A Very Brazilian Coup

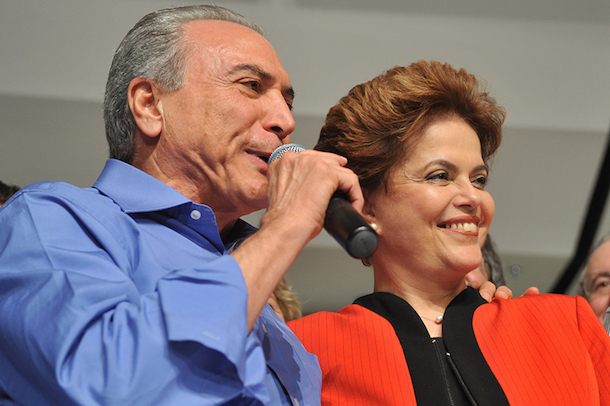

On one level, the impeachment of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff seems like vintage commedia dell’arte: the Lower House speaker who brought the charges, Eduardo Cunha, had to step down because he has $16 million stashed in secret Swiss and U.S. bank accounts. The man who replaced Cunha, Waldir Maranhao, is implicated in corruption around the huge state-owned oil company, Petroblas. The former vice-president and now president, Michel Temer, has been convicted of election fraud, and has also been caught up in the Petroblas investigation. And the president of the Senate, Renan Calheiros, has also been implicated in the oil company scandal and is dodging tax evasion charges. In fact, over half the legislature is currently under investigation for corruption of some kind.

But there is nothing comedic about what the fall of Rousseff and her Workers Party will mean for the 35 million Brazilians who have been lifted out of poverty over the past decade, and for the 40 million newly minted members of the middle class one-fifth of Brazil’s 200 million people.

While it was the current downturn in the world’s seventh largest economy that helped light the impeachment fuse, the crisis is rooted in the nature of Brazil’s elites, its deeply flawed political institutions, and the not so dead hand of its 1964-1985 military dictatorship.

Given that the charges against Rousseff do not involve personal corruption, or even constitute a crime—if juggling books before an election were illegal, virtually every politician on the planet would end up in the docket—it is hard to see the impeachment as anything other than a political coup. Even the conservative Economist, long a critic of Rousseff, writes “in the absence of proof of criminality, impeachment is unwarranted” and “looks like a pretext for ousting an unpopular president.”

That suspicion is reinforced by the actions of the new President. Temer represents the center-right Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) that until recently was in alliance with Rousseff’s Workers Party. As soon as Rousseff was impeached by the Senate and suspended from office for 180 days, Temer made a sharp turn to the right on the economy, appointing a cabinet of ministers straight out of Brazils’ dark years of dictatorship: all white, all male, and with the key portfolios in the hands of Brazil’s historic elites. This is in a country where just short of 51 percent of Brazilians describe themselves as black or mixed.

Seven of those ministers have been implicated in the Petroblas scandal.

The President announced a program to “reform” labor laws and pensions, code words for anti-union legislation and pension cuts. His new Finance Minister, Henrique Meirelles, a former central bank head who once headed BankBoston in the U.S., announced that, while programs for the poor “which don’t cost the budget that much” would be maintained—like the highly popular and successful Bolsa Familia that raised tens of millions out of poverty through small cash grants— other Worker Party initiatives would go under the knife.

The new government is already pushing legislation that would roll back laws protecting the environment and indigenous people, and has appointed ministers with terrible track records in both areas.

One of the largest soybean farmers in Brazil, Blairo Maggi, was appointed Agriculture minister. Maggi has overseen the destruction of vast areas of the Amazon to make way for soybean crops. Temer’s initial appointment for Science minister was an evangelical Protestant minister who doesn’t believe in evolution. Temer also folded the culture ministry into the ministry of education, sparking sit-ins and demonstrations by artists, filmmakers and musicians.

Brazil has long been a country with sharp divisions between wealth and poverty, and its elites have a history of using violence and intimidation. Brazil’s northeast is dominated by oligarchs who backed the 1964 military coup and manipulated the post-dictatorship constitution.

Political power is heavily weighted toward rural areas dominated by powerful agricultural interests. The three poorest regions of the country, accounting for only two fifths of the population, control three quarters of the seats in the Senate.

As historian Perry Anderson puts it, the political system was designed “to neutralize the possibility that democracy might lead to the formation of any popular will that could threaten the enormities of Brazilian inequality.”

