Turkey’s Foreign Policy is Polarizing on Purpose

Too many crises to count command the global conversation – COVID, Brexit aftershocks, America’s raucous election – yet Turkey has still birthed a barrage of stories. Its historical tensions with Greece have flared up. In Central Asia, Turkey’s alliances have come under scrutiny as Azerbaijan and Armenia resume hostilities. In the Libyan civil war, Turkey’s actions have been controversial too. For a country critical of foreign media, Turkey allows for no shortage of international headlines.

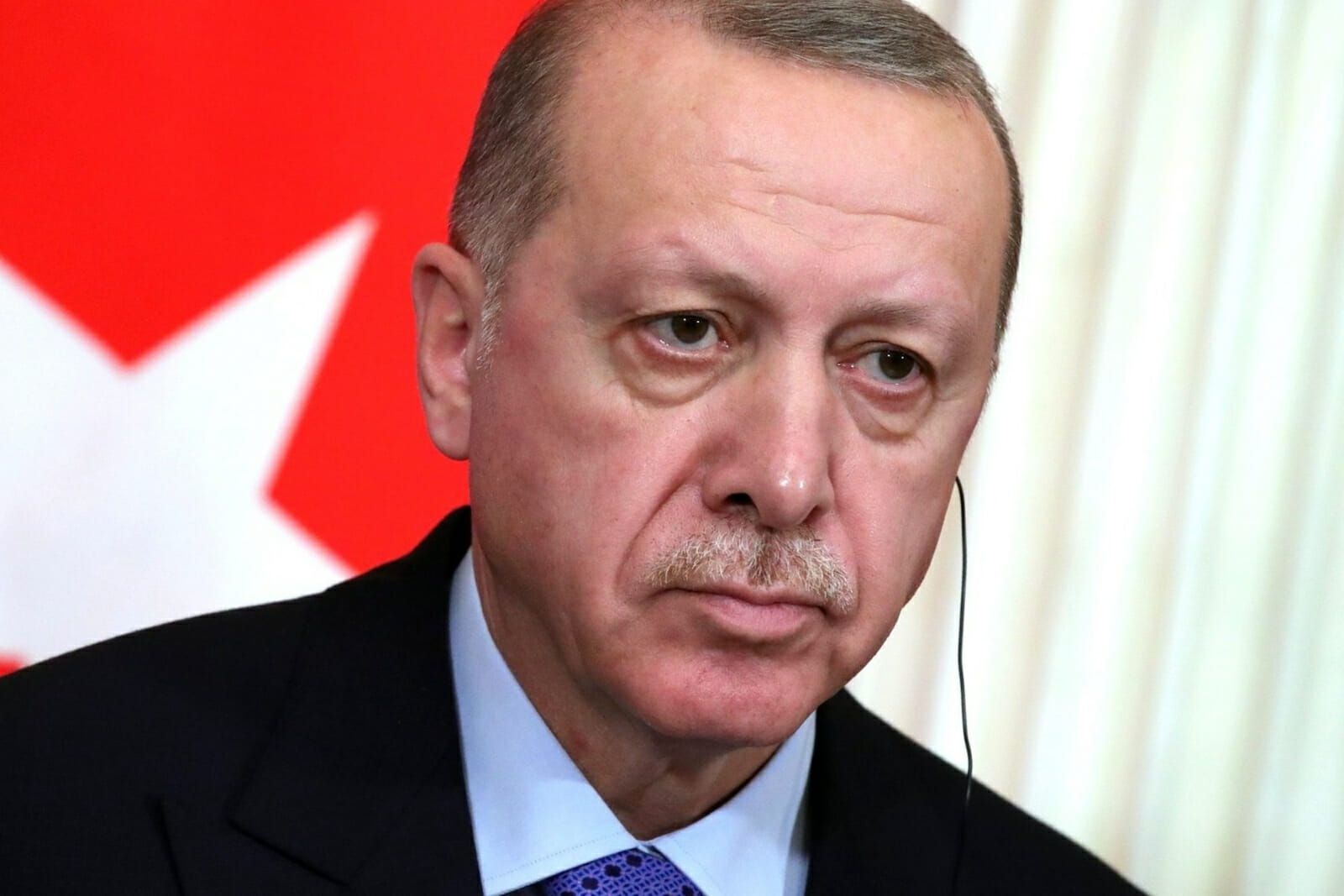

Ankara has long been at a crossroads in the international community. NATO membership, dating back to 1952, has positioned it as an ally of both Europe and the United States but that does not mean it hasn’t provoked headaches in both Brussels and Washington. As I have argued before, such complications mean NATO should ponder debates about member expulsion to reflect on what kind of bloc it is – and will be – and in the event, this mechanism ever became truly necessary. However, any move toward this historic gesture would sacrifice crucial geopolitical ties, shaking an alliance already threatened so often. Such dismissals would also damage a commitment to communication with the Turkish people, as is reasoned at the Atlantic Council, and strengthen President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s paranoid style of politics against intolerant outsiders. Thus, the ejection of Turkish membership is likely not the optimal path.

