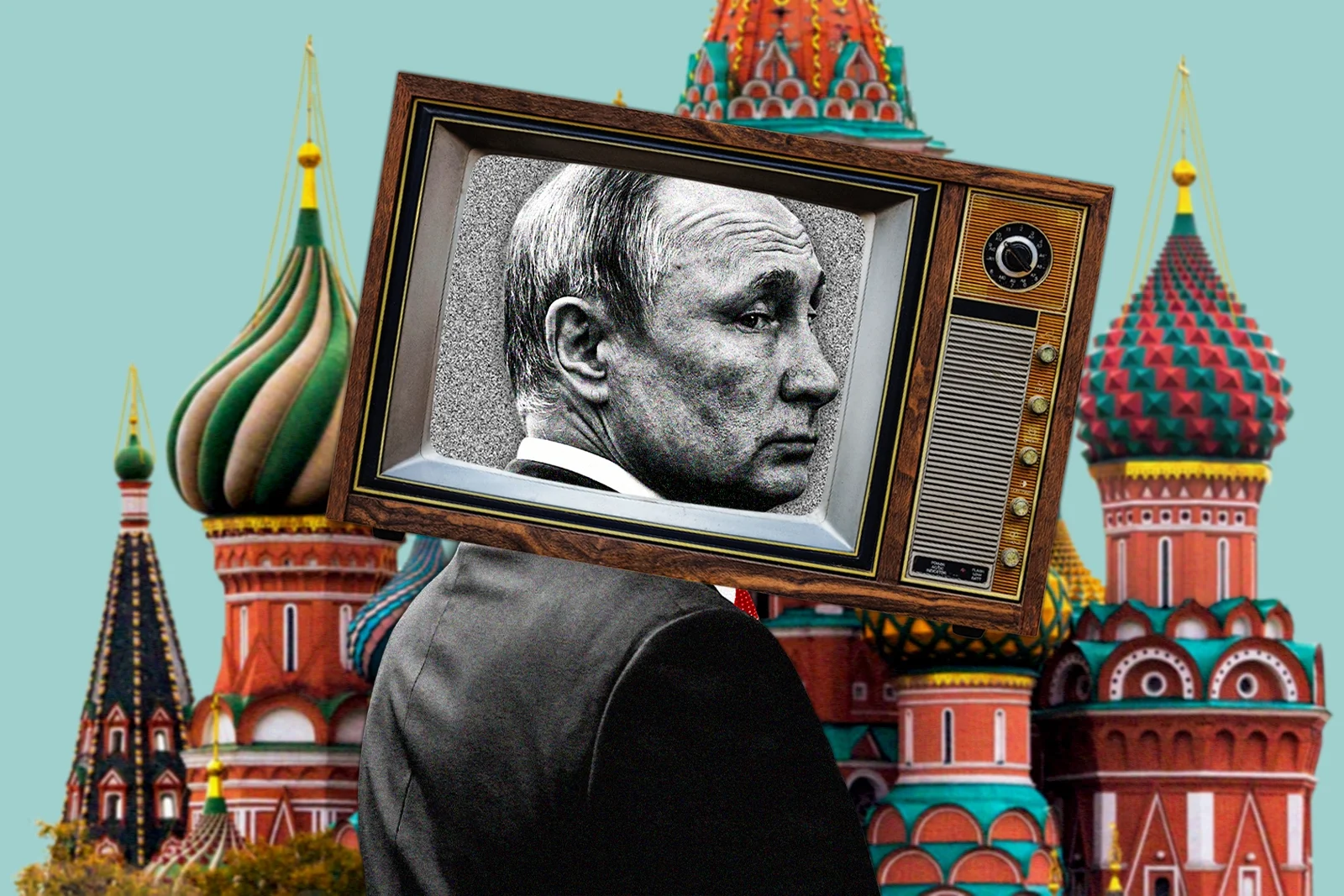

Ukraine’s Information War: Valeria Kovtun on Countering Russian Disinformation

Valeria Kovtun is a Ukrainian media specialist and the founder of Filter, Ukraine’s first government-backed media literacy initiative. She has collaborated with global organizations, including the Zinc Network, IREX, OSCE, and UNDP, to combat disinformation and promote critical thinking. Her editorial and production experience spans major outlets such as BBC Reel, Radio Free Europe/Liberty, and Ukrainian National TV.

Currently, Kovtun works with the OpenMinds Institute, a cognitive defense agency dedicated to analyzing emerging threats, conducting research, and executing counter-influence operations.