Brazil’s legislature is splintered into 35 different parties, many of them without a political philosophy. The legislature is elected on the basis of proportional representation, but with an added twist: an “open list” system in which voters can choose any candidate, many of them standing on the same ticket. The key to winning elections in Brazil, then, is name recognition, and the key to that is lots and lots of money. Most of that money comes from Brazil’s elites and the oligarchs in the country’s northeast.

Because of the plethora of parties, forming a government is tricky. What normally happens is that one of the larger parties ropes in several smaller parties by giving them ministries. Not only does this encourage corruption—each party knows it needs to raise lots of money for elections—but results in political incoherence.

When the Workers Party was elected in 2002 it was unwilling to dilute its programs by bringing ideological opponents into a cabinet, yet the Workers Party needed partners. The solution was cash payouts to legislators, a scheme titled “mensalao” (“monthly payoffs”) that was uncovered in 2005. Once the payoffs were revealed, the Workers party had little choice but to fall back on the old system of handing out ministries in exchange for votes. That is how Temer and the PMBD entered the scene.

With the reputation of Silva and the Workers Party dented by the payoff scheme, the right saw an opportunity to rid themselves of the left, but Silva’s popularity and the success of programs aimed at alleviating poverty made the Workers Party pretty much unassailable at the ballot box. Silva won another landslide election in 2006, and Rousseff was elected twice in 2010 and 2014. In short, the elites could not win elections.

But they could still pull off a very Brazilian coup. First, they hammered at the fact that some Workers Party leaders had been involved in corruption and others implicated in the Petroblas bribery scheme. Rousseff headed up Petroblas before being elected President. While she has never been linked to any of the corruption, it did happen on her watch.

Petroblas is rated the fourth largest company in the world, and it is building tankers, off shore platforms and refineries. That expansion has opened opportunities for graft, and the level of bribery involved could exceed $3 billion. Nine construction companies are implicated in the scandal, as well as more than 50 politicians, legislators and state governors, including the PMDB and the Workers Party.

Rousseff’s biggest mistake was to run on an anti-austerity platform in 2014 and then reversing course after she was elected, putting the brakes on spending. The economy was already troubled and austerity made it worse. The 2005 bribery scheme lost the Workers Party some of the middle class, and the 2014 austerity alienated some of the Party’s working class support.

But it was most likely Rousseff’s decision to green light the Petroblas corruption investigation that spurred her enemies to strike before the probe pulls down scores of political leaders and wealthy construction owners. One of Temer’s ministers was recently caught on tape plotting how to use the impeachment to derail the investigation.

Certainly the campaign aimed at Rousseff was well orchestrated. Brazil’s media—dominated by a few elite families—led the charge. According to Reporters Without Borders, the role of the media was “partisan,” its anti-Rousseff agenda “barely veiled.” Judge Sergio Moro, who is a key figure in the Petroblas investigation, illegally leaked wiretap intercepts that put Silva and Rousseff in a bad light.

Given the makeup of the Brazilian Senate, it is likely Rousseff will be convicted and removed as President. It also appears that Temer will try to roll back many of the programs that successfully narrowed the gap between rich and poor.

Brazil’s economy is in trouble, shrinking 3.7 percent last year. Commodity prices are down worldwide, in large part because of the downturn of China’s economy. Iron ore dropped from $155 to $55 a ton, soya went from $18 to $8 a bushel, and oil from $140 to less than $40 a barrel.

Brazilian debt is rising, but it is still half that of Italy, and unemployment is low, at least by European standards. A return to the austerity policies that destroyed economies all across the southern cone during the 1980s and ‘90s would be a disaster. The worst thing one can do in a recession is curb spending, which stalls out economies and puts countries into a debt spiral.

The austerity policies of the European Union have kept all but a few European economies virtually dead in the water, and those that have shown some growth, like Spain, still post unacceptable unemployment rates. Spain currently has an overall national jobless rate of 21 percent, rising to almost 50 percent among youth. Brazil’s jobless rate is 10.9 percent.

For now, the Workers Party is on the ropes but hardly down and out. It has 500,000 members, and the new government will find it is very difficult to take things away from people now that they have gotten used to having them. Some 35 million people are unlikely to return to their previous poverty without a fight.

One of Temer’s first acts was putting up 100,000 billboards all over the country with the slogan: “Don’t speak of crisis; work!” which sounds a lot like “shut up.” Brazilians are not noted for being quiet, particularly if the government instituting painful cuts is unelected.

The pressure for new elections is sure to grow, although the current government will do anything it can to avoid them. Sooner or later there will be a reckoning.