Health

Thomas Pogge on Inequality, Innovation, and the Future of Human Rights

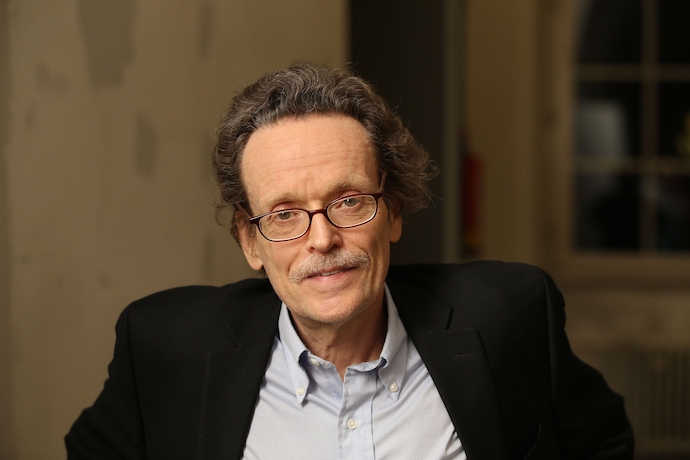

Thomas Pogge, a Harvard-trained philosopher now the Leitner Professor of Philosophy and International Affairs at Yale, has spent decades probing the ethical fault lines of global inequality. A member of the Norwegian Academy of Science, Pogge is a co-founder of Academics Stand Against Poverty and Incentives for Global Health, initiatives designed to advance access to essential medicines through mechanisms like the Health Impact Fund.

His body of work—including World Poverty and Human Rights, John Rawls: His Life and Theory of Justice, and Designing in Ethics—wrestles with some of the most urgent moral questions of our time: How can we structure a global order that is fairer, more equitable, and truly responsive to human suffering? Through Yale’s Global Justice Program, which he currently directs, Pogge fosters interdisciplinary collaborations to build more just economic, political, and social systems.

Central to his critique is the global patent regime, which he argues deepens inequality by restricting access to lifesaving innovations, particularly as institutionalized by the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement. In response, Pogge has championed “impact rewards”—proposals like the Health and Ecological Impact Funds that would incentivize pharmaceutical and environmental breakthroughs based on real-world benefit rather than market exclusivity. These alternatives, he contends, could reduce costs, improve health outcomes, and strengthen local capacities in low- and middle-income countries.

With global health again under intense scrutiny—highlighted by Germany’s Health Minister Karl Lauterbach and the G7 Pact for Pandemic Readiness—Pogge believes the world stands at a moral crossroads. Reversing decline, he argues, demands more than good intentions; it requires bold, systemic reforms rooted in human rights and the common good.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: What is the big picture when understanding global structural reform relating to innovation, justice, and poverty?

Thomas Pogge: The way development and diffusion of innovations is socially organized has a profound distributive impact. Relying on monopoly rents as incentives, the present regime (globalized by the WTO’s 1995 TRIPS Agreement) aggravates human and financial capital inequalities by reserving innovation to well-funded corporations and requiring everyone else to pay road tolls or do without.

Doing without can mean death, as it does for millions who perish because they cannot afford lifesaving pharmaceuticals, which their originators can and do sell at thousands of times the average cost of production. After all, no one else is permitted to make or sell them. This regime is profoundly unjust, and providing an alternative would avoid such harms.

For innovations with clear, measurable social benefits or whose marginal cost of uptake is very low relative to the fixed cost of development, it would be far better to use publicly funded impact rewards based on the social benefit achieved with the innovation. Affluent users would still pay for most of the fixed cost of development, but now through the tax system, not via monopoly markups. As a result, innovative products would be far more affordable during their patent period, priced near the average cost of production.

Jacobsen: What are the key arguments in “Freedom, Poverty, and Impact Rewards” regarding global inequality and ethical responsibilities?

