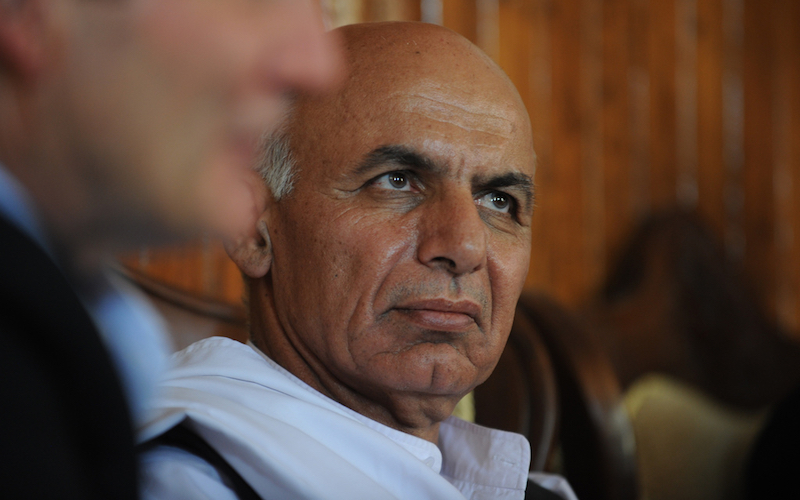

The Hazara Dilemma: Ghani in Australia

Australian government officials are at it again, and the visit by President Ashraf Ghani to Canberra on Sunday piqued interest amongst various members of the Afghan community concerned about the next innovation in cruelty practiced by Canberra.

If there is something exceptional in the otherwise dreary annals of Australian policy making in recent years, repelling unwanted refugees and asylum seekers must count high among them. Be it offshore processing, third party swaps with distant, often poorer countries, and general operational secrecy, the Australian state has been a dubious pioneer of sorts in a field where flouting the United Nations Refugee Convention has become a routine matter.

This model of muscular repulsion has received praise from European reactionaries keen to keep the standard of civilization flying high and defiant against Islam. So effective has the Fortress Australia approach been (turn boats back; Operation Sovereign Borders) that it has even led Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, to believe that Australia accepts no refugees at all.

Canberra’s policies have also encouraged such figures as President Donald Trump to create his own version of a barrier against those predatory hordes of Mexicans who supposedly sup from the cup of US freedom and finance while despoiling it.

The Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, was keeping it simple and vacuous in describing Afghanistan, essentially, as an urchin suffering growing pains, to be encouraged in programs of development rubbished by the historical record.

An agreement worth $320 million in development was duly signed between the leaders, again detracting from the greater problems Kabul faces, including its chronic inability to actually spend more than 60 percent of its annual budget. “During this visit, discussions will focus on our ongoing security and development cooperation to help Afghanistan in its efforts to become more prosperous, secure and self-reliant.”

These measures smack of illusion and delusion. For one, they presume that Ghani’s government is in control of a country in a centralised sense, pulling the levers, operating the schedules. In actual fact, much of Afghanistan remains fiercely resistant to the city centres where corruption is said to thrive, a mainly rural society in which the Taliban have buried, continuously supplying Ghani and his backers with headaches.

In January, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) conceded that the government had lost some 5 percent of its territory to the Taliban since the start of this year. Last May, the area under the control of the Afghan government had fallen to 65.6 percent, a point conspicuously ignored by partner states who have wished to keep a failing mission under wraps.

For all those logistical facts, Australia still pours money and personnel into a fantasy of development and presumed improvement, be it infrastructure projects, or Operation Highroad, featuring about 270 Australian Defence Personnel.

The word getting back to Canberra is that Ghani is doing well in his efforts, be it his promises to double the number of those in the Special Crimes Task Force, or tackle such scandals as that afflicting the Kabul Bank. The Ministry of Finance has been reformed, and corruption is being, supposedly, targeted. Reformed procurement laws from the middle of last year were deemed something of a miracle, though no formal evaluation about their success has been undertaken.

But what, ultimately, was troubling the Hazara protesters who had turned up in the mood of peaceful protest? In 2011, a memorandum of understanding was signed between Afghanistan and Australia on the subject of accepting Afghan asylum seekers who had failed to make the cut. A good number of those who have fallen into this trap are those from the Hazara group, implicitly suggesting that various persecuted minorities would be placed under a withering and unsympathetic spotlight.

“Areas of cooperation” highlighted in the Memorandum of Understanding include “activities aimed at increasing the capacity of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to develop policies and institutional arrangements that address the root causes of irregular migration, the irregular movement of people and the incidence of people smuggling.” The focus, in other words, is to emphasise local measures, with Australian insistence, rather than facilitate the safe movement of refugees from a hopeless situation.

More to the point, much of this assessment is academic for the fact that the Australian government has promised never to settle anybody arriving by boat deemed a refugee, preferring the notion of “orderly” arrivals that supposedly takes the risk out of any journey by boat. Brutally, the policy casts aside any formal, institutional recognition about status, preferring, instead, to punish individuals for their means of arrival rather than assessing their legitimate claims for protection.

One of the gathered protestors, Barat Ali Batoor, suggested that any prospect of accepting Hazara refugees otherwise rejected by the Australian authorities was not only misplaced but dangerous. Rosy assessments about Afghanistan and its supposed improvement was, to put it mildly, absurd. Protester Najeeba Wazefadost was even more explicit: “If any Hazara is sent back home, they will be killed.”

Daoud Naji of the Hazara Enlighten Movement has also noted that his countrymen can be “active citizens in Afghanistan as well, if they have access to opportunities, but they haven’t – and they have not historically.” Turnbull and his negotiating team remain resolutely deaf to that fact, and Ghani has been more than happy to capitalise. A deep pot of cash is up for grabs.