The Return of Backyard Power Politics

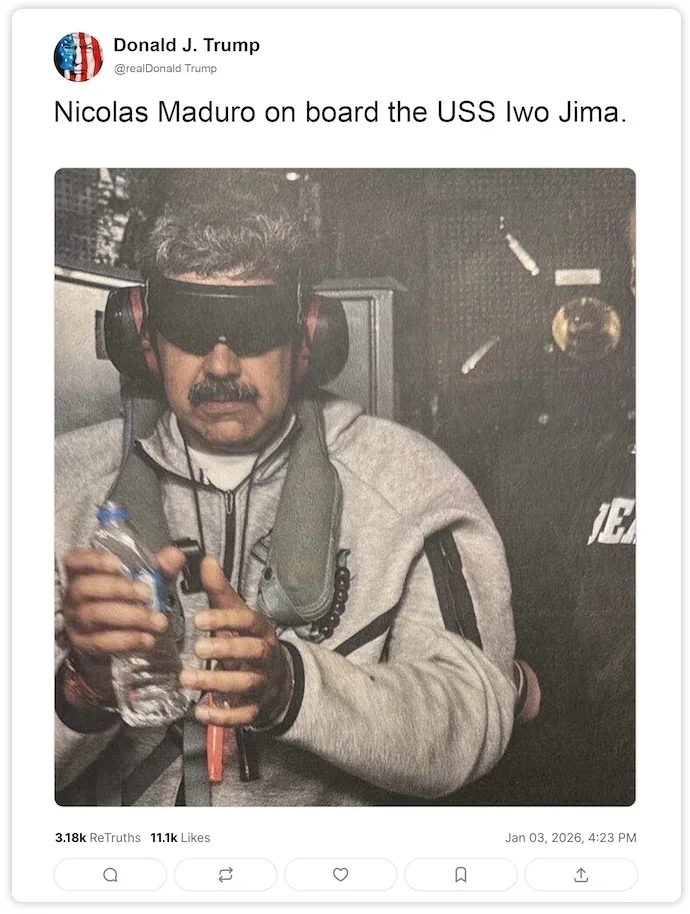

The forcible removal and kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro from Venezuela is the clearest signal yet that global politics has entered a familiar but newly sharpened phase. We are, in effect, being taken back to the future.

“Control your backyard” has re-emerged as the dominant framework of foreign policy. It is a return to great-power spheres of influence, echoing both the 1945 Yalta Conference that carved up postwar Europe and the nineteenth-century Monroe Doctrine, which Donald Trump has rechristened the “Donroe Doctrine.” The language may be modern, but the logic is old.

The era in which international law and multilateral institutions meaningfully constrained great powers, insofar as it ever truly existed, is now over. Institutions such as the United Nations were never neutral. They were designed by, and for, the dominant powers of their time. Yet where great powers once sought legitimacy through these bodies, they now increasingly bypass or ignore them altogether.

The more pressing question is not whether spheres of influence are returning, but what follows from their return. The long-term consequences may be less about borders and more about capabilities. We should be thinking in terms of spheres of expertise: who controls the world’s economic and natural resources, its digital technologies, and the architecture of the customer economy. This, rather than territorial conquest alone, is likely to define the next phase of global power.

In traditional realist theory, a state’s ability to shape its immediate neighbourhood is the foundation of its security. Rather than projecting limitless global reach, states prioritise consolidating political, economic, and technological influence close to home.

This logic is now visible across multiple theatres. The United States is refocusing on Latin America. Russia is prosecuting a grinding war in Ukraine. Israel is confronting Iran. China is tightening pressure on Taiwan. Each case reflects a similar instinct: secure what lies closest before reaching farther afield.

This approach is often described as “concentric security.” It is not about building expansionist empires, but about stabilising zones of dominance. Global engagement remains selective, but it is driven by strategic containment rather than isolationism. In today’s world, a great power’s backyard extends beyond geography to include digital sovereignty and supply chains. Control is exercised through networks as much as territory.

