UN Security Officer’s Ivory Trafficking Conviction Opens Pandora’s Box of Queries

In the shadowy world of ivory trafficking, akin to the narco trade, the stature of the accused is often gauged by the volume of the contraband or the prestige of their legal representation. By such a barometer, Kenya has adjudged a case of seminal importance.

On October 23, within the dual-purpose confines of an office and courtroom at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) in Nairobi, Handrianus Theodore Putra, an Indonesian national with duties as a UN security officer, was convicted and sentenced for possessing and intending to distribute 38.4 kilograms of elephant ivory. His journey, originating from Bangui in the Central African Republic with the endpoint envisaged as Jakarta, Indonesia, encountered an abrupt halt in Nairobi.

Putra, however, diverged from the archetype of an inconspicuous ‘mule’ or an oblivious traveler ensnared with ivory, despite his assertions of ignorance.

Following his arrest on October 17, Putra appeared at the JKIA law court for mitigation arguments predicated on his guilty plea, accompanied by an entourage of six attorneys. The lead counsel, the high-profile advocate Danstan Omari, has represented Fred Matiang’i, the ex-Cabinet Secretary for the Ministry of the Interior, and was presently representing televangelist Ezekiel Odero, a wealthy Kenyan pastor accused of killing 400 of his followers. Omari was also recently short-listed to fill the vacant role of Director of Public Prosecutions for Kenya. Putra’s legal team was supported by two other experienced lawyers from Nairobi area law firms.

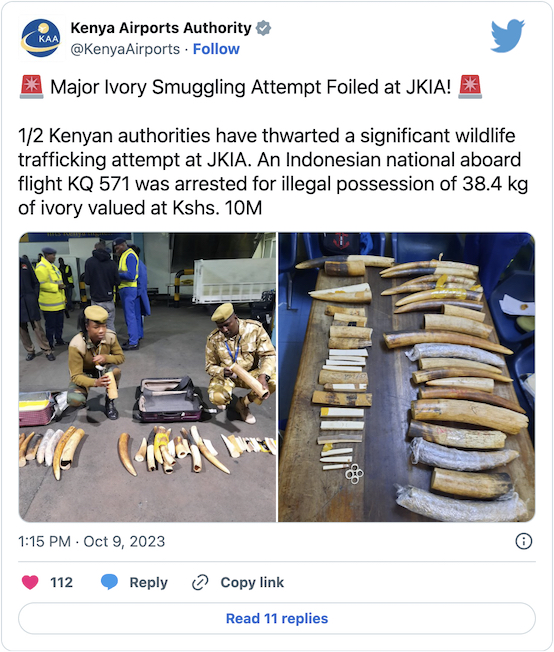

The local media initially broke the news of Putra’s arrest, an alert that originated not from law enforcement but through a press release from the Kenya Airport Authority (KAA). They reported: “The vigilant Kenya Airports Authority (KAA) security team at Terminal 1 C discovered the illicit cargo during mandatory passenger screening.” The accompanying visuals displayed KWS personnel alongside the seized luggage containing 23 tusk pieces, 18 worked ivory pieces, and 4 rings. The two pieces of Putra’s luggage were found to contain 19.6 kg and 18.8 kg of ivory respectively. Notably absent was the disclosure of his final destination, and his name was curiously omitted from national media reports.

Subsequent revelations in the courtroom shed light on the saga. The prosecution, addressing Senior Resident Magistrate Renee K. Kitagwa, outlined the sequence of events culminating in Putra’s arrest. Detected by vigilant airport security, leading to his arrest by JKIA police, identity confirmation through his passport, UN security identity card, and boarding pass, and the subsequent confiscation of the ivory by the Kenya Wildlife Service. The ivory’s display in court underscored the gravitas of the offense.

Omari opened the defense’s arguments. He began by telling the court that his client had wanted initially to plead not guilty. Omari and the defense team, however, advised Putra that due to stringent Kenyan wildlife crime laws that were recently enacted (certainly subjective), he would be better advised to change his plea.

Omari did not add that there were other advantages to a guilty plea. First of all, a guilty plea would likely cap any further investigation, important if this was an organized crime. Secondly, a guilty plea allows the facts of the case to be read into court by the overworked prosecutor, who while having many other cases to handle, may only remember the basic facts thereby translating into a lighter sentence.

