The Known Knowns of Donald Rumsfeld

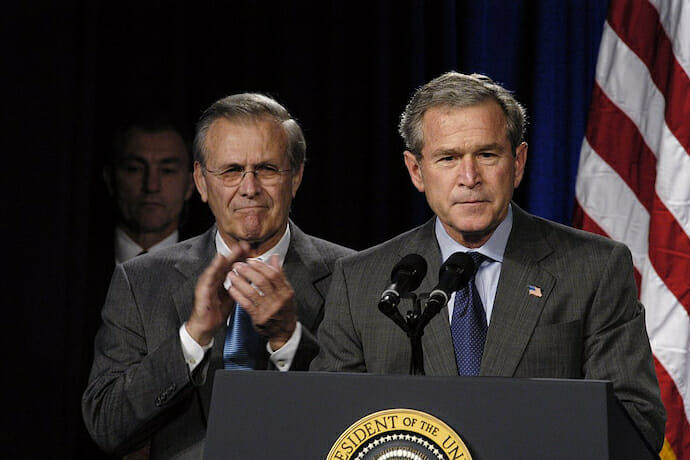

“On the morning of September 11, 2001, Donald Rumsfeld ran to the fire at the Pentagon to assist the wounded and ensure the safety of survivors,” expressed a mournful George W. Bush in a statement. “For the next five years, he was in steady service as a wartime secretary of defense – a duty he carried out with strength, skill, and honor.”

Long before Donald Trump took aim at irritating facts and dissenting eggheads, Donald Rumsfeld, two times defense secretary and key planner behind the invasion of Iraq in 2003, was doing his far from negligible bit. When asked at his confirmation hearing about what worried him most when he went to bed at night, he responded accordingly: intelligence. “The danger that we can be surprised because of a failure of imagining what might happen in the world.”

Hailing from Chicago, he remained an almost continuous feature of the Republic’s politics for decades, burying himself in the business-government matrix. He was a Congressman three times. He marked the Nixon and Ford administrations, respectively serving as head of the Office of Economic Opportunity and Defense Secretary. At 43, he was the youngest defense secretary appointee in the imperium’s history.

He returned to the role of Pentagon chief in 2001, though not before running the pharmaceutical firm G.D. Searle and making it as a Fortune 500 CEO. It was under his stewardship that the US Food and Drug Administration finally approved the controversial artificial sweetener aspartame. A report by a 1980 FDA Board of Inquiry had claimed that the drug “might induce brain tumors.” This did not phase Rumsfeld, undeterred by such fanciful notions as evidence.

With Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980, and Rumsfeld’s membership of the transition team, the revolving door could go to work. The new FDA Commissioner, Arthur Hull Hayes, Jr., was selected while Rumsfeld remained Searle’s CEO. When Searle reapplied for approval of aspartame, Hayes, as the new FDA commissioner, appointed a 5-person Scientific Commission to review the 1980 findings. When it became evident that a 3-2 outcome approving the ban was in the offing, Hayes appointed a sixth person. The deadlocked vote was broken by Hayes, who favoured aspartame.

In responding to the attacks of September 11, 2001, on US soil, Rumsfeld laid the ground for an assault on inconvenient evidence. As with aspartame, he was already certain about what he wanted. Even as smoke filled the corridors of the Pentagon, punctured by the smouldering remains of American Airlines Flight 77, Rumsfeld was already telling General Richard Myers, the vice-chairman of the Joints Chief of Staff, to find the “best info fast…judge whether good enough [to] hit SH@same time – not only UBL.” (Little effort is needed to work out that SH was Saddam Hussein and UBL Usama/Osama bin Laden.)

Experts were given a firm trouncing – what would they know? With Rumsfeld running the Pentagon, the scaremongers and ideologues took the reins, all working on the Weltanschauung summed up at that infamous press conference of February 12, 2002. When asked if there was any evidence as to whether Iraq had attempted to or was willing to supply terrorists with weapons of mass destruction, given “reports that there is no evidence of a direct link,” Rumsfeld was ready with a tongue twister. “There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” This was being frightfully disingenuous, given that the great known for Rumsfeld was the need to attack Iraq.

To that end, he authorised the creation of a unit run by Douglas Feith, the under-secretary of defense for policy, known as the Office of Special Plans, to examine intelligence on Iraq’s capabilities independently of the CIA. Lt. Colonel Karen Kwiatkowski, who served in the Pentagon’s Near East and South Asia (NESA) unit a year prior to the invasion, described the OSP’s operations in withering terms. “They’d take a little bit of intelligence, cherry-pick it, make it sound much more exciting, usually by taking it out of context, often by juxtaposition of two pieces of information that don’t belong together.”

One of Rumsfeld’s favourite assertions – that Iraq had a viable nuclear weapons program – did not match the findings behind closed doors. “Our knowledge of the Iraqi (nuclear) weapons program,” claimed a report by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “is based largely – perhaps 90% – on analysis of imprecise intelligence.”

None of this derailed the juggernaut: the US was going to war. Not that Rumsfeld was keen to emphasise his role in it. “While the president and I had many discussions about the war preparations,” he notes in his memoirs, “I do not recall him ever asking me if I thought going to war with Iraq was the right decision.”

With forces committed to both Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States found itself in the situation Rumsfeld boastfully claimed would never happen. Of this ruinously bloody fiasco, Rumsfeld was dismissive: “stuff happens.” Despite such failings, a list of words he forbade staff from using was compiled, among them “quagmire,” “resistance,” and “insurgents.” Rumsfeld, it transpired, had tried regime change on the cheap, hoping that a modest military imprint was all that was necessary. The result: the US found itself in Iraq from March 2003 to December 2011, and then again in 2013 with the rise of Islamic State. Afghanistan continues to be garrisoned, with the US scheduled to leave the savaged country by September.

The torture memo signed by Donald Rumsfeld, 12/2/02, authorizing 20-hour interrogations, removal of clothing, the use of phobias, and stress positions for up to 4 hours.

Note his handwriting at bottom: “However, I stand for 8-10 hours A day. Why is Standing limited to 4 hours” pic.twitter.com/F34zbkJ5HQ

— George Zornick (@gzornick) June 30, 2021

Rumsfeld was not merely a foe of facts that might interfere with his policy objective. Conventions and laws prohibiting torture were also sneered at. On December 2, 2002, he signed a memorandum from General Counsel William J. Haynes, II authorising the use of 20-hour interrogations, stress positions, and the use of phobias for Guantanamo Bay detainees. In handwriting scrawled at the bottom of the document, the secretary reveals why personnel should not be too soft on their quarry, as he would “stand for 8-10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours?” The results were predictably awful, and revelations of torture by US troops at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 led him to offer his resignation, which President Bush initially rejected.

By November 2006, military voices had turned against him. With the insurgency in full swing and Iraq sliding into chaos, the Army Times called for the secretary’s resignation. “Rumsfeld has lost credibility with the uniformed leadership, with the troops, with Congress and with the public at large. His strategy has failed, and his ability to lead is compromised. And although the blame for our failures in Iraq rests with the secretary, it will be the troops who bear the brunt.” Bush eventually relented.

It is interesting that so little of this was remarked upon during the Trump era, seen as a disturbing diversion from the American project. When Trump came to office, Democrats and others forgave all that came before, ignoring the manure that enriched the tree of mendacity. The administration of George W. Bush was rehabilitated.

In reflecting on his documentary on Rumsfeld, Errol Morris found himself musing like his protagonist. “He’s a mystery to me, and in many ways, he remains a mystery to me – except for the possibility that there might not be a mystery.” The interlocutor had turned into his subject.