The Problem isn’t Wealth, but How It’s Accumulated

Earlier this year, the very well-meaning but economically uninformed Nabil Ahmed, director of economic justice at Oxfam America, said the following: “During the pandemic alone, billionaires involved in the food and agribusiness sectors — just those billionaires — increased their wealth by at least $400 billion.”

The pandemic caused shortages and shortages increased prices. It’s Econ 101; if demand remains high while supply is reduced — for any reason — prices will go up. Of course, this also means the costs for those evil billionaires also went up — and by billionaires, it really means all shareholders of food-related stocks — no matter how modest their income.

Prices went up across the board, which means each dollar purchased less — including those held by billionaires. Food prices increased in cost but so did labour, fertilizer, machinery, and gasoline. What Nabil Ahmed didn’t say was that while dollar holdings increased, the value of each dollar decreased.

It should also be noted the pandemic was only responsible for part of this increase in costs — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drove up the price of food as Ukraine is one of the world’s top agricultural exporters. Russian war crimes increased the price of food for everyone making Russia a danger to increased hunger in the developing world.

In Zimbabwe, under the misrule of Mugabe, and during the Weimar Republic in Germany, hyperinflation meant the value of currencies dropped. In Germany, children made kites out of money while their mothers burned Reichsmarks in the fireplace to heat their homes as wood was worth more. In both cases, the cash holdings of people dramatically increased, with the average worker suddenly becoming a millionaire, but the value of their cash declined in real terms.

Many people are obsessed with the idea that income inequality is automatically a bad thing. They believe it is proof of the evils of the free market. Of course, there are many reasons for inequality, but they lump them all together. One business may be better run and by satisfying the needs of a greater number of consumers reaps higher income. Another may be mismanaged and have a lower income. Some people have higher incomes because they work harder while some work as little as they can get away with.

It is also true equality of income does not mean increased well-being for the people. Sutirtha Bagchi and Jan Švejnar point out in “Billionaires and Growth” the obvious, but often forgotten fact “that typical living standards are more a product of per capita income than of the degree of inequality.” They point out that Pakistan is “one of the most egalitarian economies in the world” but its equality is in a state of poverty and deprivation.

