All ‘Fury,’ No Fanfare

For Fury (2014), a film that breaks some of the conventions of the World War II genre, composer Steven Price delivers a score that breaks musical conventions. No fanfares. No romance. No marches even. Only horror upon fiery horror.

Consider Fury’s genre antecedents.

In the years following World War II, Hollywood produced a swath of films remembering the war’s glory, heroism, and romance. Musically, the genre kept to three staples: the march, the victory fanfare, and the romantic interlude.

British film composer Ron Goodwin was exemplary of this trend. He composed war eagle portraitures for films like Battle of Britain (1969), 633 Squadron (1964), Operation Crossbow (1965), and Where Eagles Dare (1968).

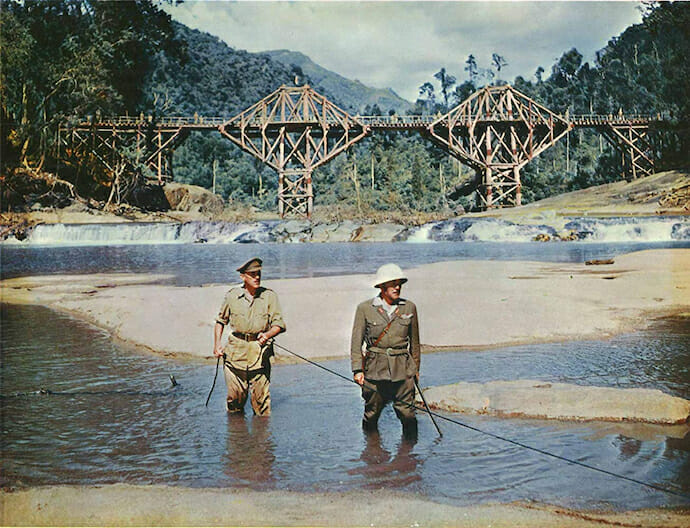

Even The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), a profound antiwar statement, mostly honored the musical formula.

King Rat (1965), composed by John Barry, was an important exception. The march in the score is sardonic and cacophonous, fitting for a POW protagonist who cooks up rats for unsuspecting officers. Instead of pompous, the march is meager and tinny. The “daily life” theme features oboe and cimbalom as voices of despair.

Only in the 1970s did film music of World War II begin to change industrywide, paralleling changes in the depiction of war onscreen. The music began to reflect the psychology of warriors and the tragedy of mass destruction.

Composer Jerry Goldsmith was pivotal in this new direction. Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora!, both released in 1970, convey some of Goldsmith’s finest, darkest work.

The main title to Patton is a union of three aspects of the general’s biography: piety, pride, and the salience of antiquity and reincarnation. Somehow, Goldsmith manages harmony between these components. The main title to Tora! Tora! Tora! uses Japanese instruments to build a haunting melody. Musical tension escalates as the Japanese war machine targets Pearl Harbor.

The 1990s saw major reform in World War II genre scoring technique, as films lost their moorings on hope and glory. Grittier commentaries on World War II included Schindler’s List (1993), The Thin Red Line (1998), Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), and Saving Private Ryan (1998).

(Columbia Pictures)

One of the famous cues in Hans Zimmer’s The Thin Red Line, “Journey to the Line,” narrates American troop movements toward battle in Guadalcanal. This arena, typically saturated with brass, is instead scored mostly with strings and light percussion. The brass that do speak are subdued, befitting a dirge.

Fury joins this rich musical tradition with an original contribution by composer Steven Price. Price won a Best Original Score Oscar last year for Gravity. In a recent interview, he describes his general approach to Fury: “There have been so many amazing World War II scores over the years, but I think he [Director David Ayer] felt and I did, that it’s been done so well that we have to find something distinctive to the way we’re telling the story. So he was very open to me to experiment and try things and that’s what I did.”

The score addresses three aspects of the plot: first, the fanaticism of Nazi Germany in its last throes; second, the claustrophobic, bloody, loud life of a tank soldier; and third, to a lesser extent, elegy to the fallen.

The first cue on album, “April 1945,” exemplifies the instrumental themes of the film: a baritone German choir voices the Nazi opposition; synthesizer and percussion voice the tank machinery; and the strings section and a solo female singer voice the sorrow of war.

Composer Steven Price explains developing the eerie German choir sound: “It was never designed to be heard, but it’s just always there – this Germanic presence that is almost taunting them. Many times the words are entirely inaudible. To achieve that, I would give different passages to the choir. So, one half would sing something and the other half would sing something entirely different. It really made it feel like the sounds are coming from all around you and I have to say it got very eerie when we were recording it. The first time I did it I wasn’t sure it was going to work, but in the sessions we got them to whisper and everyone in the control room just shrunk in their chairs. We all looked at each other and went, ‘oh, that’s quite spooky!’”

The rest of the score varies little from “April, 1945.” Clearly, the composer aims for atmosphere and rhythm to be the dominant elements of his soundscape.

The final cue, “Norman,” speaks with notable melodic force absent in the rest of the score. The harsh tenor of the strings section is reminiscent of film composer Dario Marianelli’s work in Atonement (2007).

Price’s score deserves acclaim for rising above the thundering sound of tank fire in Fury. It deserves recognition for capturing the heavy rhythms of mechanized warfare.

Without martial trumpets, without snare drums, warfare never seemed so wretched. That is the score’s highest achievement.