But the bloc is deeply unsure of how to respond to Erdogan’s foreign policy. It clearly struggles over its identity: is it primarily a united geopolitical front or a union of actors with similar values? French President Emmanuel Macron faces similar contradictions – his own foreign policy can blur geopolitical lines, despite his nation’s key role in the bloc. But Erdogan puts his own country’s cumbersome foreign connections centerstage, by design.

Erdogan’s foreign policy has been described by some as neo-Ottoman. While evoking the names of empires past is sometimes unhelpful, the leader’s populist rhetoric and style does imply a restoration of some element of former Turkish glory. A longtime member of the AKP, he saw his party make concessions toward European Union accession in the early 2000s, only to be left outside the bloc still. He is deeply skeptical of multilateral coalitions of which his nation is part, clearly not comfortable with reducing Turkey’s symbolic status to that of yet another member-state.

The strongest, most recent strain on the alliance comes from Ankara’s maneuvers in the Mediterranean. While maritime disputes are not uncommon here, recent explorations for hydrocarbons in waters disputed between Turkey and Greece have been deemed especially provocative. In response, tensions have risen. Greece has accelerated plans for a wall on its border with Turkey, ostensibly for immigration purposes but likely catalyzed by recent events. A recent NATO-brokered cessation of war games between the two nations is a breakthrough, but unlikely to end aggression. The alliance will, going forward, need to find long-term settlements that both nations can agree upon.

Erdogan has also deepened support for Libya’s internationally-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA). A powerful backer, Erdogan has even inked oil-drilling deals with the GNA. This has provoked both Rome and Paris. Italy, concerned with the profits of oil companies like Eni and the flow of migrants, opposes Ankara. Macron’s position in Libya is complicated but clearly opposed to Turkey’s expansion of influence.

European allies are deeply divided about how to respond. Erdogan’s militant tone toward the EU can make Turkey’s own accession bid seem like a debate from ancient history. But still many EU nations – Germany, Italy, Malta – seek to maintain their relationship with Ankara, while others – France, Greece, Cyprus – favor a harder line. Tensions with the latter two are usual. But Erdogan and Macron particularly dislike each other, with Erdogan even leading a growing boycott of French products and questioning Macron’s mental health in light of statements regarding terrorism in France. Even if some countries threaten sanctions with sincere anger, the EU is deeply divided over how best to proceed. Regardless, Erdogan is not making himself many friends in the bloc – and doesn’t appear to be trying.

Then there’s Washington. Senators from both parties have recently revived threats of their own sanctions regarding Turkey’s usage of the Russian S-400 missile system, the purchase of which some time ago was highly controversial. President Donald Trump seems more personally sympathetic to Erdogan, though relations have become more complicated between their two countries. Trump, openly hostile to NATO, doesn’t seem too concerned with its internecine fights over Turkish foreign policy. After all, he’s not a stranger to provoking controversy within NATO himself.

But even ties with Moscow are complex. Turkey’s choices in Libya, Syria, and recently in the now-rekindled Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict all complicate Russian President Vladimir Putin’s goals. Fears of a direct Turkish alignment with Moscow, and complete divorce from the West, seem overblown in context, even if Putin may hope to splinter NATO via Turkey. As Anna Borshchevskaya argues at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, even cozying up to Putin creates at best an uneasy friendship where Moscow has an upper hand. Though the S-400 system has long been a cause for concern, it is more likely reflective of Turkey’s strange geopolitical position than a direct realignment. Even Iran, with whom some cooperation exists, has its own reasons to be wary of Turkey.

All of these moves demonstrate Turkey’s strange international profile. They have also proven Ankara to be a bit of a loose cannon, for any ally, because its own interests are largely unaligned with any other power. There’s room for conflict with virtually anybody – and Erdogan enjoys brinkmanship.

Walking the line between NATO and Russia thus seems strategic. Despite contributions made to NATO, like the troops it provides, Erdogan sees Ankara as a great power – unwilling to relegate itself to strict cooperation with a specific bloc or key ally. To him, Turkey is a transcendent power, and the Turkish people deserve to have that status fulfilled.

The long-term impacts of Erdogan’s foreign policy maneuvers are unknown – and are perhaps dependent on how long he runs the show and what his successor does. But it could, as Sinan Ulgen argues to Euronews, simply end up isolating the country further, leaving it with haphazard partnerships. In short, even if Erdogan wishes to rebuild the old powerhouse, he could be constrained in that even allies approach this as anathema to their own aspirations. Furthermore, increasing tensions with NATO and EU allies could lead to greater talks about further distancing from Turkey. And as good of a friend as Putin seems, fault lines abound. Strong divergence already fosters relative exclusion from NATO’s grand goals. Turkey thus provides a model for international alliances in how to deal with such challenges – think the EU and Viktor Orbán’s Hungary.

While Erdogan is not Turkey, he likely will lead it for the foreseeable future. Continued negotiation and vigilance are thus required to constrain the worst of Ankara’s agenda, while retaining the stability of a necessary alliance.