Yes, Israel is Committing Genocide in Gaza.

There is no more appalling crime in the realm of international law than the deliberate, systematic effort to erase a people or their culture. As such, the term should be used with care—not only to preserve its moral and legal gravity (though that matters in its own right), but to allow us to assess contemporary conflicts with the clarity they demand.

Which is why I do not say this lightly: the government of Israel is currently committing genocide against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip.

This is not a conclusion I came to hastily. In fact, it is one I reached, with deep reluctance, only a few months ago. But I am far from alone. A growing number of genocide scholars have come to the same determination, among them Brown University’s Omer Bartov, who argued forcefully—and persuasively—for the designation in a recent essay in The New York Times.

It took me time to arrive at the word genocide—and for good reason. The term should never be used lightly, and I’ve long believed that. It’s also because Israel is a country I have lived in, loved, and where many of my friends still live—people I care about deeply. Some will rightly argue that my conclusion came too late. I saw the war crimes as they unfolded, and I’ve written about them in earlier pieces: the staggering civilian death toll, especially among children; the calculated use of starvation; the denial of humanitarian aid wielded as a weapon of war. All of it was impossible to ignore. Even Ehud Olmert, Israel’s former prime minister, has now reached the same conclusion.

When the Israeli Defense Forces began forcibly relocating Gaza’s population from one area to another, and when members of Israel’s cabinet openly expressed their intention to forcibly remove Palestinians from the territory, I conceded that the phrase ethnic cleansing was tragically warranted. But as the death toll mounts and the attacks on civilians waiting for food become ever more brazen, there is no longer a more accurate word to describe what’s happening. The only word that fits—sadly, unmistakably—is genocide.

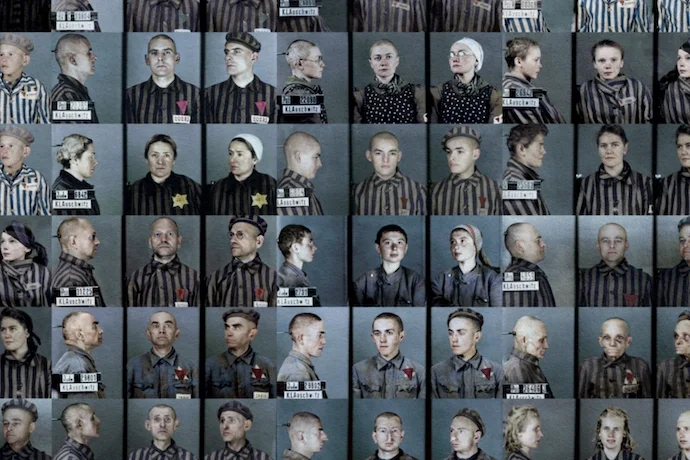

As a student of history and international relations, I find it difficult not to draw certain parallels between today’s events and the world’s most infamous genocide—one that directly preceded the founding of the modern state of Israel: the Holocaust. Just as the term genocide demands careful and deliberate use, so too does any reference to the Holocaust. Comparisons to the Nazis are invoked too casually, too often, and often without due thought to their gravity. I do not make such comparisons lightly. I understand their weight. As someone of Jewish descent, I know how deeply the Holocaust scars the collective memory of the Jewish people. I have walked through Auschwitz and Birkenau and been haunted ever since.

Nor do I believe most Israelis are Nazis. That would be an appalling and inaccurate assertion. But there are extremist settlers and their supporters whose ethno-religious nationalism warrants serious concern—and a disturbing number of Israelis now support forcibly expelling Palestinians from Gaza. My comparison is not between peoples but between governments: their choices, their strategies, and the world’s reaction to them.

We are not witnessing the same scale of atrocity or demographic devastation that defined the Holocaust. That much is clear. But as Professor Omer Bartov emphasized in a thoughtful interview on Fareed Zakaria GPS, genocide does not need to mirror the Holocaust in scope or method to meet the legal or moral threshold. If we move beyond raw numbers and examine structure, rhetoric, and the behavior of the state itself, the parallels between Nazi Germany and present-day Israel become increasingly difficult to ignore.