Omari stated before the court that his client, Putra, an Indonesian police officer and a UN security officer in the Central African Republic, was arrested while transitioning flights. At that time, Putra was moving from a Kenya Airways flight from Bangui to Nairobi to a Qatar Airways flight bound for Jakarta, Indonesia. The defense explained that the ivory found in Putra’s possession was intended as a traditional dowry gift, in line with his cultural practices. Omari contended that the ivory trade is not illegal in the Central African Republic—a claim that is incorrect—and asserted that Putra was unaware that he was breaking any laws. Moreover, Omari argued that Putra had not planned to pass through Nairobi or its international airport. He highlighted that the ivory, placed openly in a polythene bag within the baggage, was not concealed, suggesting no attempt at smuggling by the accused.

Omari introduced two observers to the court, one being the head of Criminal Investigations in Indonesia and the other a colleague.

The defense team presented a unified argument in mitigation: their client, an exemplary police officer subject to thorough vetting for his current role, was unwittingly caught in an unfortunate situation. They emphasized his lack of prior offenses, his ignorance of the law regarding his actions, and his profound regret. They proposed that, given these factors, deportation coupled with a potential fine would be a fitting sentence. The proceedings took a turn when the sixth defense attorney was precluded from speaking by Magistrate Kitagwa, who decided that the testimony presented was sufficient.

The defense arguments went uncontested, though some points were incorrect. Transporting ivory out of the Central African Republic requires a CITES permit, an international agreement ensuring the survival of endangered species amid global trade. In Indonesia, ivory trafficking is illegal under Law No. 5/1990 and Article 55 of the Criminal Code, punishable by up to 5 years in jail or a fine of about $6,500.

Putra’s claim, relayed solely by his attorney, that he did not intend to transit through Nairobi, was baseless, given the current travel protocols.

As far as Omari’s claim regarding Kenya’s stringent wildlife crime laws, one wonders if Putra was aware that the typical sentence to come out of the law court at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport over the past 6 years has been a fine of $6,500 or in default one year in jail. The lone exception was the case of Chinese national, Cao Juano, who was arrested in July 2017 with 120 kilograms of ivory as she was transiting to Hanoi from Zimbabwe. She was fined $40,000 or in default, one year in jail. She had been in custody for seven months at the time of sentencing which was included as time served.

Despite the defense’s narrative and the ‘ivory as dowry’ claim, Magistrate Kitagwa seemed unconvinced. Six days later, on August 23, in a scarcely attended courtroom, with only a clerk at her side, Omari, the accused, and a representative of the Indonesian government present, she pronounced the sentence. On the charge of Dealing in Wildlife Trophies, Putra was fined $20,000, or in default 7 years imprisonment, and for Possession of Wildlife Trophies, Putra received another fine of $20,000, or in default 5 years imprisonment. The sentences were to run concurrently, meaning that both sentences would run together simultaneously with 7 years being the longest serving term in a Kenya prison. The following day, Putra was on a flight out of Kenya.

The court faces a dilemma in setting fines that are both fair and deterrent. Wealthy criminals or those linked to organized crime may see fines as a mere cost of doing business. The circumstances suggest that Putra’s case might involve more than a mere cultural misunderstanding.

Contrastingly, three individuals were recently sentenced to 10 years without a fine for transporting a much smaller amount of ivory, showing an inconsistency in sentencing.

Perhaps surprisingly, despite the initial media interest in Putra’s arrest, there was no coverage of the conviction and sentencing. The lone outsider to the proceedings was a representative from SEEJ-AFRICA, a small organization that follows ivory prosecutions in Kenya. They were approached and asked what it would take to not publish their report. Were other media outlets asked the same?

The case prompts several inquiries: Have preventative lessons been assimilated and disseminated to avoid future infractions? Will the airports and agencies involved collaborate to exchange critical information and intelligence?

The baffling security lapse that allowed two suitcases, each laden with nearly 20 kilograms of unmistakable elephant ivory, to slip through x-ray scanners and security measures demands scrutiny. It’s unclear at which point in the journey this oversight occurred, especially since the flight included a layover in Douala, Cameroon, and the arrest happened at Kenya’s international airport only three hours post-arrival, moments before the connecting Qatar Airlines flight. This raises the possibility that Putra was not on the Bangui-Nairobi flight as assumed, or that the ivory was handed to him at Kenya’s international airport. The integrity of baggage handlers at the implicated airports is in question, as is whether Putra’s United Nations identification was misused to evade security checks.

Further, his travel history could shed light on his activities, and the claim—propagated solely by his attorney, Danstan Omari—that he had no knowledge of passing through Kenya’s international airport, is patently false and implausible for anyone familiar with international travel. This claim may simply stem from a miscommunication.

Perhaps the essence of all these questions could be answered by just one. Who actually paid the invoices for the most important ivory trafficker in Kenyan history?