The Viking in Corporate America

With just cause, a recent spate of journalism has deplored the absence of culpable Wall Street executives in federal jail cells across America. Major investment banks perpetrated systemic fraud against the public and wrecked consumer confidence in the credit and housing markets, contributing to the 2008 financial meltdown; yet, their most complicit leaders still do business, uncounted, uncharged, and unpunished.

Government regulators and lawyers often explain the delayed justice. Legal cases against major investment banks, they hold, require sharply drawn lines of evidence; common-law fraud claims, for example, require demonstration of criminal intent. Federal regulators, moreover, hate to approve bailouts to big banks and watch that recovery money pay legal fees rather than create new jobs. Prosecutorial zeal against mortgage-bundling banks also discredits the efforts of well-intentioned federal housing officials to boost homeownership rates.

Historically, few executive corporate malefactors have evaded justice as skillfully as the class of 2008. Enforcement and punishment have waned since the late 1980s when prosecution of banks responsible for the saving and loan crisis sent more than 800 officials to jail. Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse records that in 1995, bank regulators referred 1,837 cases to the Justice Department; in 2006, that tally declined to 75; from 2006 to 2010, an average of 72 cases a year have been referred to Justice for prosecution. The 2002 Enron meltdown resulted in a twenty-four-year jail sentence for company president Jeffrey Skilling.

So far, the 2008 Wall Street collapse has resulted in zero jail time for executives responsible. Bloomberg Businessweek reporter Roger Lowenstein recently explained that “risk-taking and stupidity aren’t criminal.”

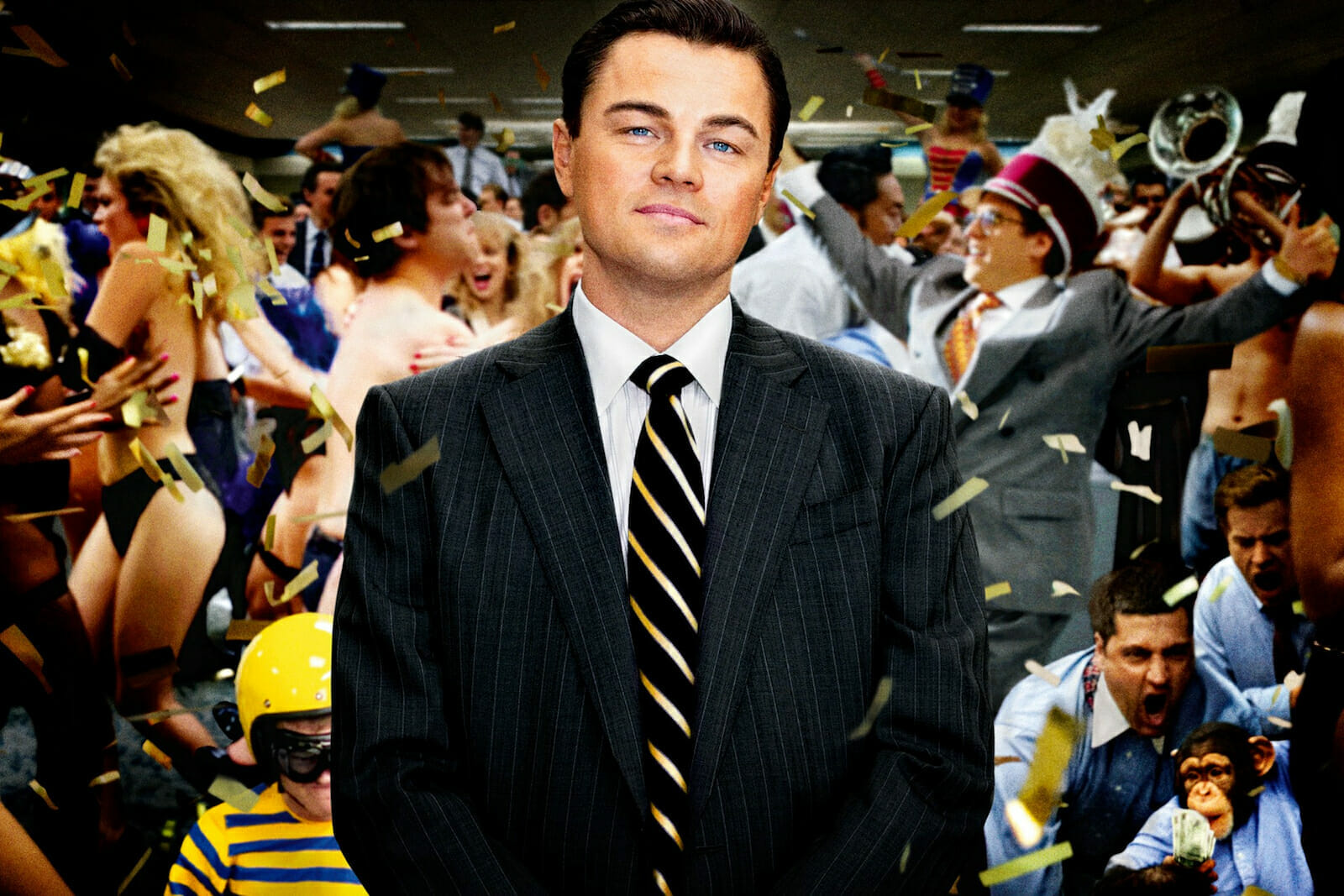

When government and corporations fail to provide answers to our inquiries and outrage, sometimes art is the only medium that speaks to the origins of criminality.

