Politics

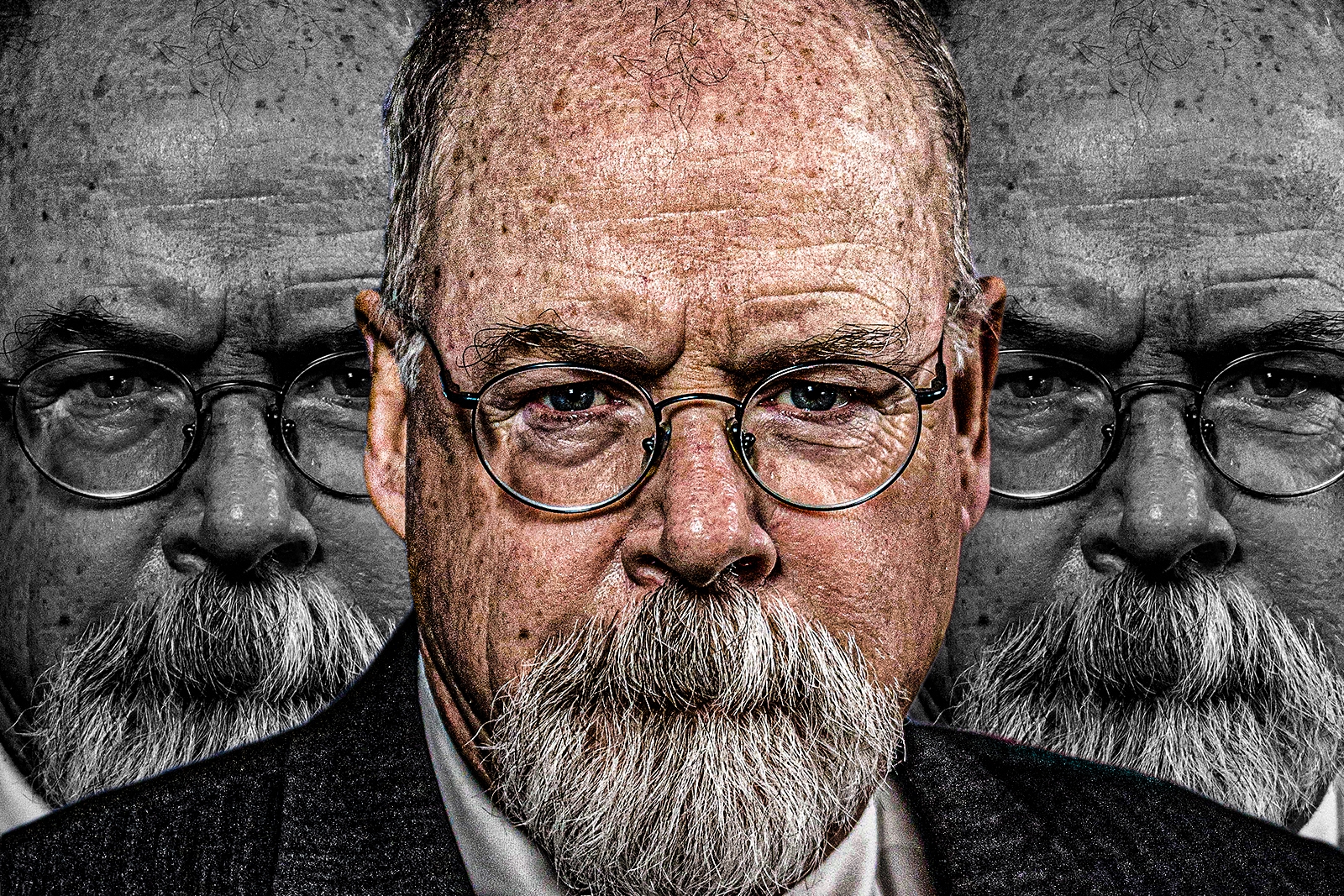

The Shame of John Durham

Special counsel John Durham first brought his indictment of Michael Sussmann in September of 2021. Ever since then, his conduct has wavered between total embarrassment and general incompetence, with it all culminating in his first humiliating loss after a jury recently found Sussmann not guilty. Given that federal prosecutors have a general success rate of 99%, and special counsels have near-unlimited resources, the humiliation is exponential. But by all indications, it hasn’t deterred Durham, or his supporters.

In the early days of Sussmann’s indictment, conservative media treated Durham as a retributive force that was finally going to right the wrongs of the Russia investigation. However, as the trial went on, more and more people on the Right slowly came to the realization that Durham did not, in fact, have the goods. His single-charge indictment (of which there was only one witness to the supposed crime) was — it turns out — as weak as “liberal media” described.

