The Platform

Latest Articles

by Manish Rai

by Sundus Safeer

by Gordon Feller

by Theo Casablanca

by Peter Marko Tase

by Abdul Mussawer Safi

by Ifaz Ali Khan

by Sohail Mahmood

by Suraj Shah

by Raisa Anan Mustakin

by Manish Rai

by Sundus Safeer

by Gordon Feller

by Theo Casablanca

by Peter Marko Tase

by Abdul Mussawer Safi

by Ifaz Ali Khan

by Sohail Mahmood

by Suraj Shah

by Raisa Anan Mustakin

Radio Free Europe’s Fading Signal—and the Fight to Keep It Alive

RFE/RL is squeezed by Central Asian crackdowns and U.S. politicization, exposing a leadership-field gap even as it keeps broadcasting when other channels go dark.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty was built for moments like this—when information is both weapon and shield, when officials demand order and citizens look for light. From the Kyrgyz highlands to the avenues of Almaty, its reporters chase stories that rarely crack the global news cycle. When the signal weakens—when someone tries to jam it—the drama turns procedural: blockades, lawsuits, accreditation fights, and the relentless accusation of bias. The plotline is familiar, but the stakes keep climbing.

In Kyrgyzstan, Radio Azattyk—the local RFE/RL service—has endured a steady constriction that looks less like a single crackdown than a tightening vise. In October 2024, authorities blocked the outlet’s website after it reported alleged election irregularities. A month later, the Ministry of Culture, Information, and Tourism revoked Azattyk’s FM license, citing non-compliance with national content standards. Reporters described intimidation and denials of accreditation that blunted routine newsgathering. Human-rights advocates called the measures a direct hit on independent media; officials answered with the language of legality and “standards,” insisting the moves were housekeeping, not censorship.

In Kazakhstan, pressure takes a bureaucratic form rather than overt force. Denials of accreditation have become part of the journalistic routine. Radio Azattyk views these steps as obstacles to independent journalism. The result is the same: the flow of information slows down.

Pressure isn’t confined to post-Soviet space. In the United States during President Donald Trump’s second term, federally funded outlets—including RFE/RL and Voice of America—were pulled into a domestic political fight. In March, Trump signed an executive order reorganizing the U.S. Agency for Global Media, accusing it of bias. The shake-up resulted in suspended grants, staff reductions, and program limitations. Courts partially blocked the measures in April, yet appellate rulings allowed temporary funding freezes. What was once a bipartisan, Cold War-era consensus about broadcasting into closed spaces turned into a live-wire debate over whether taxpayer-funded journalism has drifted from its mandate—or whether it’s being kneecapped for doing that mandate too well.

The critique from the right has been blunt. Trump has cast USAGM and its networks as hostile to his agenda, calling VOA “the voice of the Soviet Union” and “disgusting toward our country,” alleging an “anti-American, radical agenda.” Republicans in Congress pressed for budget cuts, citing left-leaning bias, prejudice against conservatives, and waste of public money on “anti-American propaganda.” Kari Lake, special advisor to USAGM, described the agency as “rotten to the core,” citing corruption, incompetence, and lax security; her house-cleaning precipitated layoffs and program suspensions. Supporters call the purge overdue, necessary to break ideological capture and refocus the mission. Critics counter that the cure is worse than the disease: you don’t save a broadcaster by turning down its volume.

Audience trust sits at the center of this fight. In Central Asia, RFE/RL’s reporting is sometimes criticized as too hard on local governments, a stance that can erode confidence among portions of the public. Its U.S. funding—integral to its identity since the Cold War—sustains perennial debates about ideological tilt. The outlet’s defense is simpler: where censorship is thick and access to facts is limited, provide verifiable information and let audiences decide. That pitch works best when the journalism feels locally grounded and insulated from political whiplash in Washington.

The work itself is precarious. Azattyk journalists in Central Asia face legal cases, blocked access, and chronic accreditation hurdles that turn basic reporting into an obstacle course. Regional economics—high household debt, fragile media markets—make independent outlets particularly vulnerable to pressure. Inside RFE/RL, critics allege opaque funding allocations and favoritism toward loyal staff, even as field reporters absorb the sharpest state pushback. These are the mundane realities of a mission-driven institution under stress: people are asked to do more with less, often while looking over their shoulders.

