Books

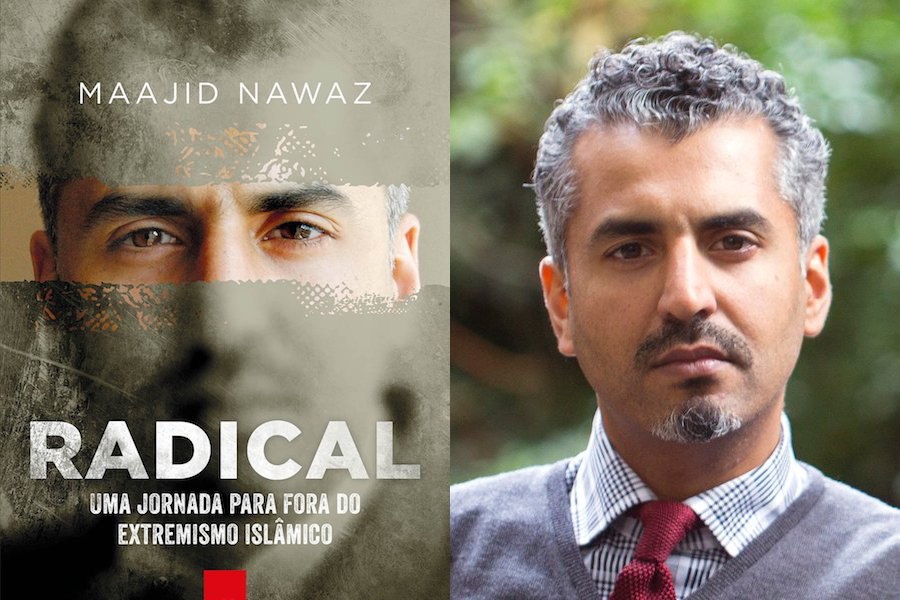

Review of Maajid Nawaz’s ‘Radical’

Maajid Nawaz subtly reveals much in his seemingly effortlessly titled, Radical: My Journey Out of Islamist Extremism. The word radical, though often used in modern English to mean extreme, actually derives its meaning from the Latin word radix, meaning, “root.” Nawaz cleverly employs both meanings—the old and the new—to describe who he once was and who he has now become: a former leader of an Islamist organization who is now on the frontlines of a personal mission to rid Islam of the excessive, politicized ideology he once so firmly believed and forcefully preached.

Nawaz’s Radical, recently released in the United States, is a riveting tale of conversion from a disillusioned British youth to an unremitting Islamist revolutionary. British by birth and Pakistani by descent, Nawaz was an unwary young boy who, during his adolescence, struggled to assimilate into the predominately Anglo seaside town of Southend. “A moving target,” he bore the burnt of discrimination and harassment at the hands of his classmates, and later and more intimidating, from ultranationalist skinheads.

Lost and disgruntled, Nawaz found some solace in the revengeful lyrics and anti-establishment strain of 90s American hip-hop music.

Professor Griff, an Islamic zealot and member of the infamous rap group Public Enemy, made a particular impression on the young, credulous Nawaz. His faith was now nothing to be ashamed of, but had now been “re-branded as a form of resistance, as a self-affirming defiant identity.”

Nawaz’s background made him particularly susceptible to what he calls the narrative. The narrative gave Nawaz a compelling, alternative explanation for his tribulations: the suffering and attacks he experienced were not isolated incidents, but part of a larger Western affront to destroy Islam. Under the skillful persuasion of a recruiter, Nawaz becomes a member of the extremist group Hizb ut-Tahrir. What follows is a sprawling meander through Nawaz’s rise from a novice to a lead recruiter and his stints in Pakistan, Denmark, Palestine, and Egypt. He is careful to salt the gripping narrative with penetrating insights into the inner workings and tactics of a reputable Islamist organization.

The most captivating section of the book comes toward the end as Nawaz vividly recounts his time in a dreaded torture chamber in Mubarak’s Egypt for promoting his group in the autocratic country. His account is as enthralling as it is haunting. For instance, the scene in which Nawaz nervously awaits to be called for interrogation while the deafening cries of those called before him linger in the background is told with such excruciating detail that the reader is left arrested in suspense, anxiously awaiting for what comes next.

Radical is ultimately a redemptive tale, and it is in prison that Nawaz, at long last, is set free from the ideology that has held him captive. His close readings of Islamic text and its varied interpretations (to which he had astonishingly not yet been introduced) and long conversations with reformed, convicted former terrorists led Nawaz to conclude that Islamism was a mere “political ideology dressed up a Islam.”

Islamist extremism and how best to confront it has become a remarkably divisive issue in both America and England, and both political classes come away moderately scathed in Nawaz’s book. He offers in passing a revealing critique against the left whose passionate resistance against western aggression, he argues, often blinds them to the deceitful ways of Islamists and the severity of their threat to the West. Groups such as Amnesty International are amicably criticized for conflating the differences between victims of human rights abuses and champions of human rights causes. For Nawaz, the two are not necessarily the same. The right is also duly criticized. He faults them for not fully acknowledging the tremendous effect grievances have in fermenting extremism.

While Nawaz offers some useful criticisms, he does remarkably little to sufficiently articulate a comprehensive remedy to the problem he so elegantly describes. He argues that a counternarrative—a narrative that emphasizes values such as human rights, pluralism, and democracy—is needed in the Muslim world to change the hearts and minds of the masses. His answer, though, is ultimately vague and lackluster. For example, he writes the counternarrative needs to permeate all segments of society and have the backing of different coalitions, but he fails to adequately explain how such a vision can become reality. Moreover, his unfailing reliance on democracy to curb Islamism is more complicated than Nawaz makes it appear. History, and the most recent events in Egypt, reveals that democracy and moderation in the Muslim world do not necessarily go hand in hand.

In addition, for an edition written for an American audience, Radical is curiously absent of any serious discussion of U.S. policy and whether it is ultimately curbing or abetting the promotion of Islamism. The reader is left anxiously awaiting Nawaz’s views on the effect of drone attacks and the recent Arab Spring only to be let down in the end. Nawaz would have been wiser to focus on these issues in the last few chapters of the book rather than writing in a transparently promotional tone about his counter-extremism think tank, Qulliam.

Writing about policy ultimately runs the risk of alienating potential readers, and perhaps Nawaz did not want that to stand in the way of people being receptive to his story. Nevertheless, in the end, Radical is a mesmerizing tale of personal struggle and inner growth that should be diligently read, not only by policymakers in Washington, but by anyone interested in global phenomena of religious and political extremism.

“Ideas are like water” Nawaz writes, “they take a while to reach a boiling point, but as soon as they do, they erupt.” One can only hope that Nawaz’s truly radical idea of moderation will reach a boiling point sooner, rather than later.