Culture

The Surprising Deep Friendship of America and Japan

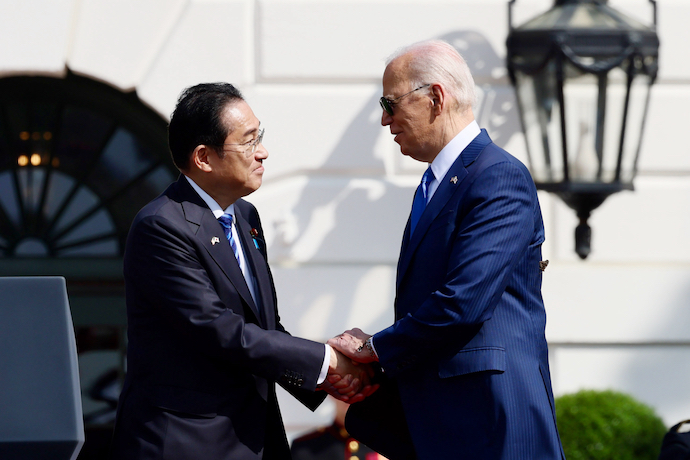

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit to the United States is a continuing trend in the long history of U.S.-Japan relations. The United States has never lacked effort in maintaining its political and economic ties to Japan, and the state dinner for the Japanese prime minister by President Joe Biden is a testament to the importance Washington places on its connection to Tokyo. The Japanese delegation’s joyous arrival and delivery of Sakura (cherry blossom) trees to replenish Washington’s Sakura trees planted in 1912 are symbolic of the ongoing synchronized relationship between the two countries.

President Millard Fillmore commissioned the opening of relations with Japan by Commodore Matthew Perry during the 1850’s. This foreign policy initiative was intended to give life to commercial interests through trade agreements and open ports beneficial to the United States. The United States Department of State had previously been able to conduct diplomatic and economic relations with China, but not Japan. Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa Shogunate, which was a military dictatorship that ruled with a feudalistic and isolationist ideology. The U.S. and Japan were successful in creating conducive relations, and this opening of Japan contributed to modernity, innovation, and globalization within the Japanese way of life and government. Commodore Perry’s voyages had a lasting impact on Japan and directly led to the abolishment of feudalism and the shogunate by virtue of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

The Japanese affection for the United States never wavered in the decades after the Perry expedition. To be specific, Japan turned to President Theodore Roosevelt to help broker a peace agreement to end the hostility between Japan and the Russian Empire after the Russo-Japanese War from 1904 to 1905. Roosevelt was trusted by the Japanese to be the chief negotiator and unifier during the peace talks. After Roosevelt successfully negotiated the Treaty of Portsmouth between Russia and Japan, he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906. The Japanese cherished their American friends so much that a few years later in 1912 a delivery of three-thousand Japanese Sakura trees were planted throughout Washington, DC, and are there to the current day.

After the end of the Second World War, the Truman administration authored and implemented a mutual defense agreement with Japan that gave the United States broad powers over the defeated Axis powers. It was revised years later to be more equitable for Tokyo and agreed to by the Eisenhower administration. Japan was always an American point of interest, especially in the context of a newly unified Communist China in 1949. It was in the interests of American foreign policy to maintain its presence in this part of the world. During the 1980s, Japanese ingenuity and economic success turned the global economy upside down. Japan harnessed capitalism and free markets to become a global business and trade juggernaut. Tokyo was in an enviable position to project its business presence in global finance and commerce. Political scientists at the time predicted that Japan would become the undisputed hegemonic power, and the United States would lose its superiority.

President Ronald Reagan made great efforts to coalesce business ties with Japan, and his relationship with Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone was unshakable. The Reagans and Nakasones frequently met to discuss global political and economic matters, as well as socialize on a personal level. Reagan welcomed Nakasone to Camp David to discuss Japanese innovations in technology and trade in addition to global nuclear security, and the Japanese leader was one of the few foreign leaders who was given unrestricted access to the vacationing Reagans.

During a Japanese visit in 1986, Ronald Reagan said: “Our meeting has reaffirmed my conviction that the close relationship between us is of immense importance for our two peoples and for the rest of the world. The friendship between our two nations is mirrored in the personal respect and affection that the Prime Minister and I have for each other, an affection that is held also by the Japanese and American peoples. Yesterday at Camp David and this morning here at the White House, we had, as always, much to talk about. In discussing relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, including arms control, the Prime Minister expressed his support for efforts towards the convening of a summit meeting with the Soviet Union. We agreed on the need for the democratic nations to remain united. We also reviewed our defense relationship and reaffirmed that the U.S.-Japan treaty of mutual cooperation and security is the foundation of peace and stability in the Far East and the defense of Japan.”

The U.S.-Japan relationship was cemented during the 1980s after the fascist interregnum that led to the U.S. oil embargo against Japan and Japan to conduct the attack on Pearl Harbor and join Germany and Italy in its war against the allies.

In the decades since, China has become a regional hegemonic power with ambitions to fully control the Indo-Pacific region by strengthening its grasp on Taiwan, allying with nuclear North Korea, and thwarting the U.S. by joining Russia in opposing any Western geopolitical moves that would embolden Washington. President Biden’s meeting with Prime Minister Kishida seeks to be a counterweight to China’s projected power within the Indo-Pacific region.

The only point of contention between Japan and the U.S. currently is that President Biden opposes Japan’s Nippon Steel attempting to acquire U.S. Steel. As Professor Joseph Nye asserted in the New York Times, he believes this is an unwise policy, especially because Japan has been a stalwart ally of the U.S. Joe Biden firmly maintains that he will not allow American workers to suffer because of Japanese business interests and will side with the American unions. 2024 is an election year and the American president is careful not to give his main opponent fuel for criticism. Prime Minister Kishida’s control of his party is set to expire, and he will need to run a reelection campaign as well. The summitry and pageantry of his trip to the United States is meant to embolden his political standing and foreign policy bona fides. Both leaders have much to gain from this relationship if played to their respective advantage.

Central to the American counterweight strategy against China are the regional alliances that serve as obstacles to Beijing’s ambitions in the Indo-Pacific region. AUKUS and the Quad have been fundamental building blocks in the mission to curb China’s regional ambitions. As the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia have steadfastly agreed to maintain an alliance in the region countering China, Japan has been its greatest supporter and meeting point for negotiations, surveillance, trade, and security initiatives for AUKUS.

Japan, itself, will not militarize in the foreseeable future because of constitutional constraints on its military apparatus. This has enabled NATO to use Japan as leverage against China and Russia in global security relations. Because Japan willingly supports AUKUS and NATO, it supports the security dialogue between the United States, India, and Australia, and itself as a meaningful venue in regional security relations to compensate for its lack of military presence and membership in multilateral security partnerships. Japan is willingly seeking a role with the Western powers to influence regional affairs in its favor.

The Japanese sense a moment of opportunity as the Indo-Pacific is becoming the center for global security and economic affairs. The U.S.-Japan alliance has many convergent issues that both governments realize create a necessity for future prosperous relations. North Korea, China, Taiwan, and the South China Sea are security flashpoints that cement the U.S.-Japan alliance, but the rise of China’s global economic status as a competitor to the United States and the unrivaled economic power in the Indo-Pacific region after Japanese economic stagnation will continue to mold the U.S.-Japan relationship for decades. If history is any indicator, the United States and Japan will act in unison on the world stage because their joint interests and shared history of friendship will make this a non-negotiable necessity.