The United States has long treated Latin America as its backyard. From the Monroe Doctrine’s 1823 warning against European interference to late twentieth-century interventions in Panama and Grenada, Washington asserted primacy across the hemisphere with varying degrees of subtlety and success.

In recent decades, however, American attention drifted. Consumed by prolonged wars in the Middle East and distracted by the so-called pivot to Asia, Washington allowed China and Russia to deepen their footholds throughout the region.

That era has now ended. The Trump administration’s latest national security strategy makes clear that securing the Western Hemisphere is once again viewed as a precondition for American global power. Venezuela has become the test case.

With the world’s largest proven oil reserves and deep Russian and Chinese involvement, Venezuela is a prize worth contesting. Beijing, in particular, has invested heavily in Caracas. China accounts for roughly 80 percent of Venezuela’s crude oil exports and has provided more loans, grants, and weapons than any other external actor.

Yet China’s response to Maduro’s capture has been telling. As with Iran, Xi Jinping has stopped short of anything beyond rhetorical condemnation. In a contest defined by backyards, distance still matters. Venezuela may be useful to China, but it is not worth a direct confrontation with the United States in its own hemisphere.

Cuba, Mexico, Colombia, and even Greenland have all been put on notice. Trump’s evident delight in the reach of American military power risks sliding into hubris, and hubris has a habit of producing instability far beyond its intended targets.

Much commentary has suggested that Washington’s actions will embolden Russia and China into greater expansionism. This misunderstands the trajectory of both powers.

Russia has long practised a blunt form of backyard control, relying on violence, coercion, and grey-zone warfare. In many respects, Moscow has been more transparent about its intentions than Washington. Maduro’s removal is unlikely to alter this calculus. Ukraine sits at the core of what Russia calls its “near abroad,” and bringing it under control is framed in Moscow as both a historical entitlement and a strategic necessity.

Yet the war has also exposed the doctrine’s limits. Attempts at domination can trigger protracted, self-defeating conflicts that erode the very power they are meant to secure. If Russia has struggled to defeat Ukraine after four years of war, its capacity to threaten larger NATO powers looks far less formidable than often assumed.

With China, the parallel is Taiwan, coveted not only for its strategic position but for its advanced semiconductor manufacturing. The United States has limited appetite for war over Taiwan, but that alone is unlikely to provoke Beijing into rash action. China is the most calculating of the great powers. It will not jeopardise decades of economic integration with the global system by launching overt aggression. Hong Kong offers the model instead: suffocated and absorbed without a shot being fired.

For Europe, the message is unmistakable. You are increasingly on your own. The United States no longer sees itself as the guarantor of European security, and it is adjusting its commitments accordingly.

Beyond territorial influence, clearer spheres of expertise are beginning to take shape. Great powers are no longer competing solely for land or allies, but for dominance across economic domains.

The United States is reinforcing its advantages in technology, energy, and space. Russia, increasingly constrained, leans heavily on oil, gas, and a permanent war economy. China is consolidating control over critical minerals and manufacturing supply chains. India is positioning itself to compete with China as the engine of the global customer-fulfilment economy. Power today is secured as much through control of economic networks as through command of land or sea.

What is striking is not the novelty of this shift, but its brazenness. This trajectory did not begin with Trump. It accelerated under Obama, continued under Biden, and is unlikely to be reversed by a future Democratic administration.

The difference now is that the pretence has been abandoned. Grenada, Panama, Haiti: history is reasserting itself. International law is not disappearing, but it is being quietly downgraded in favour of raw power. The World Trade Organization and the World Health Organization, once central pillars of the global order, are increasingly marginalised. The United Nations looks ever more impotent.

These changes are unlikely to be reversed. In a world of sharpened multipolar rivalry, power is no longer measured by how far a state can reach, but by how firmly it controls the physical, economic, and technological space closest to home.