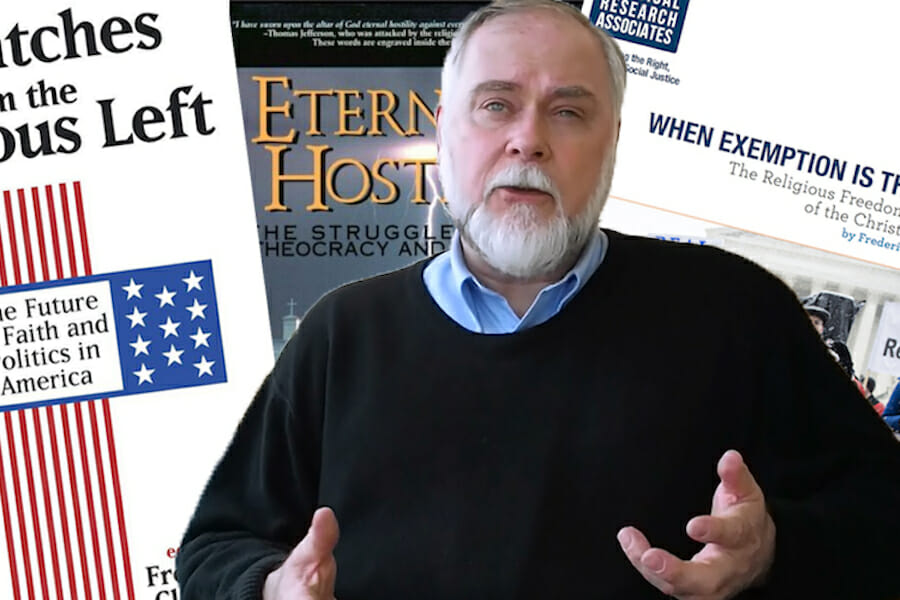

Frederick Clarkson (@FredClarkson) is an American journalist who has been writing about politics and religion for more than three decades. He now wonders how that happened. But he also says that despite the many distractions of the age of the internet, he feels like he is living in the bright light of history just about every day. He is grateful to be able to do this and remains hopeful, even on the eve of what many experience as a looming dark age.

I met Fred in the 1990’s when we were working in New York City for Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA)’s Public Policy Institute – an in-house think tank and publishing outfit whose goal was to research the organization’s criminal and political opposition, and to provide authoritative information and analysis. As a noted journalist whose beat was the Religious Right, he struck me then as a powerful source of information on the topic.

These days, he lives in Massachusetts and is Senior Fellow at Political Research Associates (PRA), a progressive social justice think tank in Somerville, MA, and is the author of the PRA report, When Exemption is the Rule: The Religious Freedom Strategy of the Christian Right.

Other publishing highlights of his career before and since PPFA include authoring Eternal Hostility: The Struggle Between Theocracy and Democracy; editing Dispatches from the Religious Left: The Future of Faith and Politics in America; and co-authoring Challenging the Christian Right: The Activist’s Handbook, for which the Institute for Alternative Journalism named him and his co-author among the “Media Heroes of 1992.”

As we were planning to do this interview, The New York Times serendipitously ran an article on the emergence of the Religious Left, on June 10, 2017. This framed much of our discussion.

“Across the country, religious leaders whose politics fall to the left of center, and who used to shun the political arena, are getting involved, the Times reported, “and even recruiting political candidates — to fight back against President Trump’s policies on immigration, health care, poverty and the environment.”

“…After 40 years in which the Christian right has dominated the influence of organized religion on American politics — souring some people on religion altogether, studies show — left-leaning faith leaders are hungry to break the right’s grip on setting the nation’s moral agenda.”

Fred, this seems to be an important development in your field. What did you think?

What’s remarkable about this piece is that it is probably the longest, most substantial article on religion and politics that has appeared in the paper in many years. Certainly on the subject of the Religious Left. Despite what I think are some important flaws, the piece has that level of gravitas that the Times brings to a major story. It is an agenda setter.

You take issue with the characterization of one person featured prominently in that story, Jim Wallis, founder and president of the evangelical Christian organization, Sojourners.

Let me say first that I have great admiration and respect for the people discussed in this report and for the reporter. But one can agree on some things and differ on others – and we do. That said, one thing that troubles me is that this story portrays Jim Wallis as a leader of the Religious Left and it appears that he has gone along with the designation. But all one has to do to find out where he stands is to Google Jim Wallis, Religious Left – the top two items feature Wallis declaring that he is not part of the Religious Left.

Obscured by casting him as religious lefty is that Wallis can in fact be called one of the architects of the Christian Right’s contemporary strategy to make abortion care less accessible by making it much more difficult to provide and to obtain.

