A Year On from the Coup that ‘Changed the Face of Kazakhstan’

Just over a year on from Kazakhstan’s ‘Bloody January,’ much appears to have changed in Kazakh politics. The government, in power since March 2019, has engaged in an apparently comprehensive reform programme that has liberalised elements of Kazakh political culture, with the goal of transitioning Kazakhstan to a legitimate parliamentary system. Combined with the exclusion of former President Nursultan Nazarbayev from the political system, and the government’s public opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Western observers have increasingly identified an impending shift in Kazakhstan’s strategic orientation and political culture.

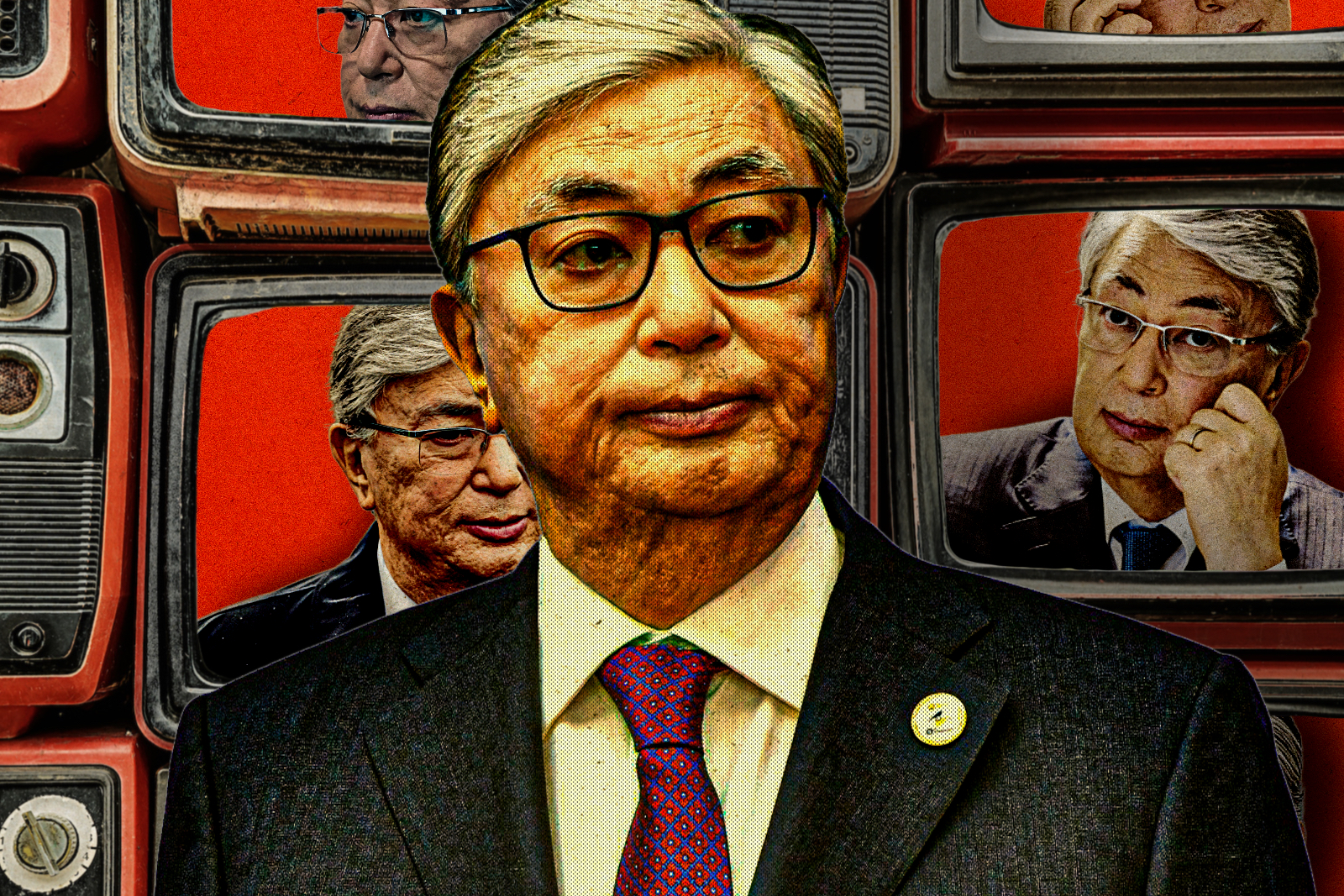

In reality, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is simply running the Putin Playbook, a campaign of cosmetic reforms, catalysed by a national crisis, to ensure his hold on power absent substantive strategic and political changes. The West should avoid this trap and resist attempts to cannibalise the Kazakh state for personal gain. In this game of country-versus-president, once again the strongman and his clique seek to press an advantage.

