Will’s Core Canon: How the Pulp Imagery of ‘RoboCop’ Defined the 80s and Influenced the Future

Welcome to Will’s Core Canon, a new series covering some of my all-time favorite movies and why they work. This series seeks to go beyond surface-level analysis to strike at the core of why these films resonated the way they did.

When director Paul Verhoeven was first offered the chance to direct a science fiction project based around a spec script called RoboCop, he immediately dismissed the opportunity. He had never really liked sci-fi as a genre, and had already made successful movies in his native Netherlands, and was looking for what would be his first Hollywood production.

The story goes that he read the first page and threw the script away. “I thought it was extremely silly and stupid,” he recounted years later in a wonderful making-of documentary called Flesh and Steel: The Making of Robocop. “I threw it on the floor, and said ‘I’m not going to shoot this kind of rubbish.’” It was only after his wife pleaded with him to give the story a chance after she had read it herself, telling him that at its core, the movie is about someone losing their identity. It is, and so much more.

Verhoeven claims there were two classic sci-fi movies that most informed his 1987 blockbuster. One was the 1927 German film Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang. Lang’s vision is an unnerving but compelling one, a dystopia where class differences can’t be ignored, where a robot woman is made to emulate her real human counterpart to keep the oppressed masses complicit until she decides to bring chaos instead. Even now, almost a century after its debut, Metropolis resonates, and its imagery has impacted almost every conceivable part of popular culture.

The other influence was The Day the Earth Stood Still, directed by Robert Wise. A cautionary tale, The Day the Earth Stood Still is about Klaatu (Michael Rennie), an extraterrestrial who brings a message to the people of Earth advocating for peace rather than suffer nuclear annihilation. One can certainly see aesthetic influences, particularly of Gort, Klaatu’s iconic robot, on the design of RoboCop. But when I think of the imagery of The Day the Earth Stood Still, I think of awe and reverence. Certainly, what became some of the iconic hero shots in RoboCop owe a great debt to how Gort was depicted in that film.

Metropolis depicts a world on the edge, and there’s a constant feeling like some sort of cataclysm is imminent, how appropriate for a film from Germany in the 1920s. Released in 1951, The Day the Earth Stood Still is about an anxious world seeking a sign from above, how appropriate for a film from the 1950s dealing with the post-WWII, now-nuclear Cold War reality. Both of these classic science fiction films encapsulate the times they were made in, and address concerns about the present and the uncertainty of the future. In this way, they are both also like RoboCop.

RoboCop is a movie about excess, the need for everything to be big, to be loud, to make a scene. It rings of 1980s America, summarizing everything good and bad about the Reagan-dominated decade. The bad guys’ weapons explode bigger than anyone else’s. Even one of the movie’s more likable characters does enough cocaine to make Tony Montana blush. The film’s score by Basil Poledouris is boisterous and victorious. But the film also addresses a certain anxiety, an uncertainty about the future: “Is this where we’re headed?” It features in-film media breaks featuring talking heads babbling about news headlines and advertising big cars and violent family games in a way that not only feels prescient, but unnerving.

Robots were familiar territory in the 1980s. After all, by the time RoboCop premiered, Blade Runner (1982) and The Terminator (1984) had already been released and made waves. Even the adorable robot Johnny 5 from Short Circuit (1986) had endeared himself to the public by then. But RoboCop was different. It combined Blade Runner’s heady philosophical themes with the otherworldly aesthetic of the titular Terminator. It didn’t mind being self-indulgent fun, as demonstrated by the movie’s infamous violence and graphic gore. But after I experienced RoboCop stunningly restored on the big screen for the first time at a nearby Alamo Drafthouse, I realized that the movie is more than the sum of its parts. However, each of its parts works perfectly in conjunction to create one of the best and most memorable American science fiction movies ever made.

RoboCop tells the story of Alex Murphy (Peter Weller), a police officer in a futuristic Detroit who gets gunned down by a gang run by the evil Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith, best known today as Red Forman on That ‘70s Show). What’s left of Murphy is used to build the cybernetic RoboCop, who serves the public trust, protects the innocent, and upholds the law. RoboCop was the brainchild of Bob Morton (the late Miguel Ferrer), an ambitious junior executive at Omni Consumer Products, or OCP. This causes him to come up against Dick Jones (Ronny Cox), the company’s senior president whose first name is very fitting as he is competing with Morton for the attention of the company’s CEO (the late Dan O’Herlihy). But Murphy’s former police partner, Officer Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen), confronts RoboCop and reminds him of his previous life, which leads to the cyborg himself questioning what exactly happened to him. As Jones and Boddicker scheme to finish off RoboCop once and for all, he and Lewis regroup for a climactic confrontation at the gang’s old hideout where Murphy was originally shot.

There’s another influence Verhoeven admitted had a profound effect on the movie: religion. Verhoeven saw RoboCop as very much a Christ figure, who dies and is reborn, who is rejected, physically punished, and humiliated by the people he was there to save, and who even can be seen appearing to almost walk on water at the film’s conclusion. “The figure of Jesus has always fascinated me,” Verhoeven admitted. “And the mythological narrative in the Gospels fascinates me, too…When I got the script, I started to realize that, in some way, RoboCop had something to do, at least for me, with Jesus…These themes of crucifixion, resurrection…at the end, [RoboCop] is an American Jesus who uses his gun.”