A Chevening scholar, she earned an MSc in Media and Communications Governance from the London School of Economics. Her research explores the dynamics of international propaganda, with a particular interest in the role of humor as a tool against disinformation.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: How did you become interested in media and propaganda?

Valeria Kovtun: I started in journalism because I was particularly interested in human behaviour—how people think, why they act the way they do, and how I could support those struggling with certain issues. After working in journalism, I joined the BBC, which had always been my dream. Most journalism students in Ukraine are taught that the BBC is the gold standard, but theory can differ from reality.

I always wanted to experience it in real life. Once I worked at the BBC, I realized there was much more to explore. Journalism was not the only profession I wanted to pursue; I had an entire world of opportunities.

After studying governance at LSE, I naturally progressed to policy. That’s why I returned to Ukraine after my time in London—to launch a national media literacy project. Today, Filter is a well-recognized institution in Ukraine, coordinating efforts to educate people about misinformation.

Of course, during the full-scale invasion, our work shifted from policy to more immediate, action-driven solutions. Everything became much faster-paced, which accelerated our growth. At the same time, it became difficult to maintain a singular focus. Instead of just educating people about misinformation, we had to actively combat disinformation itself—proactively responding to Russian propaganda circulating within Ukraine and abroad, which sought to undermine support for our country.

As a result, I transitioned into advocacy, helping explain to the world how propaganda works. Ukraine found itself at the forefront of an extremely aggressive information war, facing an avalanche of fake stories on various platforms and within local communities. We experienced all of this firsthand on the ground.

Obviously, if you have lived experience, you know I was encircled. I spent a few weeks in a very dangerous area, witnessing firsthand how fake stories spread throughout the environment and how lost people felt when faced with hundreds of local chat groups, but with little understanding of which ones were telling the truth.

When you have to make quick decisions to save your life or the lives of your loved ones, knowing where the truth lies, how to verify information, and which sources to trust is not just essential—it is paramount for survival.

That experience gave me firsthand insight. I understood the tactics behind disinformation, I knew how Russian propaganda operated, and at the same time, I was deeply involved in policymaking. Having all these perspectives allowed me to effectively address various communities—from policymakers to the general public—explaining why we need to act proactively, what steps we must take to protect ourselves from aggressive disinformation campaigns, and how we can build resilient societies capable of identifying and resisting propaganda in critical moments.

Jacobsen: Let’s talk about humor. It has long been a tool for undermining illegitimate institutions, exposing moral hypocrisy, and challenging authority. Despite its potency, it’s often dismissed as lightweight—perhaps because it can be silly or irreverent. Yet, in the context of disinformation and propaganda, humor can be remarkably effective. How do you use it in this fight?

I can offer a personal example. In the early days of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a now largely abandoned Kremlin talking point made the rounds in North American media. The claim? Ukraine was overrun by neo-Nazis—so much so that it was supposedly led by a so-called “Jewish neo-Nazi,” an absurd reference to President Zelensky himself.

I remember thinking: Zelensky is a former comedian, so this had to be one of the greatest setups for a joke in history—courtesy of the Kremlin—followed by the ultimate punchline: his very existence. The sheer contradiction of a “Jewish neo-Nazi” was so self-defeating that the narrative quickly collapsed.

Humor thrives on juxtaposition, on exposing contradictions. Given your work in media literacy and counter-disinformation, how do you employ humor to challenge international propaganda?

Kovtun: We are witnessing a significant shift in the information environment. Traditional democratic approaches—such as presenting verified information and offering a balance of perspectives—no longer capture the public’s interest.

Instead, we see that individuals with charisma, who appeal to emotions, are dominating the political landscape. There is a growing demand from societies worldwide for content that resonates emotionally, prompting them to act based on feelings rather than facts.

The same applies to humour. I have encountered countless articles, long-form texts, and in-depth investigations that aim to debunk specific misinformation or disinformation. But the challenge is that debunking takes time. You must thoroughly research, gather facts, and construct solid arguments to prove that a particular disinformation is false.

By the time you publish an article or investigative report, most people have already been exposed to the disinformation itself. And because they process information emotionally, convincing them after the fact becomes much harder. People remember what they first see, even if they scrolled past it.

Disinformation is usually emotional and appealing and can be subconsciously remembered. Once it is mentioned elsewhere, people tend to believe it even more. This is the problem with traditional debunking.

And what does humour do? Humour appeals to emotions. If you ridicule someone spreading a fake story, you evoke a positive emotion in the audience. That makes them more likely to remember your rebuttal.

