The Overlooked Reality of Jewish Refugees: A Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Shlomo Mansour is the oldest Israeli hostage in Gaza. He is among hundreds of hostages dragged across the border on October 7, 2023. No one knows if he is still alive. But what makes Shlomo unusual is that he is the only person to have survived two massacres – not just the Hamas attacks of October 7, but also the Iraqi Farhud of June 1941.

The October 7 massacre of 1,200 Israelis had all the hallmarks of the Farhud, Arabic for ‘forced dispossession’ – slaughter, mutilation, burning, looting. The Farhud, which resulted in the murder of several hundred Jews in Iraq, sounded the death knell for the 2,600-year Jewish community. Within 10 years, 95 percent had fled to Israel, fearing another Farhud.

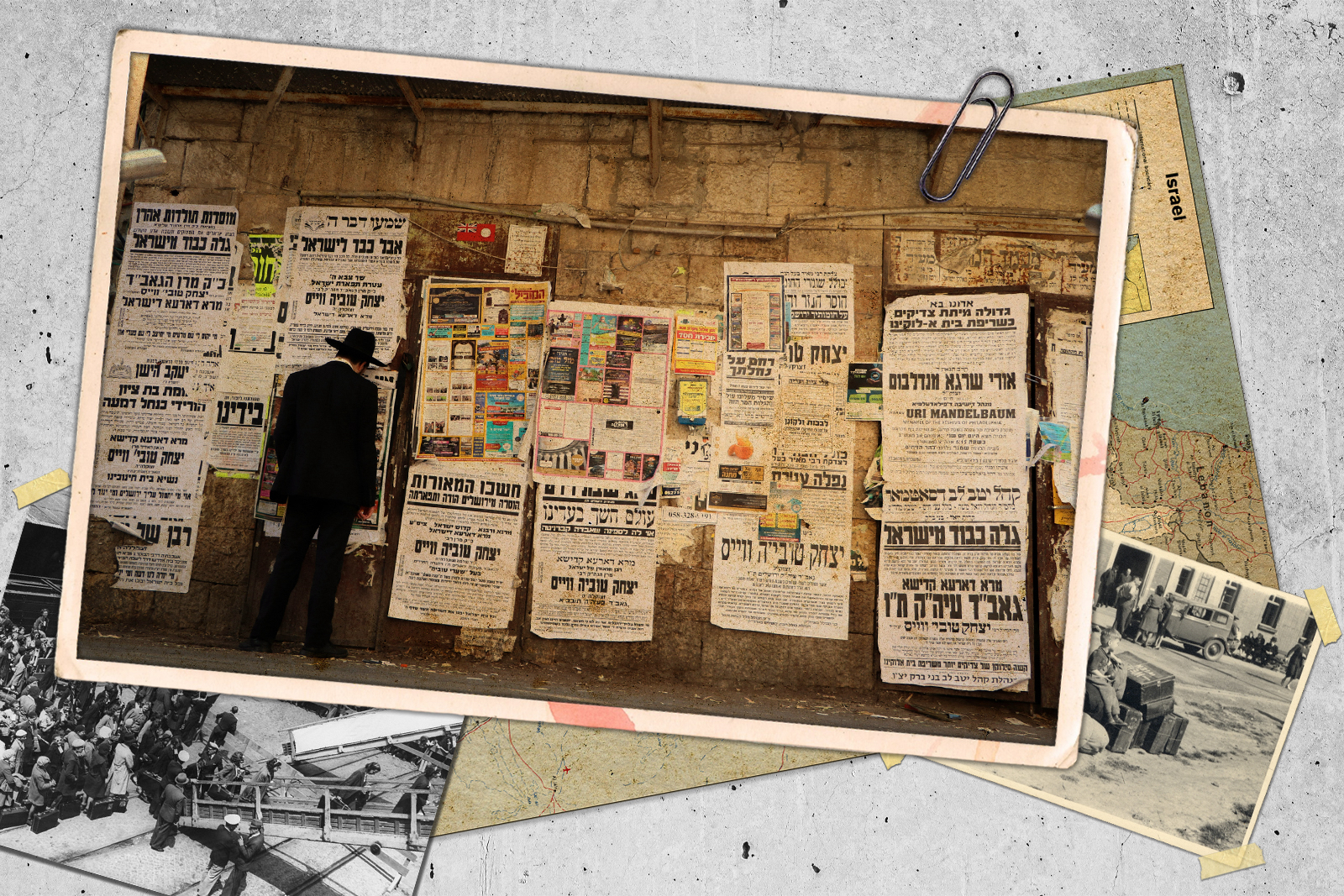

In the ongoing discourse about refugees and displaced peoples, one group is conspicuously overlooked: Jewish refugees. This omission is not merely an oversight; it represents a broader reluctance to acknowledge a complex history that disrupts the current simplified narrative often presented about the Middle East. To understand the plight of Jewish and Israeli refugees, we must first revisit history with an unflinching gaze.

For centuries, Jewish communities have been subjected to persecution, expulsion, and systemic discrimination. The Spanish Inquisition of 1492 is a prime example, where approximately 200,000 Jews were forced into exile, as was Britain’s expulsion of its Jewish community in 1290, under King Edward I. Those are but chapters in a long history of Jewish displacement, which includes the exodus of over 850,000 Jews from Arab countries in the mid-20th century. These Jewish communities faced state-sanctioned discrimination, violence, and the confiscation of property, resulting in a largely ignored refugee crisis.

This historical reality challenges the simplistic view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a mere colonial enterprise. Zionism, often misconstrued as an imperialist endeavour, is in fact a decolonisation movement by an indigenous people returning to their ancestral homeland. The Jewish connection to Israel predates many of today’s modern states, framing Zionism not as a colonial imposition, but as a reclamation of historical and cultural roots.

There’s an unsettling paradox that runs deep today, as it did yesterday: while some deny the Jewish historical connection to Israel, they simultaneously demand Jews “return home.” But where is this “home”? Historically, Jews have been expelled from numerous lands and treated as perpetual outsiders without a true homeland. This duality—of being viewed as both colonial invaders and stateless victims—reveals a deeper inconsistency in the discourse surrounding Jewish identity and rights.