It begins when a nation channels a legitimate historical grievance into a broader campaign to overturn the existing regional order and cement its dominance. A cynical, egotistical, and authoritarian leader then rises to power, steering the country toward total war with the claim that peace is impossible without the complete destruction of the enemy. To justify this course, the state systematically dehumanizes its adversaries—a defining characteristic of genocide—stripping them of rights and dignity to rationalize the violence. Meanwhile, the international community postures, condemns, and dithers, but ultimately takes no decisive action, enabling the aggressor to continue unchecked. And when the violence finally ends—when the genocide has run its course—those same international actors who once stood by turn to denounce the perpetrators. The offending nation is left to spend generations reckoning with its crimes.

It’s not hard to recognize Hitler and the Nazis in each of these patterns. Seeing the same in Benjamin Netanyahu and the current Israeli government may feel like more of a stretch—but let me walk through each step to make the parallels unmistakably clear.

Germany, reeling from the aftermath of the First World War, harbored a deep sense of grievance and humiliation. The Treaty of Versailles had stripped it of vast swaths of historic territory and imposed punishing constraints on its economy and military. One of the key reasons Hitler was able to rise to power was his ability to tap into this widespread national resentment. He skillfully exploited the German public’s anger at what they saw as an unjust and vindictive peace. And because many global leaders—outside of France—recognized the harshness and imbalance of the treaty’s terms, few were willing to enforce them with any real conviction.

In the aftermath of the horrific attacks of October 7, 2023, Israelis—and much of the international community—were justifiably outraged by the indiscriminate violence and atrocities committed by Hamas. Israel’s desire for retribution was understandable, as was its determination to ensure such attacks would never happen again. But alongside this legitimate response, Netanyahu and his cabinet appeared to see something else: an opening to strike Hezbollah, Syria, and Iran in an attempt to reshape the regional balance of power decisively in Israel’s favor.

Was Israel justified in seeking to protect itself from future Hamas assaults? Absolutely. Did it overreach—deploying force far beyond what could be considered proportional or humane? In my view, and in the view of the International Criminal Court, yes.

Germany, too, harbored valid grievances in the wake of a war it did not bear sole responsibility for starting. But did that resentment justify launching another world war under the banner of Aryan supremacy? Of course not. And that’s the essential caution: the existence of a grievance does not absolve a state of what it does in response.

Having served in World War I and having felt deeply betrayed by the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler sought to correct what he saw as historical humiliations and to restore Germany’s former glory. His scapegoating of Jews—alongside other groups he deemed undesirable—became a convenient and potent political tool. He channeled his personal animus toward Jews, Communists, homosexuals, and others to galvanize supporters around a shared enemy. Those followers, caught up in grievance and fury, failed to recognize the profound flaws, delusions, and dangers embedded in their leader’s vision.

Netanyahu, too, has cynically weaponized the current conflict—though in his case, the motivation is personal survival. Keeping the war going serves his interests. As long as Israel remains in a state of emergency, there is no reckoning for the intelligence and security failures that allowed the October 7th attacks to occur. Nor is there a public reassessment of his leadership, or a political judgment on whether he is fit to remain in office. Most crucially for him, wartime defers the legal consequences of the corruption charges he still faces. As The New York Times Magazine recently reported in detail, Netanyahu has purposefully prolonged the war to avoid political collapse—and prison.

It’s fair to point out that Netanyahu is no raving, ranting lunatic in the mold of Hitler. But he is calculating—coldly so—and he has shown a willingness to do virtually anything to cling to power. That includes sacrificing the broader interests of the Israeli people and the state itself to preserve his own political survival. It also means elevating some of the most extreme figures in Israeli politics—like Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir—by granting them unprecedented influence and unchecked authority.