Pogge: Recognizing that overturning the TRIPS Agreement is unrealistic, the essay suggests offering originators the option to exchange their monopoly privileges for impact rewards. This could be done by creating sector-specific impact funds that make annual disbursements of pre-announced size, each divided among registered innovations according to the benefit achieved.

Pharmaceutical innovations would be rewarded according to their health impact, for example, green-technology innovations according to pollution averted, educational innovations according to their impact on skills and employment, and agricultural innovations according to their impact on harvest yield and reduced consumption of water, pesticides, or fertilizer. Each fund would have its own uniform metric of achievement and would reward only those innovations whose monopoly privileges had been waived for a fixed number of years.

In addition to discussing technical details, the paper also complements the moral arguments with ones that highlight the enormous efficiency gains such funds would entail by reducing expenses for multiple staggered patenting in many jurisdictions with associated gaming efforts (such as evergreening), costs of preventing monopoly infringements, costs of mutually offsetting competitive promotion efforts, economic deadweight losses, and costs due to corrupt marketing practices and counterfeiting — all of which are driven up by the exorbitant profit margins engendered by the patent regime. These efficiency gains ensure that even though introducing impact funds would constitute a huge advance for poor people, it would not produce corresponding losses for the rich. This fact makes impact funds an especially attractive (politically more realistic) reform target.

Jacobsen: How should we address the ecological crisis?

Pogge: We must reduce harmful pollution fast. Realistically and morally, this cannot be achieved by drastically reducing the human population or excluding people from modern life’s conveniences (cars, washing machines, and all the rest). We need green technologies that serve the needs and interests of (ideally) all human beings without degrading our environment. Such technologies must be developed and improved, and they must also be widely and effectively deployed and used.

There are three ways of accelerating such a transition: through constraints, penalties, or rewards. Constraints (legal prohibitions) and penalties (“carbon price”) forbid or discourage certain polluting activities and thereby foster the development and use of greener substitutes. Rewards incentivize the development and use of greener products through premiums based on the environmental harms they avert. All three approaches have a role to play; my work has focused on the neglected third approach.

The crisis persists because we make far too little use of all three approaches. And what’s much worse, we are paying huge rewards for using fossil fuels. Such subsidies fall under two headings. States provide explicit subsidies when they absorb some of the costs of fossil fuel extraction and delivery or lower the sales price of fossil fuels through supplementary subventions. States provide indirect or implicit subsidies when they shield producers and consumers of fossil fuels from responsibility for the damage they cause, such as excess medical bills and the cost of environmental clean-ups and additional (not so) “natural” disasters: floods, fires, droughts, mudslides, heat waves, rising sea levels, failed crops, spreading tropical disease vectors, and so on. Under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund, researchers have produced several careful studies of these subsidies, estimating them to amount to a staggering $7 trillion per annum globally or about 7% of the gross world product.

Fossil fuel subsidies are often excused with social reasons: Transportation is essential to economic activity, and cheap transportation enhances the availability and affordability of goods and services to poor people and allows them to take advantage of distant opportunities for medical care, education, employment, shopping, and recreation. Poor people also need light in the dark hours and heating in winter. Moving as they are, these are bad reasons because the same purpose could be much better served by giving poor people in cash the equivalent of what they now receive in subsidies tied to fossil fuel consumption. The poor would be free to choose how to spend their subvention; and states would save vast amounts by not subsidizing the much greater fossil-fuel consumption of the more affluent (including fuel for yachts and private jets). Moreover, with the prices of fossil fuels reflecting their true cost, all fossil fuel consumers would shift their consumption away from fossil fuels, thereby reducing harm to our shared environment.

The abolition of explicit and indirect fossil fuel subsidies is the best thing we can do to resolve our ecological crisis. It’s not happening because the owners of fossil fuel reserves, with hundreds of trillions at stake, use their political influence to thwart such efforts. Some two centuries ago, slaveholders did the same…until they were finally bought off.

