Health

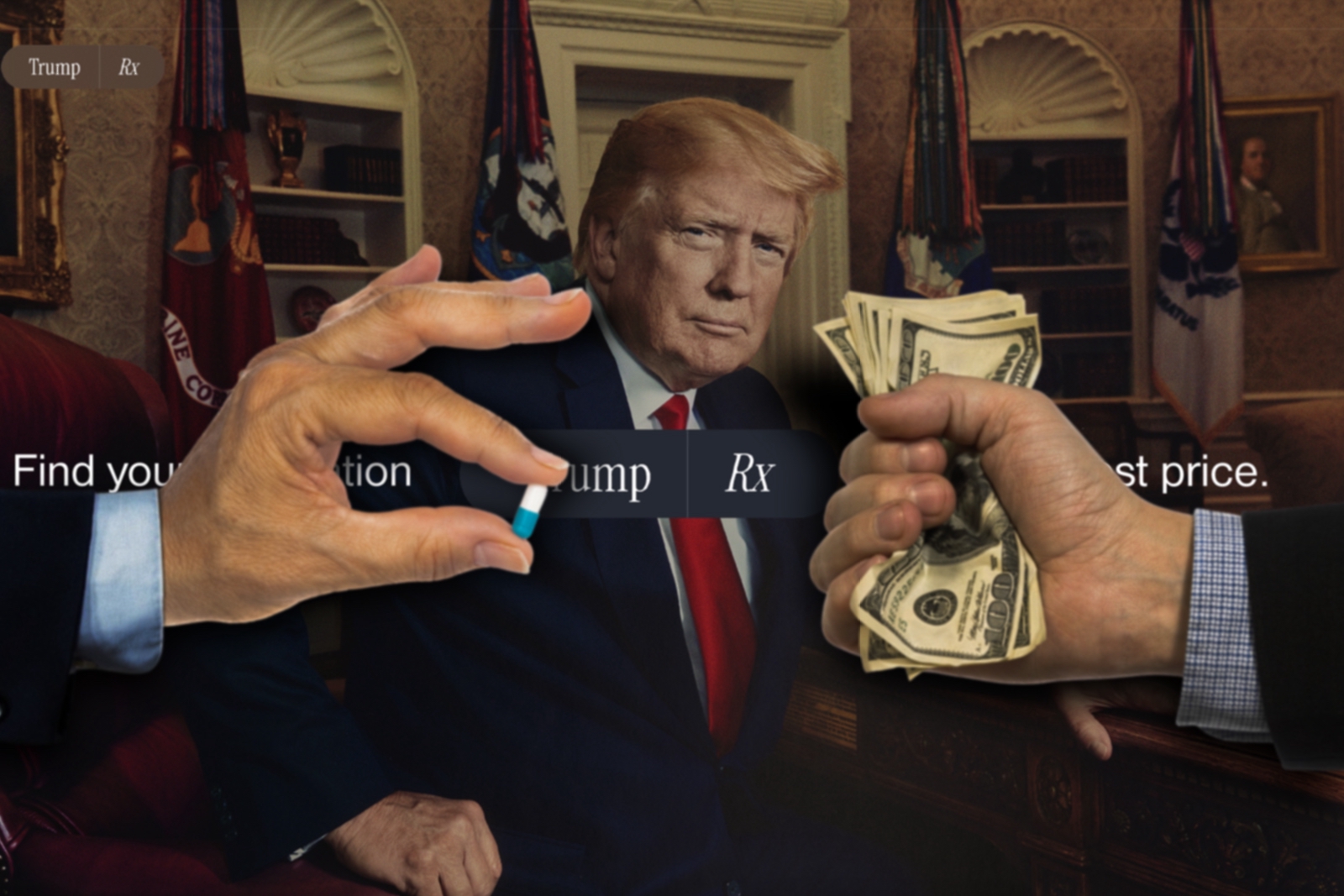

The Fine Print Behind TrumpRx’s ‘Discounts’

On the eve of the shutdown, President Trump hosted Pfizer’s CEO in the Oval Office. In what he called one of the “biggest medical announcements that [his] office has ever made,” the president heralded a prescription-drug deal with the nation’s largest pharmaceutical company.