The insistence that Jews must belong elsewhere while denying their historical ties to Israel perpetuates a dangerous narrative. It dismisses the legitimate claims of Jewish history and identity, ignoring the cultural and spiritual bonds that anchor Jews to Israel, and in one smooth flick of the hand, justifies pogroms and grand expulsions without, of course, accepting that there could be such a thing—a Jewish refugee, that is. This narrative is not only incoherent but also harmful, not to mention replete with antisemitism.

Contemporary Realities: The New Exodus

Today, Jewish and Israeli refugees continue to face new forms of displacement and destitution. The relentless barrage of missiles and drones from Hamas and Hezbollah, both proxies of the Islamic Republic, has forced approximately 200,000 Israelis to flee their homes. The Israeli government has mandated evacuations from 105 communities near these borders, with around 120,000 residents currently receiving aid from the National Emergency Management Authority.

This includes those from Kiryat Shmona and other threatened areas, now under missile and drone attacks. The influx of evacuees has overwhelmed hotel capacities across the country – of that, few lines or commentaries have pierced through the thick fog of antisemitism, and more to the point, the accepted notion that Jews don’t matter – only to quote foremost novelist and thinker, David Badiel.

The international community often overlooks the plight of these Israeli refugees, choosing instead to focus exclusively on other narratives. This selective empathy not only skews public perception but also perpetuates a dangerous double standard. The principle of humanitarian aid must be universal, extending to all who are displaced or in danger, regardless of their nationality or the political complexities involved.

The issue of Jewish refugees, both historical and contemporary, deserves recognition and understanding. This acknowledgment is not just about setting the historical record straight; it is about ensuring that humanitarian principles are applied equitably.

The international community must recognise that the story of Jewish refugees is integral to the broader refugee discourse. It is a story that demands justice, empathy, and a commitment to truth. As such, we cannot allow this narrative to be sidelined or misrepresented. The experiences of Jewish and Israeli refugees must be included in our understanding of global displacement, ensuring that our compassion and support are truly universal.