The Opaque Pacific: Fiji’s Maritime Essential Services Centre

With China constantly being accused of insufferable secrecy and a lack of openness about security and defence arrangements among its partners in the Pacific, the shoe, when on the other foot, sits just as well. In the case of Australia, it is particularly snug. We are not exactly clear about the fine print of the AUKUS security arrangement between Canberra, Washington, and London, though we all know it involves nuclear propulsion technology for submarines.

We also know little, officially speaking, about the U.S. Pine Gap intelligence facility in central Australia, though enough work has been done for us to realise how Australia is implicated in U.S. defence – or is it offence? – strategy.

In the case of the latest developments in Fiji, Australia is now playing a murky role in funding a proposed defence facility in Lami, though Canberra is keen to eschew the military intent. While there was much fuss kicked up about the Chinese not consulting the good people of the Solomon Islands about a possible military base, the residents of Lami were certainly kept in the dark about the construction of the Maritime Essential Services Centre (MESC), with Australian money, that will be located close to their homes.

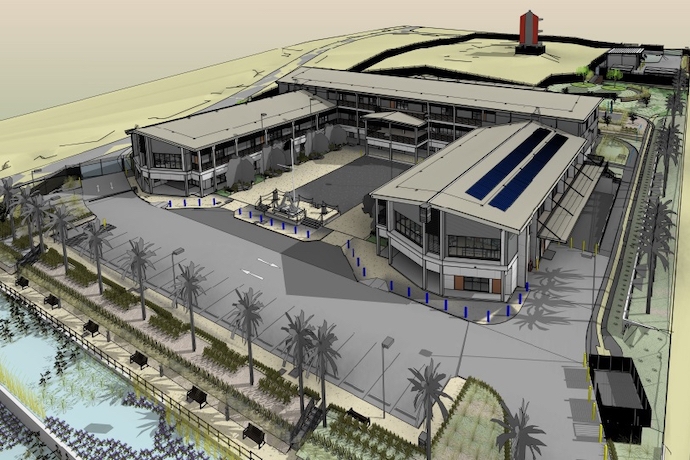

Some $57 million is going into the facility, to be located on Naimawi St. The announcement on July 14 between Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Frank Bainimarama, Fiji’s prime minister, was not exactly a noisy one. But it promised “a major infrastructure project to enhance Fiji’s maritime capabilities.” The MESC would house the country’s navy headquarters, Suva Radio Coastal Station, Fiji Maritime Surveillance Coordinator Centre, and the Fiji Hydrographic Office.

The announcement came with its usual fluffy promises: jobs for Fijian construction companies, and employment for local workers, all part of supporting the country’s COVID-19 recovery. From the Australian perspective, the measure will aid Fiji to respond “to natural disasters, protect local fishing industries, and increase naval and coastal rescue capabilities.” The Fijian prime minister, for his part, expressed “sincere gratitude to our Australian Vuvale” for ongoing support. (Albanese, for his part, droned on about the “Pacific family,” a term that labours under paternalistic suggestiveness.)

According to Bainimarama, the centre seemed to be an all-purpose one, providing a monitoring facility over Fijian waters, and would “secure our Blue Economy from internal and external threats.” It would also be part of an “expansion of our maritime protected areas in our journey towards achieving 100% ocean sustainability – just to name a few.”

Albanese’s talking points focused on Fiji’s security and prosperity, highlighting the importance of local fishing industries and the environmentally sound nature of the facility “designed to withstand natural disasters.”

The Australian Defence Department is almost at pains to sound environmentally conscious and ecologically savvy. “The design [of the MESC] is environmentally sustainable and accommodates the climatic requirements of construction in Suva, Fiji.” Apparently, it promises to be “almost self-sustaining from a water and electricity perspective with solar panels and water retention systems to be constructed.” Believe it when you see it.

On the ABC’s Pacific Beat program, local residents were asked about their views on the facility. A certain Donato, who lives and works in Lami, did not disagree with it in principle. The location was what troubled him. “In terms of an emergency or war, the problem will be the citizens could be a casualty if the naval base is targeted.” His humble view: relocate the base away from a residential zone “so it does not camouflage among the citizens of the country.”

A spokesperson from the Australian Defence Department, showing an age-old pattern in such matters, dismissed these concerns as ill-informed babble. The Lami community had been consulted – in fact, this had begun in 2019, though what exactly this involved, the spokesperson did not say. “The Fijian government is, and will remain, the lead agency for all engagement with the local Lami community.”

This would suggest little by way of engagement. The Fiji Times notes a number of consultations, but remains oblique about the level of involvement with local residents who would be directly affected by the site. The first consultation took place in July 2019, the next in December 2021, followed by a “local industry engagement forum in February.” There was also a sevusevu (a ceremonial gift as part of Fijian protocol) to the landowners in July and “further consultations in August.”

It would seem from this account that Lami residents were only briefed in greater detail at the fourth consultation session held at the Lami Parish Hall, one conducted by the Ministry of Defence, National Security and Policing. But when representatives from the Australian government and the project contractor braved a local audience in early August, the reception proved frosty.

Pertinently, questions were asked as to why the Lami siders were not consulted when plans for the proposed site were already being drafted two years ago. There were also concerns about congestion, the safety for children and grandchildren given the proximity of the site to the local primary school, and the dangers posed by construction work. Questions were also posed about the risks of property devaluation.

The Australian representatives were hardly brimming with information. The Australian High Commission preferred to answer the indignant queries by email, and even then, ignored most of them. This was all part of Australia’s wider Pacific infrastructure plan regarding maritime and land-based facilities, and the locals would do best to appreciate it. “The project is expected to generate [$24 million] in labour and construction revenue for the Fijian community.” And throw in 445 jobs.

Residents have also been told, almost condescendingly, that their site had to be chosen. The MESC could not, for instance, be built at Togalevu because of “ground integrity issues.” Nor would it be constructed on the Bilo Battery gun site, given its national heritage status. Besides, the Australian prime minister has already claimed that millions would be directly injected into the economy, and with that, the miracle of 400 jobs, though both these figures remain, at this point, astrological rather than verifiable.

Those at Lami have also been promised that no arms or ammunition will be kept at the proposed site of the MESC, though this is by no means a certainty. In the view of Fiji officials, the project was not intended to “militarise the area in any way.” This has not been exactly reassuring. With the recent ballyhoo and barking from Canberra about China’s increasingly large footprint in the Pacific, and the move by such states as the Solomon Islands to go in deeper with Beijing, those at Lami may have every right to be concerned. The temperature environmentally, and politically, is rising.