Will the Khartoum Power–Sharing Agreement Survive?

What started the unrest in Sudan that finally led to Omar al-Bashir’s ouster in April of this year? The majority of news outlets have concentrated on economics as the dominant narrative. I argue that civil unrest in Sudan should be viewed as the result of interplay between economic and political factors ranging from lack of democracy, state repression, human rights violations, genocide in Darfur, Blue Nile, and Southern Kordofan, to endemic poverty and the looting of oil, gold and other economic resources by a tiny group of political elites.

The protest against Bashir’s regime began in the eastern city of Atbara due to increased bread prices, and later spread under the leadership of the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA). Soon afterward, government security forces attacked protesters in Khartoum, Omdurman, and other towns along with attacks on student protests in El Geneina, West Darfur, and many other places in the country. Hundreds of human rights activists, journalists including correspondents from Reuters and AFP, protesters, and opposition party members were detained and tortured in an effort at suppressing the pro-democracy movement. As the Doctor Central Committee reports on 28 July, at least 246 people were killed and 1,353 were injured since the outbreak of the protests. Bashir was forced out in April and charged with corruption and money laundering. It is still uncertain whether Bashir will be handed over to the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

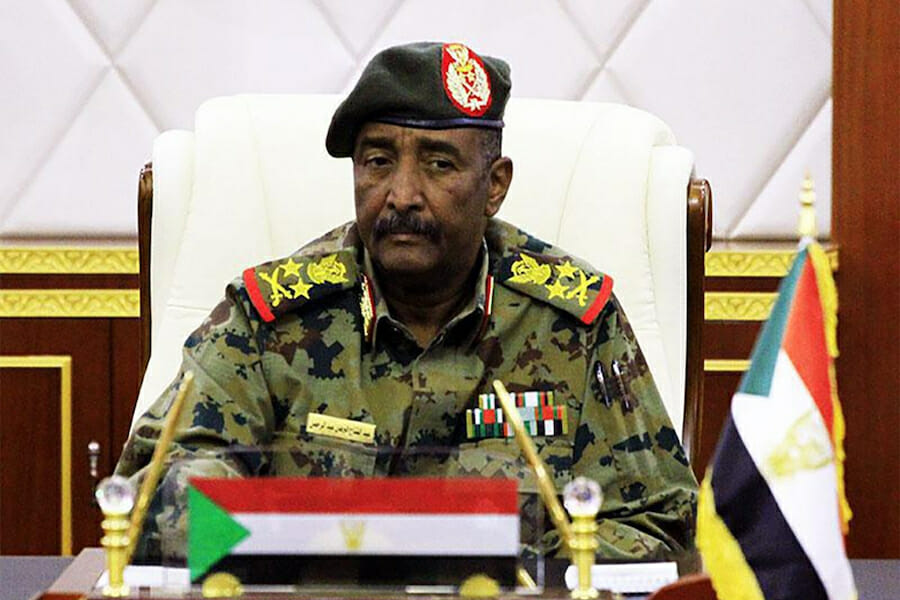

The seven-member Transitional Military Council (TMC), led by Lt. General Abdel Fattah Burhan, resumed power in April in the name of national unity. The junta opted to stay in power despite the use of force against civil protesters. This has been criticized by the international community. Under heavy pressure from the international community, the TMC was compelled to sign the Khartoum Power-Sharing Peace Agreement on July 17th with the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC).

The agreement is viewed by the Sudanese people, analysts, and international observers as the new beginning of a democratic Sudan. However, many Sudanese political parties and militia groups have raised questions of what kind of peace can be expected with many of Bashir’s strongmen still in charge.

Sudanese politician Suliman Arcua Minnawi, known as ‘Minni Minnawi,’ argues that “we will not allow the monopoly of opportunities at the expense of the 6 million displaced people and refugees, and we will not accept the practice of exclusion again. We will work for freedom, peace, and justice.” He also adds that “the next government will face opposition from the street and a real challenge in the pressing issues, as all members of the FFC will participate in the transition period with non-partisan signs and dormant cells.” This makes us cautious to say that we should not offer over-simplified explanations on the future of the Sudan power-sharing agreement since it has already been rejected by revolutionary social forces.

Omar El Degeir, the president of Sudanese Congress Party (SCP), and one of the leading figures in the FFC, told El Tayar newspapers that the FFC did not offer two seats in the Sovereign Council to the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF), a coalition of armed movements as per the Addis Ababa Agreement signed on 25 July 2019. The agreement has been criticized and rejected by the United Popular Front (UPF) and the National Forces Coordination, a coalition of right-wing Islamist groups mostly affiliated with Bashir’s regime. They have vowed to oppose the Sovereign Council labeling the power-sharing agreement as a bilateral agreement between the junta and the exclusive FFC. The people of Sudan have mixed responses about the agreement with a clear-cut division between pro-agreement and anti-agreement elements of the society.

The people from East Darfur in Khartoum are demonstrating for the release of Musa Hilal and other prisoners of the Janjaweed militia group. Apart from this, ethnic clashes in Port Sudan between Beni Amer tribesman and displaced Nuba from South Kordofan, the accusation of Darfur rebels against the RSF for killing people of three villages, and gun attacks on 67 farmers in the area of Abu Dalek in north Darfur, are just a few notable cases of Sudan’s post-conflict fragility. The major threat to the transition from anarchy to normalcy is the intra-government power-centric conflict as already manifested in the judiciary appointments made by FFC but blocked by the junta which was severely criticized by the Democratic Lawyers Association claiming that the junta has vested interests to recruit judges attached to the Bashir’s regime.

Another important issue is whether the transitional government is truly capable to investigate and punish criminals who were directly involved in killing protesters before and after 11 April 2019. Despite the fact that the Sovereign Council has expressed a commitment to form an independent investigation committee on human rights violations, the junta is responsible for dozens of deaths during the protests. Can the transitional government also end the decade-long religious persecution of Christian minorities by Bashir’s government?

From an academic point of view, I am reminded that many power-sharing peace agreements have failed across the globe before achieving their core objectives. The return to violence is inevitable if past war crimes and grievances of the society are not properly addressed; disarmament and security are not guaranteed; international support is inadequate for economic recovery; civil society, minorities, and women are not included in the peace process. Hence, the new transitional government of Sudan needs to pay careful attention to these issues in order to build a better future.

The editor-in-chief of Sudan Radio Debanga has also rightly pointed out four major challenges of the government: anti-government activities by some political Islamists, marginalized population groups, consequences of the Darfur war, and influences of regional and international powers in shaping the future direction of Sudanese domestic politics. In sum, the future of Sudan lies in at least three areas: the return to civilian-led democratic rule, back to military rule, and the start of a new civil war with the collapse of the Khartoum Power-Sharing Agreement.