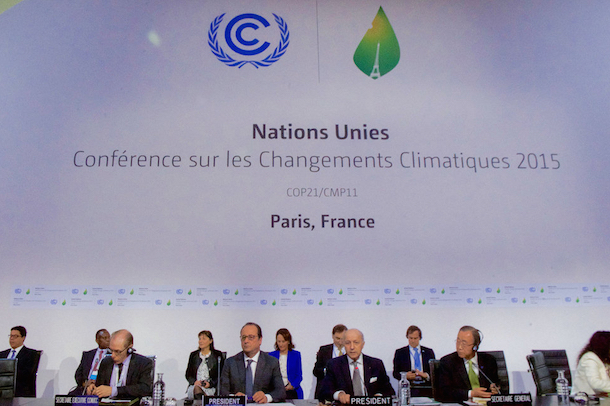

The Paris Climate Change Agreement is a Huge Disappointment

Now that the handshakes, back slapping and self-congratulatory addresses are over, the cold hard reality of what wasn’t achieved at the Paris Climate Change Conference is setting in. The delegates are to be congratulated for agreeing to anything, really, since so many previous attempts at doing so have failed, but the bar has not been set high enough, and the enforcement mechanisms are not strong enough, to warrant the praise they are heaping upon themselves. It’s almost as if having agreed to anything is worthy of congratulations. Moreover, because there really is no way to enforce what has been agreed, we must ask ourselves how much will have been achieved when we look into the rear view mirror 10 or 20 years from now.

The major components of the Agreement are:

- To limit the rise in average global temperatures to “well below” 2 degrees centigrade, while calling for “efforts” to limit the rise to 1.5 degrees centigrade. This is stronger than many countries had hoped for in the months preceding the conference, but falls short of the desires of the most vulnerable nations, which had pushed for a 1.5 degree absolute limit.

- Arriving at a peak for global greenhouse gas emissions “as soon as possible” in order to achieve “balance” in the second half of the century. The objective is to reach net-zero emissions after 2050, though the there is no specific timeline for achieving that.

- A two-stage process to ambitiously reduce emissions over time, which acknowledges that the current provisions will be insufficient to reach the long-term 2 degree maximum temperature limit. In 2018, there will be a dialogue to review the countries’ collective efforts and make future commitments. Those countries that have submitted targets for 2025 are encouraged to return in 2020 with a new target, while those with 2030 targets are invited to consider their progress. This process is supposed to be repeated every five years (i.e. rinse and repeat).

- A legal obligation on developed countries to continue to provide climate finance to developing countries, while encouraging other countries to provide support voluntarily. This includes the provision that, prior to 2025, countries should collectively agree to a floor of $100 billion per year. The idea of including short-term collective goals was cut from the text, and there is no mention of mechanisms for how the aid is to be delivered, or how to avoid theft and corruption from governments receiving the aid.

- Bind the parties to prepare and regularly update climate commitments, with each subsequent pledge intended to be more ambitious, and with developing countries being “encouraged” to move towards stricter goals. Countries would be required to “pursue…policies…with the aim of achieving” their climate pledges, while “inviting” countries to strive to achieve long-term low-emissions strategies by 2020.

- Liability and compensation as a result of loss and damages are explicitly excluded.

- A “facilitative, non-intrusive, non-punitive” system of review will track countries’ progress.

- The voluntary use of “international transferred mitigation outcomes”(i.e. emissions trading), with provisos including “environmental integrity” and no double counting. The text does not mention international aviation or shipping emissions.

In short, much of the text of the Agreement is deliberately vague, subject to interpretation, and non-binding. Many of the goals are simply aspirational. The delegates delicately danced around the most sensitive issues, such as strict requirements for adhering to the provisions of the Agreement, penalties for countries that do not comply, and a meaningful inspection regime.

While the ‘ratchet up’ provision of the Agreement looks good on paper, in that the participating countries must declare every five years what they are actually doing to battle climate change, the gap between what is actually currently being done and what these nations are ‘supposed’ to be doing in the future is huge.

There is nothing in the Agreement that requires countries to actually make greater efforts. And while the Agreement is technically ‘legally binding,’ any participating country may withdraw from it without consequence, as Canada did from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement does not require wealthy counties to achieve specific targets for cutting their own emissions. Although President Hollande immediately declared his intention to cut France’s existing carbon reduction targets before 2020, few other developed countries followed in his footsteps, as most of them are having a difficult enough time trying to meet their existing obligations.

Then there is the question of funding. With so many developed and newly industrialized countries either in recession or heading that way, and with so many national legislatures loathe to commit to spending large sums of money they do not have and do not expect to have in the longer term, developing countries’ objective of achieving a binding commitment to receive a minimum of $100 billion per year by 2020 fell flat. The Agreement suggests that developed countries should set such a goal to commence by 2025. Let’s see if that happens. I wouldn’t bet on it.

Nothing would give me more pleasure than to be able to say that the Paris Agreement was the grand achievement that its most high profile delegates seem to think it was. Perhaps achieving anything like this Agreement in this era of political, economic and social turmoil is indeed an achievement. With 195 countries sitting around the table, this is, realistically, the most that could be hoped for, but, given the collective costs implied over time, it is a sad statement that the countries did not demand more of themselves.

I also find myself wondering why any time limit was set on getting to the finish line. Instead of two weeks, if it took two months or two years, what would have been wrong with that? The Iran Agreement, with a much less ambitious agenda, took many months of sustained discussion to achieve, among 6 nations. What will the world’s leaders be saying of the Paris Agreement in a decade or two if some of the scientists are right, and we are heading toward a 3 or 4 degree average global temperature rise by 2050?

The Agreement will become open for ratification and signature in April 2016 and will only come into force if a minimum of 55 countries, accounting for at least 55% of global emissions, have ratified it. This may prove to be a tall order. Six months from now we will know whether the Paris Agreement will even be ratified. Let us also not forget that the Kyoto Protocol – the last time such an international agreement on climate change was adopted, nearly 20 years ago –was at the time hailed as a dramatic turning point. Today, most regard it as a failure. I suspect that 20 years from now, or perhaps even sooner, we will be saying the same thing about Paris.