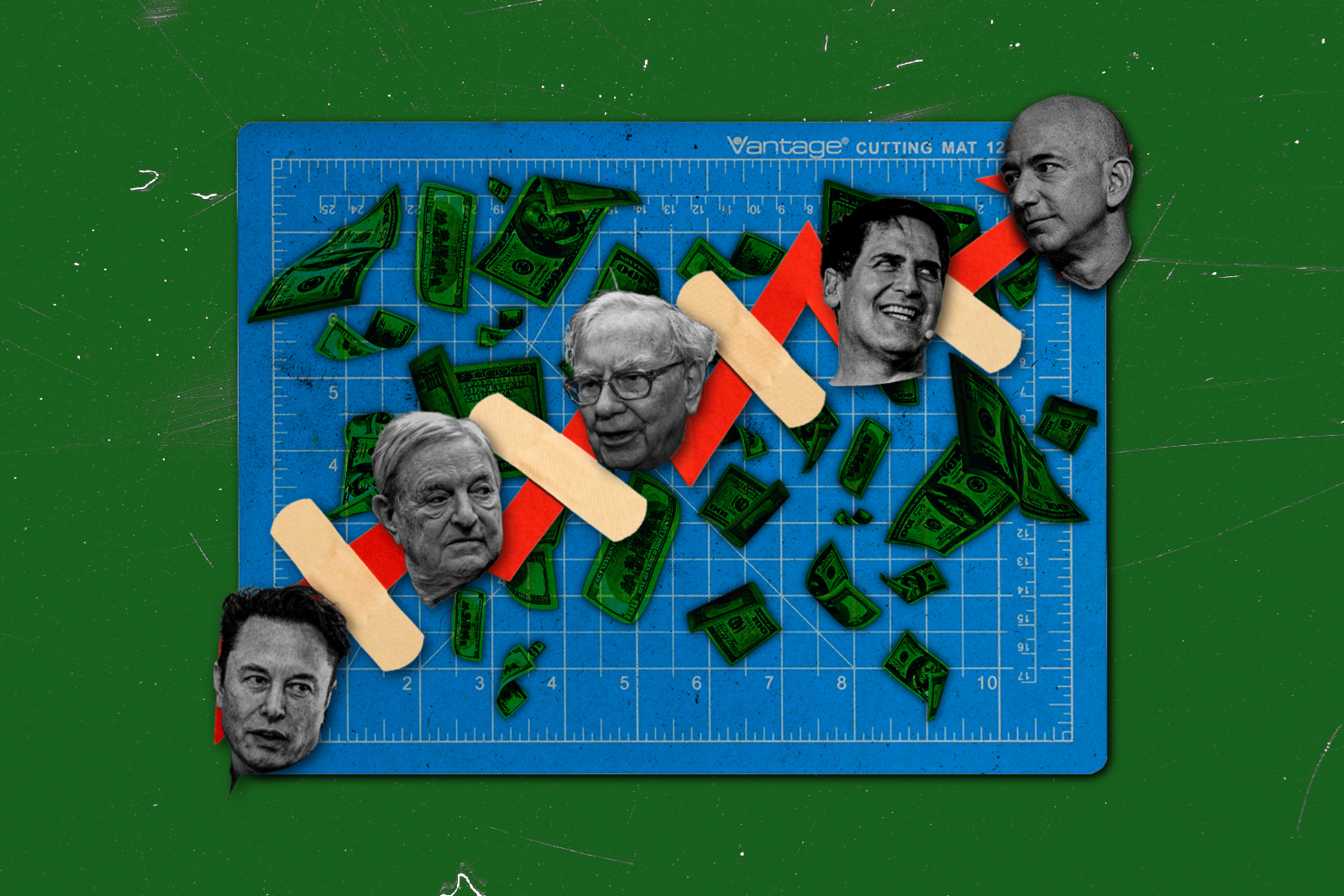

The key to discerning whether income inequality is a good or bad thing is how inequality came about, not whether it came about — as Nabil Ahmed seems to believe. Švejnar points out that billionaires — which is a general term here for the very well-off — come in two types: “[T]hose who would not have made it without political connections (i.e. political cronies), and those who became billionaires because of their ingenuity, ability to innovate and willingness to take risks (i.e. the politically unconnected).”

He points out that cronyism is found in all countries but in the Northern Hemisphere, it is concentrated in former Eastern Bloc countries and is especially rampant in Russia. ‘Crony capitalists’ in particular have a negative impact on the economy: “We discovered that billionaire wealth that arises from being politically connected has a strongly negative effect on growth. In contrast, the effect of politically unconnected billionaire wealth on the overall economy is indistinguishable from zero. That means that billionaire cronies constrain economic growth, while billionaires who aren’t cronies on average don’t do so.”

In the Washington Post, Ana Swanson notes, “[W]ealth inequality that came from political connections was responsible for nearly all the negative effect on economic growth that the researchers had observed from wealth inequality overall.”

Bagchi was quoted saying, “The negative effects of wealth inequality are largely being driven by politically connected wealth inequality. That seems to be the primary channel that drives this relationship.”

In other words, the presence of wealthy individuals can be either good or bad for the economy depending on how their wealth is accumulated. There is a world of difference between wealth creation in a free market and the use of political connections such as those that plague Vladimir Putin’s corrupt regime.

This brings us back to Oxfam which has thrown out all the nuance and data to announce “billionaires are bad for the economy.” For them, it’s a condemnation of all of them regardless if they were corrupt oligarchs in Russia plundering the people through political connections, or innovative entrepreneurs in the free society creating new wealth where before there was none.