The current government nominally took power in March 2019, following Nursultan Nazarbayev’s resignation in the midst of nationwide protests. Over a decade younger than Nazarbayev – and therefore nominally from a “new generation” of political leadership – Tokayev assumed the presidency at 65. A long-term fixture of the political system, he was nevertheless not a political functionary with an independent power base, but rather a Soviet-trained professional diplomat who briefly served as prime minister, then as foreign minister, and as the Director-General of the UN’s Geneva Office, before returning to the Kazakh Senate.

Tokayev’s selection as Nazarbayev’s successor likely stemmed from his largely technical-diplomatic career. A sort of elder statesman with extensive diplomatic contacts, he could serve as the face of a political system that could not create a viable political economy.

The current government waited nearly three years to make a more aggressive move and nationwide protests in 2022 offered an ideal opportunity. Until official government records are made available, we will never truly know the root causes of the unrest. But once Russian troops arrived, under the guise of “peacekeepers,” Tokayev’s government moved quickly.

Since then, the government has solidified power through a snap presidential election and passed constitutional reforms that would advantage the ruling Amanat party. All the while, the government has protested the Russian invasion of Ukraine and repeatedly denied that Kazakhstan has helped Russia evade sanctions.

To the external observer, Tokayev’s government has played the part of incremental reformers, dispassionate technocrats capable of getting along well with Western powers, and – dare we hope – people with some commitment to international law. After all, they have vocally refused to recognize Donetsk and Luhansk, the two Russian-supported pseudo-states in eastern Ukraine, and have repeatedly dissented against Vladimir Putin’s bloody crusade to clense Ukraine of its identity.

The reality, however, is far more troubling. Tokayev has consolidated power much like Putin did in the early 2000s. Similar to the Russian securocrat-in-chief, Tokayev became a relatively nondescript if competent functionary who, Nazarbayev likely believed, would pose no threat to the status quo. Much like Putin early on in his tenure, Tokayev has promised various liberalizing reforms and engaged with the West. And like Putin, Tokayev has used a major political crisis to sideline and defeat his rivals, including Nazarbayev. This week’s OSCE Winter Meeting in Vienna was a clear indication of the government’s true affiliations, where out of the 52 countries present only Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan did not stand up during a moment of silence observed for the victims of the war in Ukraine.

Three pieces of evidence demonstrate the government’s current faux-liberalization as fraudulent.

First, despite its commitment to combat corruption and return stolen wealth to the people, those who have been most clearly responsible for building the kleptocracy that Kazakhstan is today, remain untouched. These include oligarchs Timur Kulibayev, the son-in-law of Nursultan Nazarbayev, accused in the Financial Times of masterminding a “secret scheme to skim millions off central Asia’s pipeline megaproject.” Also untouched is Bulat Utemuratov, identified by British parliamentarians as Nazarbayev’s personal money manager and, by some estimates, worth over $4 billion. Nazarbayev’s family similarly remains untouched financially, with Dariga Nazarbayeva still owning a significant number of properties in London. Conveniently glossing over certain individuals, despite a commitment to clean up corruption, seems to be standard practice, with the only thing changing being the kleptocrat in charge to who the oligarchs report.

Second, things haven’t really improved for Kazakhs, despite nominal commitments to political liberalization. The government has made support for human rights, along with education central to its image. Nevertheless, the government still detains citizens without trial, imprisons activists, harasses now-legal trade unions, and turns a blind eye to torture. Government cronies, such as Aslan Sarinzhipov, the former Minister of Education, have been singlehandedly responsible for destroying the education system, which deteriorated significantly during his tenure due to high-profile allegations of exam results fraud.

Most critically, Kazakhstan has remained a crucial conduit for Russian sanctions evasion despite public opposition to the Ukraine war. Kazakhstan’s trade with Russia has actually increased significantly since Putin invaded Ukraine. Kazakhstan has become a crucial transshipment point for all manner of goods, including Chinese consumer electronics and automobiles. For all of Kazakhstan’s bluster and claims of opposing the war in Ukraine, the country remains a key partner for Russia economically.

The West must not fall for the Putin Playbook once again. The grey-hared, genteel Tokayev and his allies are not people with whom business can be done. Pressure is needed – pressure against the campaign to destroy private Kazakh wealth and to disrupt his government’s obvious links with China and Russia – to achieve any progress in the long term.