It does not always have to be rational. It does not always have to be fact-based. The facts can come later. But the first thing you do is evoke emotion. And what is the most common emotional response? Laughter.

You laugh. You experience something positive—especially when there is an avalanche of negative news, which most people would rather avoid. But people are more inclined to pause and engage when something brings positivity. That is how humour works.

However, using humour effectively does not require extensive strategizing. Humour is often intuitive. Most of the time, the best jokes come to us when we are not thinking about them. We do not have to sit down and list all the potential ideas.

We do not need to brainstorm endlessly. Humour often emerges naturally from our lived experiences.

The same was true for Ukrainians in 2022. There was an incredible amount of energy within communities in Ukraine. There was resilience. There was unity. That collective spirit fueled humour and helped ridicule Russian propaganda. It also created viral stories of resilience—like the tale of an elderly Ukrainian woman knocking down a drone with a jar of tomatoes. Many of these stories were semi-true, semi-fictional. But they boosted morale at a crucial time.

Now, nearly three years after the war began, it has become harder to maintain that same level of positivity. When people constantly face existential threats, never knowing when their town might be hit or whether they will be safe the next day, humour becomes more difficult to sustain.

Humour was a powerful tool. But today, due to continuous threats and the sheer emotional toll, it is much harder for Ukrainians to create jokes that resonate with millions of people worldwide. So, going back to your question—humour works. But what works even better is developing our narratives.

If you analyze Russian propaganda, you will notice a pattern in how they communicate. Their messaging is extremely simple. It consists of short sentences, strong, active verbs, and no passive voice. It is highly emotional. It appeals to people’s most basic needs. And it is always repetitive.

If you look at Russian state media, Ukrainian Telegram channels that spread Russian propaganda, or even prominent Kremlin-aligned figures in the U.S.—such as Tucker Carlson—you will see that their messaging follows the same formula: the fewer details, the better.

In 2022, we discovered several Telegram channels operated by Russian accounts designed to spread disinformation in Ukraine. Within those channels, they even shared internal guidelines on how to create fake news.

The core rules were clear: Keep it simple, repeat as often as possible, and avoid unnecessary details—except for one or two to add credibility.

It is a marketing technique. When marketers promote a product, they use the exact same approach.

That is what we need to do as well. We do not have to debunk every piece of disinformation that circulates. Instead, we need to focus on telling our own story—who we are as a nation and what we are fighting for.

If we say, “We are fighting for democracy,” what does that even mean? How can people feel that? What is the tangible result of living in a democracy? Russian propaganda is effective because it simplifies concepts and makes them emotional.

We must counter it by crafting equally clear and emotionally compelling narratives.

They frame it in a way that suggests we are abandoning our traditional values. They present Russia as the key guardian of traditional Orthodoxy and family values.

This is something an ordinary person can immediately imagine. You do not need to think abstractly about liberty or freedom of speech—especially if you take those rights for granted. These concepts may not resonate as strongly. But when something is tangible and easy to picture, propaganda becomes effective. That is how Russian disinformation works.

In response, simply debunking it by saying, “Oh no, no, this is not what Russia means; let me explain,” and then overwhelming people with hundreds of facts does not work. The human brain is not wired to absorb massive amounts of raw information. It is wired to process stories, to internalize them, and to apply them to real-life experiences.

This is why humour can be a powerful instrument.

Jacobsen: What ideological movements or identity-based politics are most amplified in social media disinformation?

Kovtun: One of the defining characteristics of modern propaganda is how fragmented it has become. Tailoring content to very niche communities, even sub-identities is much easier.

For example, on platforms like TikTok, there has been an increase in propaganda content specifically targeting widows of Ukrainian soldiers. The war has created this distinct community—people bound by shared grief, sadness, and the search for support or validation from each other or the state.

Another example would be mothers, sisters, and wives of soldiers who have gone missing. These women have no idea where their loved ones are—whether they are alive or not. They are living in fear, clinging to the hope that their loved ones may still be alive, and desperately searching for any information.

By exploiting their vulnerability, propaganda and disinformation can effectively manipulate these specific groups. When I talk about fragmentation, I mean that with AI and digital tools becoming cheaper and more accessible, creating and disseminating targeted content has become significantly easier. This makes propaganda more precise and allows it to tap into the specific pain points of different communities.

In Ukraine, this is evident. If we look at Latin America, we see the same pattern. Previously, major Russian-backed media outlets like Russia Today (RT) and other state-controlled groups had a strong presence. However, since many Western democratic countries have banned them, Russia has adapted.