Once again, uncomfortable parallels with the Nazis and their coterie of appalling figures (Himmler, Goering, and Goebbels, among others) emerge: a governing ethos that rewards brutality, a willingness to embrace ideologues whose views should be relegated to the margins, and a moral calculus rooted in the belief that might makes right. So too does the comparison of targeted populations to animals—textbook dehumanization that has historically preceded atrocities.

Cue the hand-wringing from the international community. Leaders in Britain, France, and Germany express horror at the conditions in Gaza and the unrelenting assaults on Palestinians. And yet, they continue to sell arms to Israel. Joe Biden—a decent man by most measures—has seemed unable to do more than propose withholding some of the United States’ more destructive offensive weaponry. Even that modest effort collapsed under political pressure.

Yes, the International Criminal Court has indicted Netanyahu and charged him with war crimes. That is something. A meaningful first step. But the United Nations Security Council, as ever, remains paralyzed—its ability to act undercut the moment one of the permanent five members has a vested interest. Human rights groups, NGOs, and independent media have documented atrocities with admirable diligence. They have sounded alarms. They have borne witness. But among those with the actual power to halt the violence, little of consequence has been done.

And so, from Netanyahu’s perspective, the logic remains unchanged: no punishment, no deterrence. His calculation holds. “NEVER AGAIN!!!” the international community proclaims—while once again allowing genocide to unfold on its watch.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Germany spent much of the 20th century reckoning with the horrors it had unleashed. Its global reputation as a hub of culture, innovation, and intellectual brilliance was left in ruins. In the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, the world didn’t think of Nietzsche, Goethe, Beethoven, or Kant. It thought of Hitler. And of the gas chambers. Germany became synonymous not with enlightenment, but with genocide.

It took decades of deliberate penitence to begin rebuilding that shattered image—through Holocaust memorials, anti-defamation laws, and the construction of a pluralistic, tolerant democracy. The word “Nazi” remains one of the most potent slurs in modern political language, because Germany’s legacy still carries the weight of what was done.

Israel has yet to reckon with this genocide—because it is still unfolding. But that reckoning will come. Already, its international reputation—particularly among younger generations who never knew a more moral, principled Israel—is in freefall. They don’t think of the vibrant democracy Israel once aspired to be. Or the collectivist ethos that turned desert into farmland. Or the entrepreneurial drive that gave rise to the “Start-Up Nation.” Increasingly, young people draw a different comparison: apartheid-era South Africa.

What comes to mind instead are the now-ubiquitous images saturating TikTok and Instagram: bombed-out neighborhoods, starving infants, grief-stricken families in refugee camps. It’s hard to sweep 55,000 deaths—and counting—and countless amputees, many of them children, under the rug. I lived in post-earthquake Haiti and saw firsthand what a nation of amputees looks like; it’s both haunting and deeply scarring. It scars not just the land, but the soul.

Even if this genocide was executed under Netanyahu’s leadership, it is Israel as a nation—and Israelis as a people—who will bear the burden of its legacy for decades to come. It must be said: many Israelis vehemently oppose this war and Netanyahu’s prosecution of it. Several of my friends have expressed that pain to me, again and again. I feel for them. I speak as an American who has watched my own country launch reckless, devastating wars with disregard for global opinion.

Still, the lesson of history is merciless. Many Germans took no part in the Holocaust. Many were born after it ended. And yet the guilt, the shame, the global judgment endured. This genocide, too, will be a cross for Israelis—present and future—to bear.

My ardent hope is that Netanyahu is removed from power at the nearest possible moment and is held accountable for all of his various crimes, though that seems increasingly unlikely. It’s also my hope that Israel can return to a more moral, more just tradition that befits the Jewish people and the vision under which the country was created: to create a safe space for Jews where they would be free from persecution and genocide. And that Israel can be a part of the resistance to, rather than the reason for, empty cries of “never again.”