The United States Rolls Out the Red Carpet for Kenya

In December 2002, former President George W. Bush welcomed Daniel arap Moi of Kenya and Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia to the White House. The timing of the invitation of the two African leaders is straightforward. A little over a year before, September 11 happened.

The agenda of the meeting with Moi and Zenawi was to bring both leaders to the table as “partners” against the “global war on terrorism.” As reported by the BBC, Bush described the two leaders as “two strong friends of America…two leaders of countries which have joined us to fight the global war on terrorism.”

After the brief address by Bush, both Moi and Zenawi spoke as they underscored their full support of the war on terror. President Moi stated that he was most concerned with the security in and around his country and the global fight against terrorism. President Moi’s security concern “around his country” was mainly referring to Somalia. On the other hand, unsurprisingly, the language used by Zenawi was stronger than that of Moi. Zenawi affirmed his belief that the war against terrorism “is a war against people who have not caught up with the 21st century; people who have values and ideals that are contrary to the values of the 21st century.” He continued, noting that the war “is not a fight between the United States and some groups; it’s a fight between those who want to catch up with the 21st century and those who want to remain where they are.”

Eventually, Meles Zenawi was “crowned” as the trusted partner in the Horn of Africa to execute the agenda of the “global war on terrorism,” and the target country to watch was Somalia.

Zenawi went above and beyond in his ill-advised interferences in Somalia both politically and militarily. In 2004, he played a key role in the establishment of a warlord-led transitional government in Mbagathi, Kenya. In mid-2006, with overwhelming popular support, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) came to power as they defeated the warlords who had failed to provide the Somali people with either governance or security. However, Zenawi invaded Somalia, crushing the ICU, and because of this, al-Shabaab was born, increasing their operations inside Somalia and their threat to the wider Horn of Africa region. In 2007, the first batch of African Union forces, mostly Ugandan soldiers, came to Somalia for a peacekeeping mission as Zenawi “withdrew” his forces from Mogadishu after several bloody battles and resistance from the people of Mogadishu.

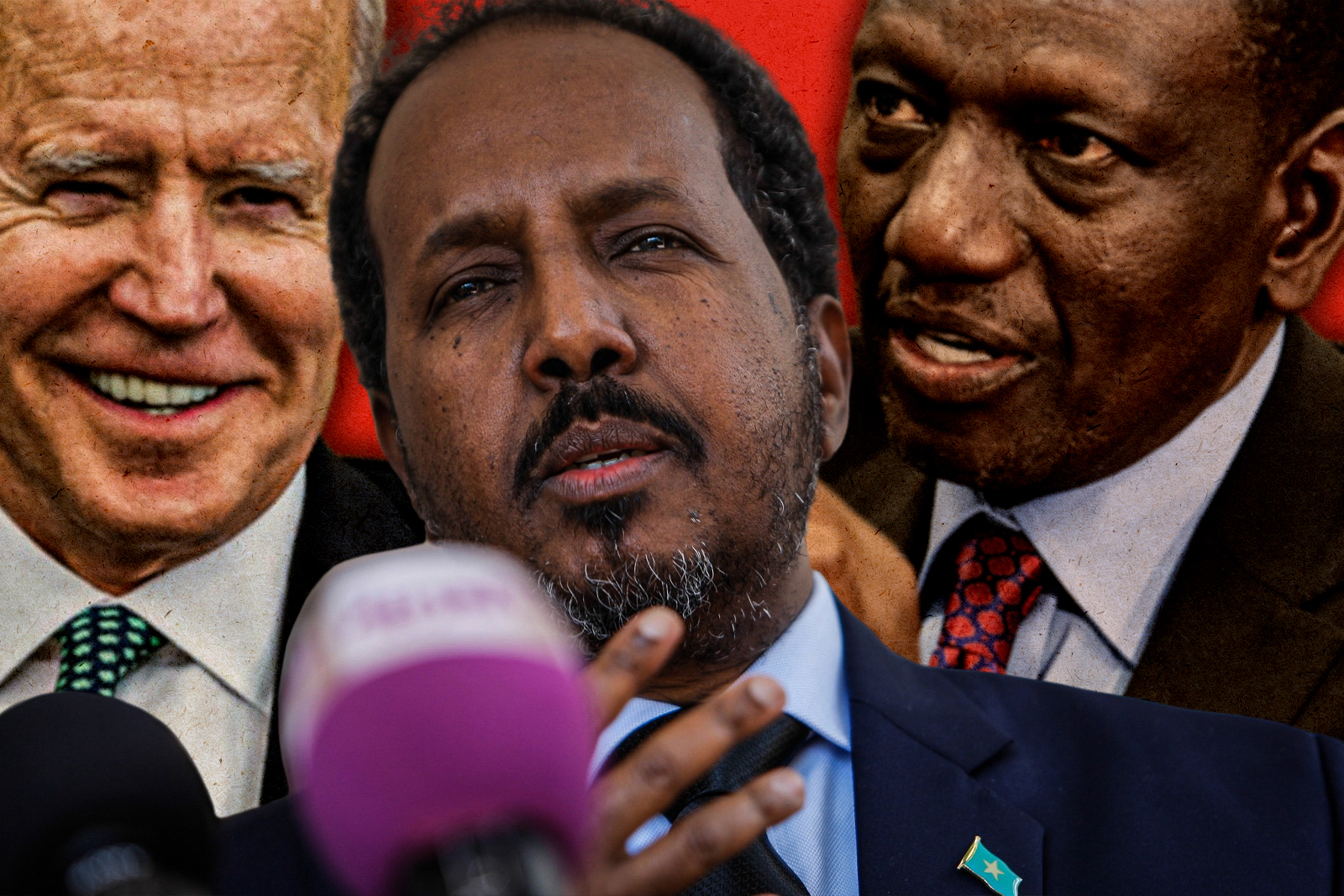

As the “global war on terrorism” that Bush started continues today, Ethiopia has failed to be a reliable partner under the current conditions, and the U.S. must look for another partner to continue the mission. As a result, the Biden administration has embraced Kenyan President William Ruto with open arms. On May 22, President Ruto came to the United States for an official state visit to the White House. President Ruto’s visit is described as the first state visit by an African head-of-state to the White House since 2008. However, the question is, what does this new partnership mean for the region?