Though the terms remain confidential, Pfizer agreed to several of the administration’s long-standing demands: discounts on select prescription drugs, significant new investment in U.S. manufacturing, and participation in the TrumpRx direct-to-consumer (DTC) platform.

The flashiest headline was TrumpRx itself—a centralized landing page where leading drugmakers can sell directly to patients.

For Pfizer and AstraZeneca, which struck a similar deal last week, the upside is obvious. On May 12, President Trump issued an executive order warning top pharmaceutical firms: adopt “Most Favored Nation” pricing to narrow the gap between what Americans and Europeans pay for the same medicines—or face 100 percent tariffs.

These concessions offer safe harbor from tariffs and from legally dubious enforcement gambits at the Department of Health and Human Services—dubious because courts struck down comparable price-setting attempts in 2020. And there’s a more immediate carrot: companies on notice are now incentivized to advertise steep discounts on certain specialty drugs if consumers buy straight from them.

Wall Street liked what it saw. In the week after the Oval Office rollout, Pfizer’s stock jumped roughly 14 percent. AbbVie, Merck, and Eli Lilly—reported to be next up for TrumpRx—rose about 10 percent. The market’s enthusiasm, however, clashes with the deep discounts being dangled to consumers who buy brand-name drugs directly from manufacturers.

Early signs suggest that Big Pharma’s warm embrace of DTC will do little for Americans’ out-of-pocket costs, especially for people who are already insured. The “Pharma-to-table” model also sits awkwardly alongside the administration’s pledge to crack down on the barrage of DTC ads across commercial breaks and TikTok feeds.

Consider eczema patients: Novartis’s brand-name Cosentyx lists a 55 percent price cut. That sounds generous—until you realize the annual bill still lands near $3,500, down from about $8,000. Xeljanz for arthritis remains roughly four times the UK list price. Forxiga, Pfizer’s drug for type 2 diabetes, looks better after a 70 percent DTC discount at about $180 a month—yet it’s still roughly quadruple what patients in Britain pay.

For these purchases, it’s not “co-pay.” It’s “you pay.”

This is the latest iteration of steering patients to the costliest options. We’ve all seen the pharmacy placard: “Your pharmacist may substitute a lower-cost generic for a brand-name prescription.” Yet Big Pharma has poured millions into brand advertising for drugs that often offer no added clinical value over “biosimilar” alternatives that physicians routinely prescribe and pharmacists dispense—saving patients real money. The industry insists DTC funnels savings to consumers, a claim pressed in ads that HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and the Food and Drug Administration have flagged as misleading.

There’s also an antitrust red flag. Under today’s prescribing system, drugmakers effectively set the price. Now, with a green light to build and operate their own DTC storefronts, they can make the product, set the price, and sell it—end-to-end. The likely outcome: you pay more, even after the splashy discounts.

Congress and the public broadly agree it’s time to tackle the anticompetitive tactics that inflate costs. It’s a rare point of alignment between President Trump and Senator Bernie Sanders, the HELP Committee’s ranking member: American patients shouldn’t be fleeced on prescription prices.

To translate that consensus into action, the White House should work with Congress to attach consequences if manufacturers refuse to offer transparent MFN pricing, as directed in the executive order. Lawmakers can fast-track the Prescription Drug Relief Act.

But that’s only a start.

Congress should also limit the number of patents drugmakers can list in the FDA’s “Orange Book,” a strategy that can delay approval of cheaper generics by 30 months. The Senate Judiciary Committee has already advanced five bipartisan bills that would curb these anticompetitive maneuvers—a key driver of high pharmacy bills.

Credit where it’s due: the Trump-era FTC continued work this year to scrutinize patent abuses. Still, officials should strengthen the carrot-and-stick approach for blockbuster manufacturers by endorsing the “sticks” Congress is ready to supply.

The sentiment behind the president’s vow to slash drug costs by “1,200, 1,300, 1,400, 1,500 percent” tracks with public frustration—even if the arithmetic doesn’t.

What should be clear in the meantime is this: Big Pharma needs to be candid in its ads and with consumers. The DTC model is not a cure for high drug prices.