Perhaps the best script for the cultural roots of U.S. corporate malfeasance is the 1992 film Glengarry Glen Ross, an adaptation of David Mamet’s 1984 Pulitzer Prize-winning play. Hollywood cannot tell us about why the recession happened on a macroeconomic, technical level, but it does reflect values. For millennial generation youth, the TV room or movie theater is a classroom for corporate ethics as much as business school. Glengarry Glen Ross features a Chicago real estate firm selling the worst lots in Florida.

In the opening scene a braggadocio salesman from downtown, Blake, introduces a new sales contest to entice the underperformers to sell more property, “The good news is – you’re fired. The bad news is – you’ve got, all of you’ve got just one week to regain your jobs starting with tonight. Starting with tonight’s sit. Oh? Have I got your attention now? Good. ‘Cause we’re adding a little something to this month’s sales contest. As you all know first prize is a Cadillac El Dorado. Anyone wanna see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired. Get the picture? You laughing now?” Blake speaks for the prevailing corporate ethos, wherein “a man is his job”; not just their livelihood is at stake in the contest but their manhood.

To him and his peers, “only one thing counts in this world: get them to sign on the line which is dotted.” A successful businessman not only lies with glee to the consumer to ink a deal, he brandishes the trappings of wealth. Like the fictional corporate icon of the film Wall Street, Gordon Gekko, Blake flashes the gold watch, the BMW, and the exquisite suit. Status markers, even fictitious ones, set up the next sale; junior salesmen claim to be “vice president of the company, just come in from out of town,” to impress potential buyers over the phone.

An August 2006 e-mail exchange between investment bankers at the now-extinct Bear Stearns, reported recently in TIME magazine, sounds like dialogue from Glengarry Glen Ross. A supervisor sent a note to a junior banker pitching the firm’s mortgage bond deals to clients, in which he called a particular bond a “sack of s**t” and wrote “I hope your [sic] making a lot of money off this trade.” Somewhere in Wall Street, beyond the hyped jargon of subprime mortgages, foreclosures, and government-sponsored home ownership drives, lurk many a salesman just like Blake, pitching packaged loans no better than Florida swampland. 80’s American executives liked to compare themselves to Viking raiders. The Vikings of centuries past made their violent reputation as raiders of affluent British monasteries. They struck the weakest, fought hard, and fled rich.

Ironically, the modern Viking model of corporate behavior—especially for the executive suite—enumerates values antithetical to the American stereotype. The Swedish business ethic is a fine reference point for U.S. regulators looking to describe Wall Street fraud. The Swedes value moderation—what they call lagom–in all matters, including business. Legend tells of a meeting of Vikings concluded by the drinking of mead from a common bowl; everyone drank a little to leave enough for the next man. The bowl went laget om, or “around the group.” Respect for lagom entails that businessmen refrain from yelling or bragging in meetings and speak only when necessary and sincere.

Swedish businesses value consensus and egalitarianism more than American firms. Scandinavian legend tells of a Frankish prince sent as an envoy to speak with a shipload of Viking raiders targeting Paris. The prince returned to the Frankish court without a response, “I found no one to talk with,” he explained. “They said they were all chiefs.”

Another Scandinavian precept, Jantelagen, preaches self-restraint and humility at work and at home. Swedish executives make far less than U.S. ones. Swedish workers enjoy more leisure time than American ones; those who work extra hours in Sweden are often seen as inefficient rather than passionate or ambitious. IKEA, perhaps the most high-profile Swedish firm operating in the United States, and the world’s largest furniture retailer, promotes “togetherness, cost-consciousness, respect, and simplicity” to prospective employees—values contradictory to American notions of individualism, indulgence, and status-driven consumption. IKEA struggles to live up to such sweeping value statements. The Economist has reported on the firm’s record of tax evasion. But it’s the vocabulary and cultural roots of its corporate aspirations that are interesting and distinct.

Even the disparity in coffee culture between the U.S. and Sweden provides insight into the rot of American executive ethics. One Swedish custom holds that the highest-ranking executive at a firm should serve coffee to meeting attendants, rather than the lowest-ranking assistant. Corporate America has his own rules for coffee, Blake explains in Glengarry Glen Ross, “Put. That coffee. Down. Coffee’s for closers only.”