According to the Biden administration, the partnership between Kenya and the United States is based on four pillars. The first pillar is to designate Kenya as a major non-NATO ally. Even though this designation may have a wider objective, it can be attributed as a reward for the recent decision of Kenya to send 1,000 security personnel to Haiti. The second pillar is to launch what is termed “the Nairobi-Washington vision.” Under this pillar, it is stated that the objective is to mobilize resources for countries saddled by debt, open opportunities for private-sector financing, and promote better lending practices. Cooperation on technology is the third pillar of the partnership. The aim of this pillar is “to bolster artificial intelligence, semiconductor, and cybersecurity partnerships as well as expanding STEM education and Internet access across East Africa.” The fourth pillar is “strengthening people-to-people partnerships.” The objective of this pillar is to enhance the democratic principles that connect the two peoples.

With those four pillars, however, security is the top critical element of the new partnership between Kenya and the United States. The security pillar can be considered the main objective behind Ruto’s state visit to the United States. In his address at the White House reception, President Ruto stated that he is confident that the partnership between the United States and Kenya will provide solutions that the world so desperately needs. Mr. Ruto touched upon the “heavy lifting Kenya is doing” when it comes to peace and security in the Horn of Africa and Great Lakes regions. Even though the Great Lakes is mentioned here, the critical security threat that the United States and Kenya are partnering with is the one that emanates from the Horn of Africa.

To suppress the threat from al-Shabaab, Kenya invaded southern Somalia in 2011 and then officially became a member of the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM). Al-Shabaab has targeted Kenya three times since 2013. In 2013, al-Shabaab attacked the Westgate Mall in Nairobi killing sixty-seven shoppers. In 2015, the terror group carried out a horrific attack at Garissa University, leaving 148 people dead. And in 2019, al-Shabaab targeted the DusitD2 Hotel in the Westlands area, resulting in 21 fatalities.

In order to address these challenges, the United States wants a reliable partner in the Horn of Africa, and at this moment, Kenya is the only country that can fulfill the conditions for several reasons.

First, despite some fragility that may surface after elections, Kenya can claim a more robust democracy compared to any other country in the East Africa region. Kenya’s transition to democracy started in 2002 after Daniel arap Moi, who ruled the country since the late 1970s, left office. In 2007, Kenya was on the brink of collapse as ethnic conflict erupted after Raila Odinga rejected the election results that favored his rival, Mwai Kibaki.

It is important to note that Kenya’s democracy has been maturing since 2013. The last election is a testament to this, as the well-established Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of the first Kenyan president, was defeated by William Ruto, an individual with no establishment in the elite system that the British colonial power left behind.

Unlike other countries in the East Africa region, Kenya has an open door for foreign investors and serves as a hub for the East African economy. This positive investment climate makes Kenya attractive to international firms seeking a location for regional or pan-African operations. This is an area that the United States wants to tap for its multinational corporations, competing with other economic rivals, including China, which has a significant infrastructure investment in Kenya. Ruto’s objective is to bring foreign investment to his country, attracting multinational corporations and boosting Kenya’s labor force. He claims that he is neither facing West nor East but facing forward.

Kenya’s military has established a strong presence in southern Somalia, and this will likely continue in the foreseeable future, whether under the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), formerly the African Union Mission to Somalia, or through unilateral or bilateral agreements with the Somali government. Kenya is also poised to play a leading role in any post-ATMIS combat operations against al-Shabaab in Somalia. As a designated non-NATO ally—the only country in sub-Saharan Africa to receive this status—Kenya will get all the material support it needs to confront the security threat posed by al-Shabaab in the Horn of Africa.

Through coordination with AFRICOM, the support Kenya will receive from the United States will include AI and cybersecurity as stipulated in the third pillar of the new partnership. Finally, it is important to note that the new U.S.-Kenya partnership signifies the end of the security partnership between Ethiopia and the United States in the “war against terrorism” that started in 2002. Kenya is now the official partner in addressing the security challenges in the Horn of Africa.

This all begs the question of the implications for Somalia. Somalia remains unstable not only security-wise but also politically, as Somalis cannot even agree on how to govern themselves. This is a sad reality, and that is why there is an ATMIS and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) in the country. The insecurity due to the threats of al-Shabaab, combined with the political impasse among the elites, enables countries with strategic interests to effectively plan their interventions. This is why the new partnership between the United States and Kenya was introduced.

By critically examining the security conditions in Somalia, the planned drawdown of ATMIS forces, scheduled for December, appears uncertain. Even though President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has initiated a war against al-Shabaab, completely liberating the country from the group will take time. However, there are two likely scenarios. The first is the possible extension of the ATMIS timeline for another year, a decision that will be made by the UN Security Council before the end of 2024. The second scenario is the initiation of another African Union mission led by Kenya sometime in 2025. In the process of these two scenarios, Somali officials will, of course, be consulted, but the final decision will be made by the UN Security Council.