Will’s Core Canon: How ‘In the Loop’ Became the Most Adept Political Satire Film of the 21st Century

Welcome to Will’s Core Canon, a series covering some of my all-time favorite movies and why they work. This series seeks to go beyond surface-level analysis to strike at the core of why these films resonated the way they did.

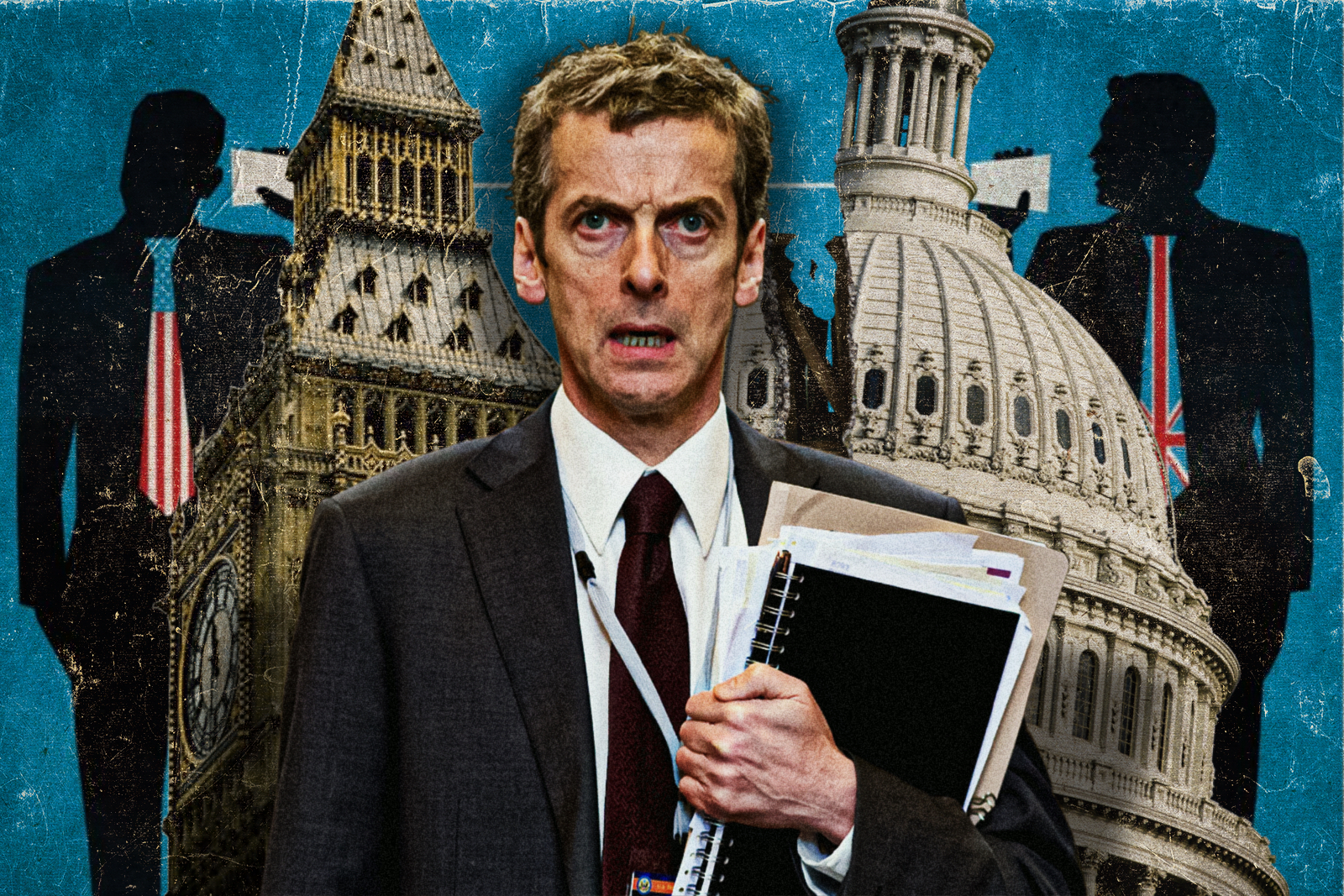

In one of the opening scenes of Armando Iannucci’s 2009 British comedy In the Loop, we see Malcolm Tucker (Peter Capaldi) berating someone as he walks and talks with them on a cell phone that unexpectedly dates the film despite it just being a little over a decade old at this point. The so-called “walk and talk,” where characters spout exposition while walking, had been a then-current staple in popular culture owing to its frequent appearance in the television writing of Aaron Sorkin, particularly on The West Wing.

But unlike Sorkin’s characters, this isn’t a government advisor updating a world leader at a pivotal point with a massive strategic impact. This is a foul-mouthed Scotsman, and the prime minister’s communications director, threatening a reporter he is calling in hilarious detail: “Listen, see when I tell your wife about you and Angela Heaney at the Blackpool conference, what would be best? An email, a phone call, what? Hey! I could write it on a cake with those little silver balls: ‘Your hack husband betrayed you on October the 4th and congratulations on the new baby.’ Yeah, maybe it’s better to spike it.” He closes this with a phrase that has become beloved to me: “Yeah, okay, fuckity-bye!”

In the Loop is a movie that defies expectations in a lot of different ways. It is technically based on a TV show, but it doesn’t require that you’ve seen the show before you watch it. In that way, it is more like when the character of Borat made the leap to the big screen after Sacha Baron Cohen’s success on Da Ali G Show than it is like a TV-to-movie adaptation heavy with series lore and mythos that ties into the established canon, like 1998’s The X-Files: Fight the Future or even 1998’s The Rugrats Movie.