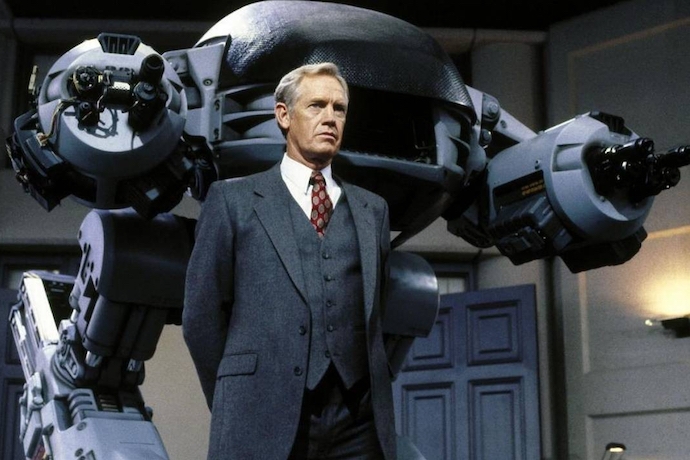

While I can only kind of see where he’s coming from regarding the messianic references, there is definitely a certain Americanness to the character: he protects Detroit, seen as the center of the American auto industry. He looks like his armor could just as easily be applied to a Pontiac, representing the ultimate merger of technology and legal authority. But, the movie revolves around RoboCop’s ultimately human nature, which distinguishes him from the other robots OCP has roaming the streets of Detroit. This includes the massive ED-209 machine that RoboCop fights throughout the film, and in one particularly memorable early sequence, accidentally annihilates an OCP employee in a spectacularly bloody fashion during a board meeting.

In an age when everyone loves to point out how much society is starting to resemble the one depicted in Idiocracy (2006) or how we’re starting to resemble the doughy, complacent spaceship residents as seen in WALL-E (2008), has there ever been six words in a movie that better depict how far society has fallen than “I’d buy that for a dollar”? The phrase is repeated throughout the film in a television broadcast that is shown to be very popular, yet seems lewd and lowest-common-denominator drivel. In 1987, it was the butt of a joke. Nowadays, is it any less weird than living in a world where Rudy Giuliani was on The Masked Singer?

I love little moments in this movie, like the warmth and tenderness RoboCop/Murphy and Lewis treat each other with, particularly before the film’s climax. “It’s really good to see you again, Murphy,” Lewis says upon seeing his entire face for the first time after he removed his helmet and visor. She reaches out to comfortingly touch his shoulder after he says he can’t remember his family, and he dismisses her. “Leave me alone,” he tells her. Later on, she supports him as he recalculates how to aim and fire his gun, and he thanks her. “Murphy, I’m a mess,” an injured Lewis tells RoboCop at the conclusion of their battle. “They’ll fix you, they fix everything,” he assures her.

Peter Weller plays RoboCop with the nuance the character deserves. Before this, he wasn’t much known for anything besides his role as the titular protagonist in the 1984 cult classic The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension. Likewise, Nancy Allen, who plays Lewis, was primarily known for playing teens in movies like Carrie (1976) and I Want to Hold Your Hand (1978), as well as her long strawberry blonde locks in contrast to the short haircut she sports in this movie. Their roles would end up being breakout, and even great character actors like Ronny Cox, already known for Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and who would collaborate with Verhoeven again for 1990s Total Recall, end up being disparagingly designated as “Dick from RoboCop” any time I see him pop up in another movie.

I think the secret to RoboCop’s success is that everyone underestimated it. It’s all in that title. Producer Jon Davison remarked “everybody had reservations about the title, because the title was just basically silly…So, we often thought about trying to come up with a better title, but it stuck.” Screenwriter Ed Neumeier recounted that Orion executives told him “we can never sell it with that title, it’s stupid, it sounds like a kids’ movie.” Personally, I can’t imagine this movie being called anything but RoboCop.

When those cinemagoers in 1987 went and saw a movie called RoboCop, I bet they had certain expectations based on that title alone. Certainly, a genre flick, but one that has its tongue in its cheek? Maybe they weren’t expecting the subversive, dark humor or the social satire. Apparently, many parents didn’t realize it was such a dark flick, putting RoboCop in the same league as Rambo and The Terminator as R-rated franchises from the 80s that made toys marketed to kids. RoboCop even had his own Saturday morning cartoon.

I can understand the character’s appeal to children: when you look at him, he’s neat-looking and you’re curious to see what he’s all about. He recalls some of America’s favorite imagery: the gun-slinging hero, the knight in shining armor, the order-restoring sheriff, bulletproof Superman. But the way the camera shoots the character in this movie brings to mind the covers of pulp literature or comic books: it pops, there is fluidity and energy to it.

That’s another way the movie makes you underestimate it: you think you’re going to get an action shootout with this impressive-looking character at its core, but you get deep themes of identity and transformation, an arguable condemnation of capitalism as a structural system, and sure enough, some of the best action ever captured on film. It’s easy to see why the film has endured for so long, and that Detroit will even install a statue dedicated to the character sometime in the near future. Its sequels and remake couldn’t capture what made it so great, because at the end of the day, what is RoboCop if not lightning in a bottle, or better yet, a cyborg?