Jacobsen: How does the Ecological Impact Fund address environmental and economic concerns?

Pogge: The Ecological Impact Fund (EIF) would incentivize and reward the development of green technologies for their deployment in a defined set of lower-income countries (the EIF-Zone). The EIF would make pre-announced annual disbursements, to be divided among registered new green technologies according to pollution-caused harm averted with them in the EIF-Zone in the preceding year — with harm assessed as a weighted sum of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2eq) and lost quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

In exchange for partaking in five annual EIF disbursements, originators permanently forgo patent-based monopoly privileges in the EIF-Zone (while patent privileges outside the EIF-Zone and of unregistered innovations would not be affected). The EIF would give green innovator firms new opportunities to profit from delivering green technologies in EIF-Zone countries while letting them choose, for each innovation, whether to register it or to stick with patent privileges.

With registration optional, the EIF reward rate would be endogenous and predicably equilibrate to a stable level that is fair between participating originators and EIF funders: when originators find it unattractive, registrations dry up and the reward rate rises; when the reward rate is seen as generous, registrations multiply and the reward rate declines. Fairness among participating originators is likewise assured, as all are remunerated at the same reward-to-benefit rate.

The EIF would significantly increase uptake and impact of green technologies in EIF-Zone countries: avoiding monopoly markups would lower their price, and the incentive of impact rewards would motivate registrants to promote their wide deployment and effective use. Through enhanced profit prospects, the EIF would stimulate the development of additional green technologies that — tailored to EIF-Zone populations’ needs, cultures, circumstances, and preferences — would be especially impactful there. By thus stimulating diffusion and innovation in and for the EIF-Zone, the EIF would also build and expand local capacities to develop, manufacture, distribute, deploy, operate, and maintain innovative green technologies.

The EIF requires no international unanimity. Its main funders (possibly via the Green Climate Fund or the Global Environment Facility) could include willing European states plus China, which has greatly contributed to the global ecological crisis and has accumulated substantial wealth through highly polluting activities over many decades. Additional funds might come from international offset markets and eventually from a capital endowment built over time from treaty-based state contributions, bequests, and donations by firms, foundations, and philanthropists.

Jacobsen: How does Germany’s Federal Minister of Health, Karl Lauterbach, highlight challenges in global health systems?

Pogge: Lauterbach has repeatedly highlighted diverse global health challenges, such as healthcare workforce shortages, chronic disease management (rise in non-communicable diseases), digitalization and innovation, pandemic preparedness, climate change, and excessive health disparities. Much of this has indeed been mainly highlighting, exhortation, and advocacy. But then he was, during Germany’s 2022 G7 Presidency, the driving force behind the G7 Pact for Pandemic Readiness, which aims to enhance global health by better coordinating international initiatives, by enhancing global surveillance, and by strengthening health emergency workforces. Lauterbach’s exceptional competency, energy, and hard work make him a very impressive minister.

Jacobsen: Can you touch on pharmaceutical innovation and access?

Pogge: Exclusive reliance on patent rewards in the pharmaceutical sector is morally problematic because it imposes great burdens on poor people who cannot afford to buy patented treatments at monopoly prices and whose specific health problems are therefore neglected by pharmacological research. This effective exclusion of the poor is also collectively irrational by turning low-income populations into breeding grounds for infectious diseases, which often develop new, drug-resistant strains — of tuberculosis or malaria, for instance — and by rendering us unprepared for dealing with infectious disease outbreaks such as Ebola, swine flu, and COVID-19. Pharmaceutical companies profit by letting diseases continue to proliferate, which shows how truly dumb our patent-focused innovation regime is, especially in the pharmaceutical sector.