Now, they localize their efforts. Instead of relying on large, recognizable media outlets, they create smaller, localized news sources that blend truth with disinformation. These sources legitimately report on local issues, making their narratives harder to detect.

Over time, through a cohesive, sustained effort, they introduce geopolitical narratives that favour authoritarian regimes and undermine democratic institutions. So, regarding ideologies, propaganda today is highly tailored to different communities.

The overarching goal is to promote authoritarianism. How it is executed depends on the local context. For instance, anti-U.S. sentiment is a powerful entry point in many Latin American and African countries. Any message that aligns with anti-Western rhetoric is more likely to be accepted. Once that foundation is laid, additional disinformation can be built on top with much less resistance.

Jacobsen: How do Russian and other propaganda sources frame narratives for domestic audiences versus international audiences? And also, when exporting propaganda, do they adjust their messaging for different regions?

Kovtun: The short answer is yes. Russian propaganda has been shaping narratives for domestic audiences for decades. This means the Kremlin already has a fertile ground for circulating long-established talking points.

What I mean by fertile ground is that, for many years, the Kremlin has systematically prepared its population for events like the invasion of Ukraine. One way they have done this is by suppressing any potential political opposition.

For instance, a major tactic has been ensuring that educated citizens—those with university degrees and knowledge of foreign languages—become apolitical. How do they achieve that? By creating a climate of distrust.

They make sure that people believe no one can be trusted. Even if someone recognizes that Russian state media is corrupt, they are also conditioned to distrust Western media, such as the BBC or other foreign outlets.

When people are unsure who to trust, they withdraw from political engagement altogether. They stop questioning, seeking alternative viewpoints, shutting down, and avoiding thinking about politics.

So, the Kremlin has deliberately eroded personal agency in many individuals who might have become political dissenters.

This is why, today, we see millions of Russians reluctant to speak out—not because they are all loyal to the Kremlin, but because they have been conditioned into passivity over many years.

This did not happen overnight. It was a long-term strategy. For international audiences, the Kremlin takes a localized approach to propaganda. For example, we now see a growing presence of Russian-backed media sources designed specifically for local audiences in Africa.

Interestingly, democratic institutions often overlook entertainment platforms, but Russian propaganda finds its largest audiences precisely there. A fascinating case involved a troll factory in St. Petersburg, where they had an entire specialized unit dedicated to producing astrology websites and horoscopes.

At first glance, it seems unrelated to geopolitics. However, these seemingly innocent platforms were used to subtly introduce and reinforce Kremlin-friendly narratives—gradually shaping public perception in a way that people would not immediately recognize as propaganda.

This was not just speculation—it was proven when a journalist went undercover and worked inside the troll factory for some time.

One journalist who worked at the troll factory was in charge of a special project for which she was tasked with creating a fictional persona named Contadora. Contadora was presented as a spiritual leader, and her content mixed personal stories with geopolitical narratives.

For example, in one story, she talks about her sister living in Germany and describes having a bad dream in which her sister was taken by dark forces. She then interpreted the dream as a warning—suggesting that Germany was too dependent on the U.S. and vulnerable to American influence. This is just one small example.

But imagine if most African entertainment platforms featured similar astrologers and spiritual leaders embedding subtle political messaging. And this is not just happening in Africa.

If you look at global trends, there has been a significant rise in belief in the paranormal, mysticism, and spirituality—especially among Gen Z. For instance, the #TarotReading hashtag has attracted millions of views on TikTok.

Within these tarot and astrology videos, we have seen cases—especially in France and Germany—where certain tarot readers subtly introduce geopolitical narratives to their audiences.

This is just one example of how propaganda adapts to digital culture. And yet, in democratic societies, where we enjoy freedom of speech and open dialogue, Russian propaganda can easily integrate into various platforms and find creative ways to spread its messages.

Meanwhile, democracies are often disadvantaged because ethical considerations bind them. They worry about the best way to communicate narratives without crossing ethical boundaries.

Because of this fundamental difference in governance, democratic societies will always face certain limitations in their response strategies. That is why I encourage my partners in the EU to think outside the box—not just focus on discussions within our own bubble but be more creative in how we counter disinformation.

Humour could be one approach to promoting democratic narratives. But I am sure there are many more innovative strategies we have not even explored yet.

Jacobsen: Valeria, thank you for your time today. I appreciate it.

Kovtun: Thank you. Let me know if you have any questions or if you need clarification on anything. I’m happy to help.

Jacobsen: Excellent. Thank you so much.