The show in question is The Thick of It, a BBC political sitcom in which the character of Tucker originated. Much of the cast of In the Loop also stars in The Thick of It, albeit in different roles, with only Malcolm Tucker carried over. The Thick of It ran for 23 episodes over four seasons from 2005 to 2012. I’ve seen a bit of the show, and I think it’s fine. It’s able to elicit a belly laugh or two, but its references and sensibilities feel much more attuned to a British audience. Show creator Armando Iannucci, who also directed and co-wrote In the Loop, would find his greatest success with the highly acclaimed HBO political comedy series Veep starring Julia Louis-Dreyfus as a flustered vice president-turned-commander-in-chief, which I think is a much stronger series.

But Iannucci’s masterwork might just be this movie. It involves an upcoming war in the Middle East that’s been all but declared, because lest we forget, it’s 2009, and Iraq and Afghanistan are at the forefront of political discussion and geopolitical entanglements. The incompetent British cabinet secretary Simon Foster, played by British film and TV mainstay Tom Hollander, gets wrapped up in a situation beyond his control when he says during a radio interview that he thinks war is “unforeseeable.” This happens to correspond with the first day on the new job for Toby (Chris Addison) as Foster’s special advisor. Tucker dismisses Toby by calling him “Ron Weasley” or “fetus boy” at various points throughout the film.

And then there’s the American delegation in London to discuss the impending war with their British allies. U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Diplomacy Karen Clark (Mimi Kennedy) is fervently anti-war, while her overwhelmed, long-suffering assistant Liza (Anna Chlumsky, best known to 90s kids as the titular girl in My Girl and eventually picked by Iannucci for a major role on Veep) compiles a document arguing against the war that becomes well-known in diplomatic circles.

It is the interplay between the Brits and the Americans that strikes at the heart of the film, why it’s so hilarious and resonates so much. Foster, Tucker, and Toby eventually have to make a trip to Washington, and as a DC native, this is easily some of my favorite comedy in the film. Of particular note is what Tucker says to the young White House intern he meets with instead of the higher-ranking and older official he was expecting: “Don’t get sarcastic with me, son. We burned this tight-arsed city to the ground in 1814, and I’m all for doing it again starting with you, you frat fuck!” Liza also notes that Capitol Hill staffers love to let loose at intense metal and punk concerts, which might come as a surprising revelation for those who didn’t live in or around the nation’s capital.