I argue for establishing a Health Impact Fund (HIF), which would invite innovators to exchange their monopoly rents from any new pharmaceutical for impact rewards as an alternative way to recoup their R&D expenses and earn competitive profits. Innovators would find HIF registration especially attractive for new pharmaceuticals, with which they expect to generate large cost-effective health gains but only modest monopoly rents. These would tend to be effective remedies against widespread, grave, infectious, and concentrated diseases among poor people. Many of these HIF-registered pharmaceuticals would be ones that otherwise would not have been developed at all. By promoting innovations and their diffusion together, the HIF would greatly increase the benefits and, thereby, also the cost-effectiveness of the pharmaceutical sector in favor of the world’s poor.

By fully rewarding third-party health benefits (e.g., diseases you don’t catch because others around you have been treated or vaccinated), the HIF motivates pharmaceutical firms to fight diseases at the population level. The largest rewardable impact a new medicine can have is the eradication of its target disease. To fight a disease to extinction, firms would build, in collaboration with national health systems, international agencies, and NGOs, a strong public-health strategy around their HIF-registered product, deploying it strategically to contain, suppress, and ideally eradicate the target disease. Monopoly rewards, by contrast, penalize such efforts, making disease eradication a financial nightmare for CEOs and shareholders.

Jacobsen: Why advocate for making new medicines accessible?

Pogge: Most pharmaceuticals can be mass-produced at very low marginal cost. Indian generics firms are extremely good at this. But they are prevented from manufacturing the newer products by India’s patent laws which India, in turn, is required to impose as a condition of membership in the WTO. Implementing the TRIPS Agreement in the world is actively preventing the supply of life-saving medicines to those who cannot afford to buy them at monopoly prices. Millions of people suffer and die due to patent enforcement. And all of us face added dangers and risks on account of eradicable diseases that proliferate and often mutate among the poor.

The standard response is that, without patents, there would be no new medicines for the rich or the poor. The HIF proposal defeats this response. Its real possibility shows that upholding the pharmaceutical sector’s patent regime constitutes a monumental human rights violation.

Jacobsen: What does the decline of the Western-centric world order and rise of a more rounded global order mean for the 21st century?

Pogge: I am not convinced the Western-centric world order — more descriptively, the United States — is truly declining in terms of power. It is fighting hard to maintain its supremacy, relying ever more on violence and military strength. It is an open question whether it will be able to beat down China the way it had previously beaten down Japan and the USSR. Much will depend on rapidly evolving technologies: drones, AI kill programs, autonomous fighting machines, biological and cyber warfare, clandestine regime-change and sabotage operations, etc. And, of course, there’s a fair chance that human civilization will be destroyed in this contest.

The Western-centric world order is palpably in moral decline: the gap between professed values and actual policies has never been greater, nor has public tolerance for mass killings (of the Gaza or the TRIPS sort) in the name of national interest and security. This moral decline is likely to continue but won’t lead to a world order that could be called “more rounded.”

The longer-term survival of human civilization depends on reversing this trend, on moralizing international relations in the way Gorbachev thought he had agreed upon with the U.S. Such a morally based world order is not too difficult to describe. But the path from here to there looks impossibly difficult. Who in the U.S. will agree to move toward a world order in which military power becomes irrelevant, in which international disagreements are resolved through impartial judicial or legislative procedures, and in which the needs and voices of foreigners have as much weight as those of compatriots?

To make moral progress, despite miserable odds, against the spreading tide of national selfishness, distrust, hostility, and confrontation, we must create highly visible exemplars of morality: multilateral initiatives that clearly protect human rights, promote justice and the common good of humanity, rather than merely the mutual benefit of their initiators. I see the Ecological and Health Impact Funds as plausible proposals.

Another would be a globally universal school lunch program that would secure each school-aged child one full, healthy meal, locally sourced, on every school day. The realization of this very affordable program would show that our internationally shared commitment “to leave no one behind” was more than empty words. Are the world’s more affluent countries, including China, prepared to spend about half a percent of their military outlays to fund such a program by providing the subsidies necessary to enable and incentivize poorer countries to participate? Let’s get it on the G20’s 2025 agenda and find out!

Jacobsen: Thank you for the opportunity and your time.