I exposed this fact in The Public Eye magazine eight years ago. Wallis in 1996 joined a Who’s Who of the Christian Right and the anti-abortion movement, including James Dobson, Robert P. George, Beverly LaHaye, Richard Land, Frank Pavone, and Ralph Reed – in creating a document titled The America We Seek, which acknowledged that while criminalization of abortion was the goal, as a practical matter this was unlikely to happen any time soon. So until that day, they would pursue a strategy to reduce access to abortion care in the states. While he no longer calls for criminalization, the state level laws designed to radically reduce access have been passing state legislatures in record numbers for several years. To my knowledge, he is silent about that.

It is also concerning that Wallis and his framing of the Religious Left is a retread of McCarthy-era rhetoric about Godless liberals. He complained to the Times that the Left is controlled by “secular fundamentalists.” But he never identifies these people, or what exactly is secular or fundamentalist about them. He has been making this same claim for many years and had never to my knowledge, ever said who he is talking about or why, if such a problem exists, anyone should care. But his assertion plays into the historic narrative of the Religious Right.

Would you call this demonizing?

Yes.

So this inaccurate identification of Wallis as a leader of the Religious Left may call into question other points raised in the article. Would you agree?

Possibly. It suggests confusion from the beginning as to the nature and definition of the Religious Left. When my colleagues and I use the term “Religious Left,” we are not referring to a bunch of religious people who happen to be political or to political people who happen to be religious. We are talking about a possible social and political movement with a sense of common purpose, directing resources towards that purpose. The Christian Right is just such a broad movement. As for a Religious Left, the religiously based activism carried out under the rubric of resistance notwithstanding, I don’t think we quite have that yet. I am a fan of Rev. William Barber, who is profiled in the story, but which notes that he is loath to be labeled liberal or left. Well, ok. Lots of people don’t want to be confined by labels. Rev. Jennifer Butler, CEO of the Washington interest group Faith in Public Life also told the Times in a related video that she is neither left nor right but “biblical” and “scriptural.”

It seems to me it will be hard to build anything like a Religious Left, however one may define it, if people flee the label, or if the term is applied carelessly.

How would you describe or define the Christian Right? What makes the Christian Right an unprecedented social and political force?

The Christian Right is one of the most significant religious and political movements in American history. More broadly, it is arguably one of the most significant movements in the history of Christianity. And it represents a fundamental attack on the views of the Enlightenment.

It is also the result of an unprecedented rapprochement in the U.S. between conservative Catholics and evangelicals vying for leadership and control of the center of our culture and politics. They are willing to tolerate theological and political differences, to form a coherent and comprehensive alliance. This is an astounding historical development.

At Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA), we often found it difficult to discern just how organized and focused and dangerous our opponents really were. However, after a closer look at specific Christian Right entities – e.g. Concerned Woman for America, which recruited and trained evangelical women to further its radical political agenda – we understood that our opponents were indeed highly organized. Comment?

The Christian Right is indeed a well-organized and substantial movement. It’s not just an ad hoc collection of motivated actors – they are organized to seek to increase their capacity to do things. They have created a substantial body of thought, and a political and legal network that has matured over time. Despite the criminal activities of some, most of the actions of its adherents are not inexplicable nor are they clinically insane, although I realize that many view them that way.

The Christian Right has been built – with intention – as an organized social and political movement. This was led by what we call parachurch organizations operating outside of traditional denominational structures, such as Focus on the Family and Campus Crusade for Christ. Outside activist groups from Operation Rescue to the Christian Coalition were a natural outgrowth of this culture of functioning outside of churches and denominations for social and political impact. Major institutions were also created, from television and radio operations with national impact, to the founding of universities and law schools.

Although it could happen, there is nothing remotely analogous going on the Left.

The question we were tasked with during our time at PPFA was understanding who and what was this massive political and criminal operation bent on the destruction of PPFA? This project made great sense to me. If one is involved in any contest or struggle, you scout the opposition. You assess your opponents’ capacities and take into account their strengths and weaknesses and their strategy if you can learn or discern it.

The Christian Right is a powerful political force but most people to their left, continue to resist the idea that you have to study and understand it. Its prominence is a revealing moment in our history. Everybody should have a good idea of what it is and what it isn’t. There should be public debate on the subject but in order for us to have a good discussion, we rely on reporters, scholars, and activists on all sides to give us the information, framework, and vocabulary we need to do it.

What happened after your time at PPFA?