The tone then shifted, and many of those who described Durham’s case as a clear-cut win did an about-face, stating that a “not guilty” verdict was always going to be the outcome. The argument then became that it wasn’t about securing a guilty verdict but giving Durham an opportunity to tell his story: That Trump was framed by the Justice Department, the FBI, and the Democratic Party, and any allegation that his 2016 campaign coordinated with Russia was a grand conspiracy cooked up by his opponents. Durham was unable to tell that story because it is patently untrue, but it remains the almost sole justification for him continuing the investigation.

In September of 2021, the Federalist’s “senior legal correspondent,” Margot Cleveland, identified arguments about the weakness of Durham’s case as one of the “Five False Narratives” related to the indictment. She said: “While the ‘That’s it[?]’ crew hedged their coverage with passing caveats acknowledging Durham may yet come forward with more charges, they seemed genuinely convinced that would not happen. Given the details included in the indictment, that’s truly a bizarre stance to strike.”

Additional charges against Sussmann did not, in fact, come forward. Reading Cleveland’s old piece and her criticism of “liberal” commentators shows that the original weaknesses identified in Durham’s indictment were completely justified. Members of the jury in the Sussmann trial generally described it as a waste of their time.

As the trial went forward, Cleveland was able to read the tea leaves and decided to pivot. She shifted her tone and said that the Sussmann trial was more about the journey, rather than where we ended up: “[W]hether [Sussmann] ever faces a conviction says nothing of the success of the Durham investigation. To date, the special counsel has succeeded in exposing Hillary Clinton’s role in the hoax — and that the Alfa Bank hoax was real and spectacularly scandalous.”

It should be obvious, but this isn’t the role a prosecutor is supposed to take. The point of an indictment isn’t to “tell a story” (although that may be a secondary goal), but rather to actually secure a guilty verdict. The Department of Justice clearly says this in their own manual:

“The attorney for the government should commence or recommend federal prosecution if he/she believes that the person’s conduct constitutes a federal offense, and that the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction […] Evidence sufficient to sustain a conviction is required under Rule 29(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, to avoid a judgment of acquittal. Moreover, both as a matter of fundamental fairness and in the interest of the efficient administration of justice, no prosecution should be initiated against any person unless the attorney for the government believes that the admissible evidence is sufficient to obtain and sustain a guilty verdict by an unbiased trier of fact (my emphasis).”

Also noted:

“[T]he attorney for the government’s belief that a person’s conduct constitutes a federal offense and that the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction is not sufficient standing by itself to commence or recommend prosecution. The prosecution must also serve a substantial federal interest, and the prosecutor must assess whether, in his/her judgment, the person is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction; and whether there exists an adequate non-criminal alternative to prosecution (my emphasis).”

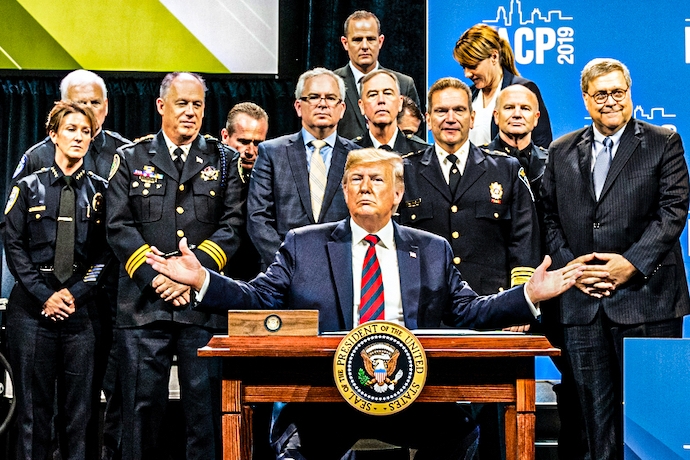

The person who appointed Durham has essentially admitted (in public), that Durham’s ultimate goal violates every single one of these principles. During an interview on Fox News last week, former Attorney General William Barr openly stated that the purpose of the Durham investigation isn’t to secure convictions. Barr essentially said that it’s to tell a different narrative than the one described by the Mueller investigation and the Senate, which was that there was significant coordination between the Trump campaign and Russian intelligence forces during the 2016 election, even if it wasn’t criminal.

He cavalierly stated in an interview that, “[Durham] accomplished something far more important” than securing a guilty verdict, which was that they got the alternative “story out.” It’s truly bizarre that Barr made this statement publicly, and absent pre-senile dementia, it’s hard to find a credible explanation for it. But he still said it, and — in doing so — made Durham’s job all the more difficult. Namely, Durham still has one more case to try: The five-count indictment of Igor Danchenko, who (like Sussmann) supposedly lied to the FBI in interviews.

Danchenko will not have the legal team Sussmann had at his disposal, but any competent attorney will cite Barr’s statements and allege that Durham’s entire investigation is a political vendetta waged on Barr’s behalf. This says nothing of Durham’s own convictions about his case (there is a credible argument that he truly believes in its merits), but a consumption of too much Fox News is not a sustainable defense against potentially prosecutorial misconduct.