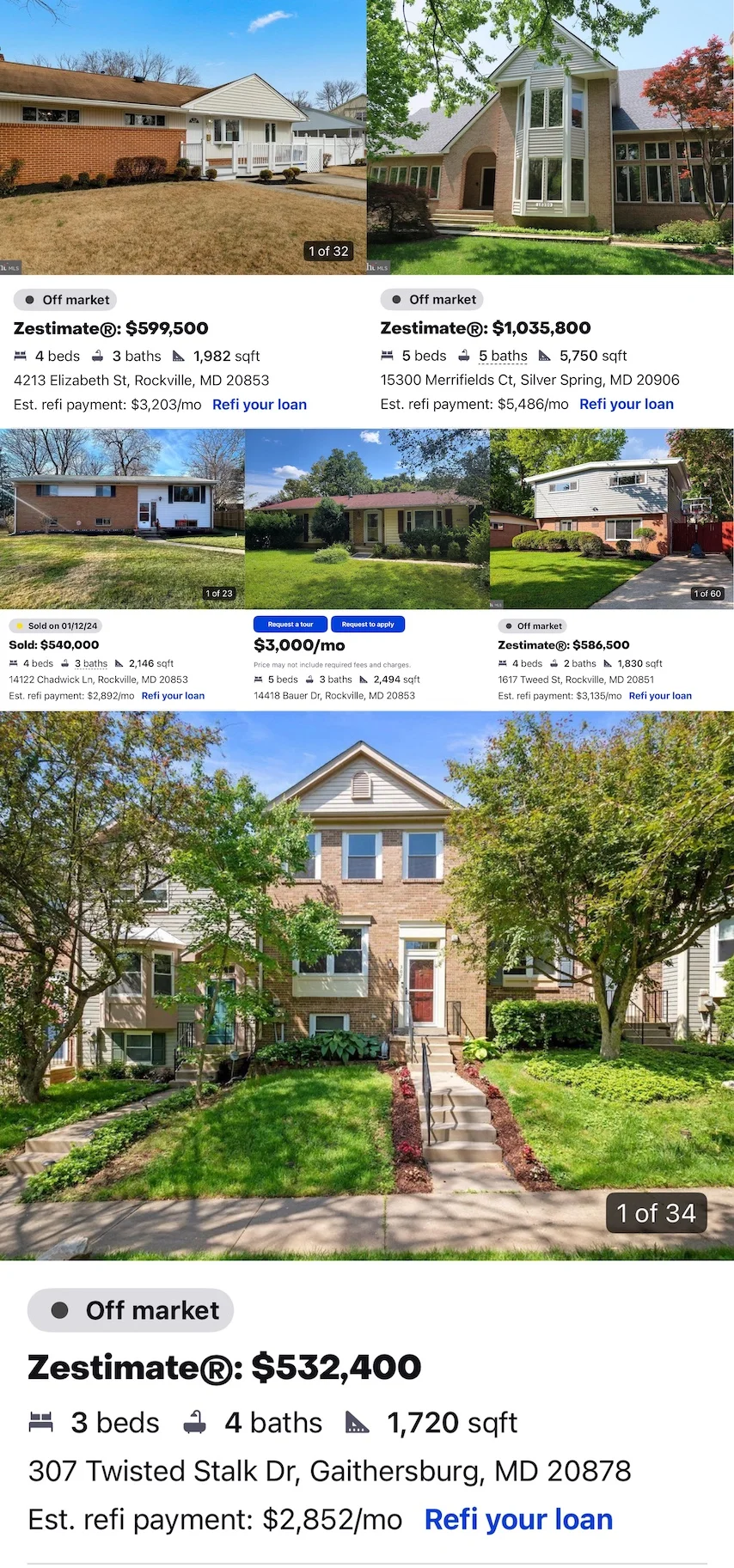

That strain reveals a leadership–field divide. Former and current executives have built stable lives far from the front-line pressures their reporters face, with property portfolios to match. Edige Magauin, former head of Azattyk’s Kazakh-language desk in Prague, is described as owning two homes in the United States (including one in a Washington suburb), a house in Prague, property in Turkey, and an apartment in Karlovy Vary. Another executive, Torokul Doorov, owns a luxury apartment in central Prague valued at around half a million dollars. Former editor Galym Bokash bought a house in Prague and now lives in the U.S. Kasym Amanzhol, Azattyk’s editor-in-chief in Kazakhstan, owns a home near Almaty. The point is not envy; it’s distance. While leadership enjoys stability, field reporters contend with risk, instability, and administrative pressure. A broadcaster celebrated for courage abroad can feel curiously insulated at the center.

And yet, the signal endures. RFE/RL persists because audiences tune in when other channels go dark. Picture a correspondent in a small Central Asian town, recording a voice note in a borrowed car as police linger nearby, while in Prague or Washington, an editor writes a headline that will travel thousands of miles. The machinery is imperfect. The mission still matters. Whether the signal can ride out the noise—censorship, distrust, and political interference—remains an open question. Perhaps the future lies in finding a more resonant voice, from Bishkek to Washington. For now, the dial continues to turn.

Theo Casablanca is a blogger who lives in Brasília.