I returned to my life of freelance writing, editing and public speaking — recharged with fresh material and fresh perspectives. Among other things, I was interviewed for a Hollywood documentary on abortion called Lake of Fire. The film maker wanted people to question their views, but I think few people wanted to do that. So it probably got more good reviews than viewers.

I was already a journalist known for my work documenting the Religious Right before I came to PPFA. I have to say though, that the experience of working inside an organization on behalf of its purposes – while the organization was the target of sustained criminal and political attack – was extraordinary. It is one thing to read books and articles, and listen to speeches at conferences and such. It is quite another thing to be part of an organization that is the subject of a long-term campaign of stalkings, arson, bombings, and assassinations. It certainly focused my mind in fresh ways. In any other context, we would have been considered a target of terrorism. But for whatever deep-seated reasons, society had a difficult time acknowledging the nature of the campaign.

Working late one night at PPFA, I fielded a call from The New York Times about shootings at two clinics in Boston. Several people had been killed. It later turned out that the gunman had the phone number of a leader of the underground Army of God.

Talking with Planned Parenthood staffers around the country who were coping with violence and threats of violence taught me much, changed my life, and informed my book Eternal Hostility: The Struggle Between Theocracy and Democracy, which I began right after PPFA. The title comes from a quote by Thomas Jefferson engraved in the rotunda of the Jefferson Memorial. It reads: “I have sworn upon the altar of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

This was written at a time when Jefferson was under attack by the Christian Right of his day. They attacked his character and his religious beliefs. Some people were so riled up over the election of Jefferson that they hid their family Bibles believing that agents of Jefferson would come and seize them. This kind of hysteria has never left us, and to some degree drives our politics to this day.

The difference is that it is better organized and channeled into campaigns that build for power. And it has worked.

How and why did the Christian Right begin to devote their resources to supporting Trump?

Christian Right support for Trump has been perplexing because they have historically said they wanted candidates of good character and of religiosity. But in truth, like everyone else, they also wanted someone who could win and deliver for them. This is not always the same person.

Trump’s relationships with Christian Right and certain evangelical figures go back many years. The story of the origins has yet to be told, but at least a year out, some leaders pointed out that there were biblical figures who were said to have been less than godly, but who nevertheless carried out God’s purposes. One was the pagan king Cyrus of Babylon, who freed captive Jews and ultimately helped to build the temple in Jerusalem. Some said that Trump had the “Cyrus anointing.” This provided a justification to support Trump despite his extraordinary character flaws and sketchy history on some of their issues.

But some Christian Right leaders have yet to come around on Trump and wonder how it all has come to this.

At one point in this past election, there were 17 people running for the GOP nomination, some with some serious Christian Right credentials. So why Trump?

The lesson of history is that there are no perfect candidates. Christian Right support was deeply divided among the Republican presidential field. But some had come to believe that Trump could win and would deliver for them. And they were right.

Trump, the named author of the ghost-written Art of the Deal, is a transactional politician who some thought – correctly as it turned out –would use the tools of government to deliver on their agendas – the “right to life,” traditional marriage, school privatization, and certainly their idea of religious liberty.

And already, Trump has delivered for them in ways that the Christian Right of the past few decades could never have thought possible. From the people who populate his Cabinet and to the policies he has promulgated so far, he has delivered by far the most comprehensive Christian Right agenda in American history. Christian Right leaders are shocked by the breadth and depth of their own success.

What is “religious freedom?” How does it relate to Trump?

Religious freedom is the right of individual conscience, to believe as we will and to change our minds free from undue influence from government or from powerful religious institutions. In short, it is the right to believe differently from the rich and the powerful. It is also a necessary prerequisite to free speech and a free press – because without the right to believe as you will, free speech and free press become meaningless.

But like anything else that matters, how it is defined and who gets to define it, also matters. And that is why religious freedom is an issue today.

The Christian Right has been steadily losing in the areas of reproductive and LGBTQ rights, especially marriage equality. The selling point for Trump, (whose credentials in these areas were dubious at best from their point of view) had less to do with his stated support of traditional marriage or being “pro-life” – but the idea that he would fight for “religious liberty” as defined and framed their way.

This position had its roots in a remarkable statement by a convergence of conservative Catholic and evangelical leaders that produced a 2009 manifesto called The Manhattan Declaration. This document linked the idea of religious liberty to what they call the sanctity of life, and the dignity of traditional marriage.

There were some 150 original signers in the style of the Declaration of Independence — including 50 sitting Catholic prelates along with Christian Right leaders, such as James Dobson of Focus on the Family and Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council.

The Manhattan Declaration sought to bend our historic understandings of the idea of religious liberty to justify exemptions from the laws governing, among other things, access to abortion care and in making marriage equality a reality.