In fact, Durham’s conduct during the trial itself was troublesome. Testimony on the stand revealed that many of the prosecution’s witnesses had been pressured by the special counsel into giving favorable statements to the government. Durham’s team also violated multiple rules of evidence set forth by Christopher Cooper, the presiding judge. Given Barr’s statements and Durham’s conduct, it is clear that — at the very least — some oversight is warranted.

Thus, there are two means of oversight that can be used in this instance, and both have credible counterarguments. However, neither of these arguments really outweigh what is fully supported by the evidence: Shutting down Durham’s political score-settling would be a net benefit to the country.

Attorney General Merrick Garland should shut down Durham’s investigation, or tell him to issue a report right now.

As noted above, the only remaining case on Durham’s docket is the indictment of Danchenko. While some in the press have treated this as more credible than the Sussmann case, experts have noted that it suffers from many of the same deficits. Garland may be tempted to let the Danchenko case play out, but by all indications, a predictable pattern will follow: Conservative media will insist that the case is a lock, and when the weakness of the case is made obvious, the argument will shift to Durham’s “story” being more important than securing a conviction.

Garland can head this off by firing Durham, as is his right (as was President Donald Trump’s right during the Mueller investigation, which — to Trump’s credit — was allowed to proceed). The counterargument is that doing so would create a media circus and give Republicans the means to conduct multiple investigations once they obtain control of Congress in November. But this doesn’t hold weight for two reasons:

After his investigation is over, Durham is going to issue a report. He may even be writing that report right now. Assuming that the Danchenko case does not result in a guilty conviction, Durham will likely complete his report in the Fall, right in time for Republicans to assume control of Congress and hold hearings about Durham’s “findings” early next year. In other words, Congressional investigations are going to happen regardless. By firing Durham now, Garland ends a political witch hunt and saves taxpayers some money, and it will ultimately not have any real effect on what will happen after he releases his report.

Conservative media treated the Sussmann indictment as their opportunity to debunk the “Russia Collusion” narrative. When that didn’t materialize, they simply pivoted and promised that “more” would be coming at some point in the distant future. Once the Danchenko case proves to be less than earth-shattering (even if a guilty verdict is secured), conservative media will do the same pivot. Much like Republican oversight, a media circus is coming no matter what the outcome is of Durham’s remaining case.

The House Judiciary Committee should call on Durham to testify in front of Congress.

One of the most important roles of Congress is oversight of the Executive branch. Durham is an employee of the Department of Justice, so even if Garland is reticent to act, Congress has credible reasons for taking a look at how Durham is spending taxpayer dollars.

Again, there are counterarguments to marching Durham in front of Congress.

Obviously, it will look like Democrats are interfering in an investigation of what is (ultimately) the Obama administration’s conduct. But that is a fantasy that only penetrates the right-wing bubble: The inspector general of the FBI has already found that the investigation into Trump’s campaign was properly predicated, with no political bias. That has mattered little to conservative media and (alarmingly) Durham himself, who stated publicly that he disagreed with the report. In reality, the reasons the Trump campaign was investigated by the FBI is because members of his team presented “grave counterintelligence threats” to American security.

The ranking member of the Judiciary Committee is Jim Jordan, who will purposefully make any hearing a shitshow. Other members include Matt Gaetz, Andy Biggs, and Chip Roy. Questions from these members of Congress will allow Durham to expand on his conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton campaign’s “collusion” with the FBI. But — as noted above — this is coming anyway. Once Republicans take control of Congress, their “oversight” will consist of them calling Durham to testify about all the damaging information in his report (save for Matt Gaetz, who may well be indicted by then). The argument against calling for Congressional oversight of Durham now is merely an argument for delaying it.

One of the more alarming things about Durham’s investigation became evident during the trial itself. While it was somewhat understood that a tech executive who worked with Sussmann — Rodney Joffe — was being threatened with prosecution by Durham’s team, an FBI agent on the stand actually said that he was currently a potential suspect in a criminal case, or that was the impression he had gotten from the special counsel.

Marcy Wheeler details how Durham’s team basically “coached” witnesses into changing their testimony: “Thus far, Sussmann’s cross-examination has elicited evidence that at least three witnesses changed their testimony after interviews with [Durham deputy Andrew] DeFilippis, adopting a ‘memory’ that conflicts with the documentary record with regards to whether the FBI believed the white paper to be associated with the DNC.”

In light of this conduct, it is pretty clear that Durham’s team is going to pull the same stunts with the Danchenko prosecution, and — unlike Sussmann — he will not have a team of high-profile defense attorneys to assist him. And, if the Justice Department truly believes it can actually secure a guilty verdict in Danchenko’s case, it can be handed off to a federal prosecutor and lose the stench of Durham’s investigation.

Although recent reporting has suggested that Merrick Garland is reticent to stop Durham’s probe, the downsides of letting it continue far outweigh the political repercussions that would ensue after it is shut down. Garland should allow the facts to speak for themselves, fire Durham, and let Republicans continue screaming into the ether.