While in Washington, the British delegation must not only contend with Clark and Liza but also U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Policy Linton Barwick (David Rasche), who keeps making strange comments like “All roads lead to Munich!” and “In the land of truth, the man with one fact is the king.” There’s also the anti-war Lt. Gen. George Miller, played by the late, great James Gandolfini in one of his best non-Tony Soprano roles ever. He says of war that “once you’ve been there, once you’ve seen it, you never want to go again unless you absolutely fucking have to. It’s like France.” Tucker eventually dubs him “General Flintstone.”

All the while, there’s junior staffer Chad (Zach Woods, best known for his roles as Gabe on The Office and as Jared on Silicon Valley), frequently feuding with Liza and trying desperately to be noticed by either Barwick or Miller. Clark eventually dubs Chad and Miller to be “General Shrek and his faithful talking donkey.” Chad has, to me as an only child, easily one of the best lines of the movie after Liza calls him out on his similar status: “I gotta say, I don’t understand how my parents’ limited reproductive ability reflects badly on me. I’m the sperm that made it!”

The stakes of the film feel as if they keep expanding: the local politics of the UK give way to foreign relations with a key ally in Washington, and soon, our cast of characters find themselves at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, hobnobbing with diplomats and representatives from every country on Earth. But the film reiterates the theme that all politics is local. Simon is ultimately dethroned as a Member of Parliament when a garden wall collapse in his home constituency gets covered as a major blunder by the news media. It all feels so fickle, but such is the nature of politics.

The film received some attention when it was first released, most notably garnering a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay at the Oscars that year. But, as the cast and creators have become better known for other projects, including Veep but also Capaldi’s three-season tenure as Doctor Who, so has the movie. In the Loop came out at an awkward time, right at the transition from George Bush to Barack Obama, when it felt like every other non-American country was dogpiling how stupidly they thought the U.S. had acted in the decade following 9/11 throughout publications and the media in general.

As much as it pains me to say it now, my first reaction to the movie was one of begrudging amusement. Overall, it just felt to me, as someone addicted to watching Jon Stewart’s edition of The Daily Show, as making a lot of the same points as Stewart did on a nightly basis: Boy, the U.S. government sure is full of stupid people! Boy, the UK was sure complicit in a lot of America’s warmongering! Boy, the UN is pretty useless, ain’t it?

However, the film’s ultimate success is how well the characters stand out. From the incompetency of Simon Foster to Toby having not only to deal with geopolitical consequences but a breakup as a result of him being unfaithful to his girlfriend Suzy (Olivia Poulet) while in Washington, they feel feeble and not up to the task, which the film wants to stress is definitely the case.

The character of Malcolm Tucker in particular benefits from repeat viewings. I sympathize more with him in the immediate aftermath of a scene when he has been humbled and humiliated by Linton Barwick. Like any great character arc, he’s temporarily lost his powers of manipulation, able to insult whatever he wants to happen into existence. When he is eventually able to recover, the verbal lashing he gives Barwick is a highlight of the film.

Some of the greatest comedies of all time involve this sort of above-it-all mocking of politics: the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. I feel like In the Loop follows in that great tradition, pointing out the dry Britishness of their system, while finding time to poke fun at those crazy Yanks, living in a country they’re convinced is run by literal children: “It’s like Bugsy Malone, but with real guns,” one character comments at one point. The movie is also one of the funniest I’ve ever seen. Repeat viewings have me picking up on lines and jokes I didn’t catch previously, as well as laughing at memorable moments I already had countless times before.

So, if you haven’t already, check out this incredible comedy, this adept political satire, and this wonderful spoof of the Transatlantic relationship. And while the cast and writers seem to have moved onto bigger and better things, for the past couple of years, I’ve quietly hoped for a sequel where this cast is forced to deal with the biggest political blunder of recent times on their side of the pond: Brexit. Even Malcolm Tucker doesn’t have the language to describe what a clusterfuck that ended up being.