Religious liberty also became an ideological rallying point by which the religiously affiliated institutions could evade civil rights laws and the rights of college graduate assistants to do labor organizing, and even whether they were obligated to honor their pension agreements with their employees. The Christian Right is actively seeking to expand areas of law and jurisprudence in the area of religious exemptions in order to carve out the widest exemptions they can for individuals and institutions that they can while they hold out for a time when society might be organized along the lines they prescribe.

An alarming development?

Yes. To offer one example from popular culture, the recent Hollywood film Loving – set in time more than 50 years ago – explores the story of the Virginia couple prosecuted for violating the law against interracial marriage, which ultimately led the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn all laws against interracial marriage in the U.S.

Religious liberty arguments were used at the time in support of bans on interracial marriage. Had that notion of religious liberty then prevailed, we would not have had many of the advances in equality that we now have.

These issues are not so often heard in public discourse. Perhaps the New York Times article will attract new attention to these issues?

I hope so. We need a lot more such quality reporting in this area. The American experiment is premised in considerable part on our ability to function in the face of religious differences. But democratic pluralism only works when people are committed to making it so. The bitter truth is that not all of us share this aspiration. And others of us are not well equipped to defend it, and worse, some also don’t seem to think they need to be.

Do you anticipate a change in media focus on religion – perhaps an increased focus on the Religious Left?

I think so, yes. There are actual stirrings of organized efforts by religious progressives to respond more effectively in the face of the regressive politics and policies of our time. I expect that new leaders and organizations will emerge from this, and probably quite independent of religious institutions that tend to be bastions of conformity, allowing them far greater political flexibility and that defy easy categorization and conventional approaches to politics.

My 2009 anthology Dispatches from the Religious Left sought to jump-start a national conversation about these things. An authentic Religious Left, as the various writers envisioned it, could not be manufactured by liberal interest groups, PR firms, and the Democratic Party which had seemed to be attempting to do just that.

There has been nothing like a Religious Left for a very long time. What might a contemporary Religious Left look like?

No-one to my knowledge has ever set forth a list of principles of a possible Religious Left, but since you asked….

Marshall Ganz likes to use the story of Moses as a model for leadership. Ganz says people followed him because he had a big vision and a plan to get there. We put together Dispatches from the Religious Left to jump-start a conversation about these things and see what kinds of visions, leaders and plans might emerge. One of the main tasks at that time was to recognize that we were not getting such leadership from the faux Religious Left being manufactured from inside the Washington Beltway.

I think only big, bold, dynamic visions are likely to lead people not into the temptation of complacency, milque-toastery, and hopeless gestures, but towards a future of which we could all be proud. A Religious Left, then, would be a broad, well-organized, social and political movement intending, to borrow from Martin Luther King, to bend the arc of history towards justice and speak from “the fierce urgency of now.”

It would comprise people of many religious traditions, as well as the non-religious who choose to be a part. It would seek and marshal resources in pursuit of its objectives. It would have multiple sources of organizational strength; a variety of significant leaders; well considered ways of expanding that leadership as well as followership; and ways of sustaining itself over time. It would have some media, and some legal representation, of its own.

It would seek to achieve its own mission on its own terms in ways consistent with its own values. It would not ape the Religious Right and it would avoid taking the wrong lessons from its success. An authentic Religious Left would seek a broad and dynamic vision and the means to achieve it. It would need to be faithful to the best of our respective traditions and to the task of democracy itself – the idea that everybody counts.

It would certainly hold to values of reproductive justice, LGBTQ rights, religious pluralism, separation of church and state and the historic value of religious freedom. It would be religious in character and it would actually be Left.

It would be determined to head off climate change; seek broad racial and economic justice; it would seek and support strong governmental checks on the excesses of capitalism; it would seek to advance human rights and roll back unjust foreign and military policies. It would be as dynamic as the labor movement, the women’s movement, and the Civil Rights movements in their day and stand for the best of what these movements were about.

It would also have to develop a considerable electoral capacity not limited to registering voters, but also developing and electing its own politicians or at least those compatible with its values. It would need to figure out the relationship between religious identity and citizenship.

There would be plenty of room for disagreement, discussion, and debate – and the movement would not look to models from the early years of this century when, as Jeff Sharlet wrote in his afterword to Dispatches, some had sought to pass off a “centrist coalition of the willing” as a Religious Left. Factotums of the Democratic Party had sought small numbers of voters for short-term political gains – and would have been aghast if a movement had emerged that stood for anything remotely like a Religious Left worthy of the name.

I know that Dispatches generated some of the discussion we had hoped for. And it may be that this interview may be arriving at a good moment to restart that still necessary discussion.