Culture

Artists Mustn’t Sully the Principle of Human Rights

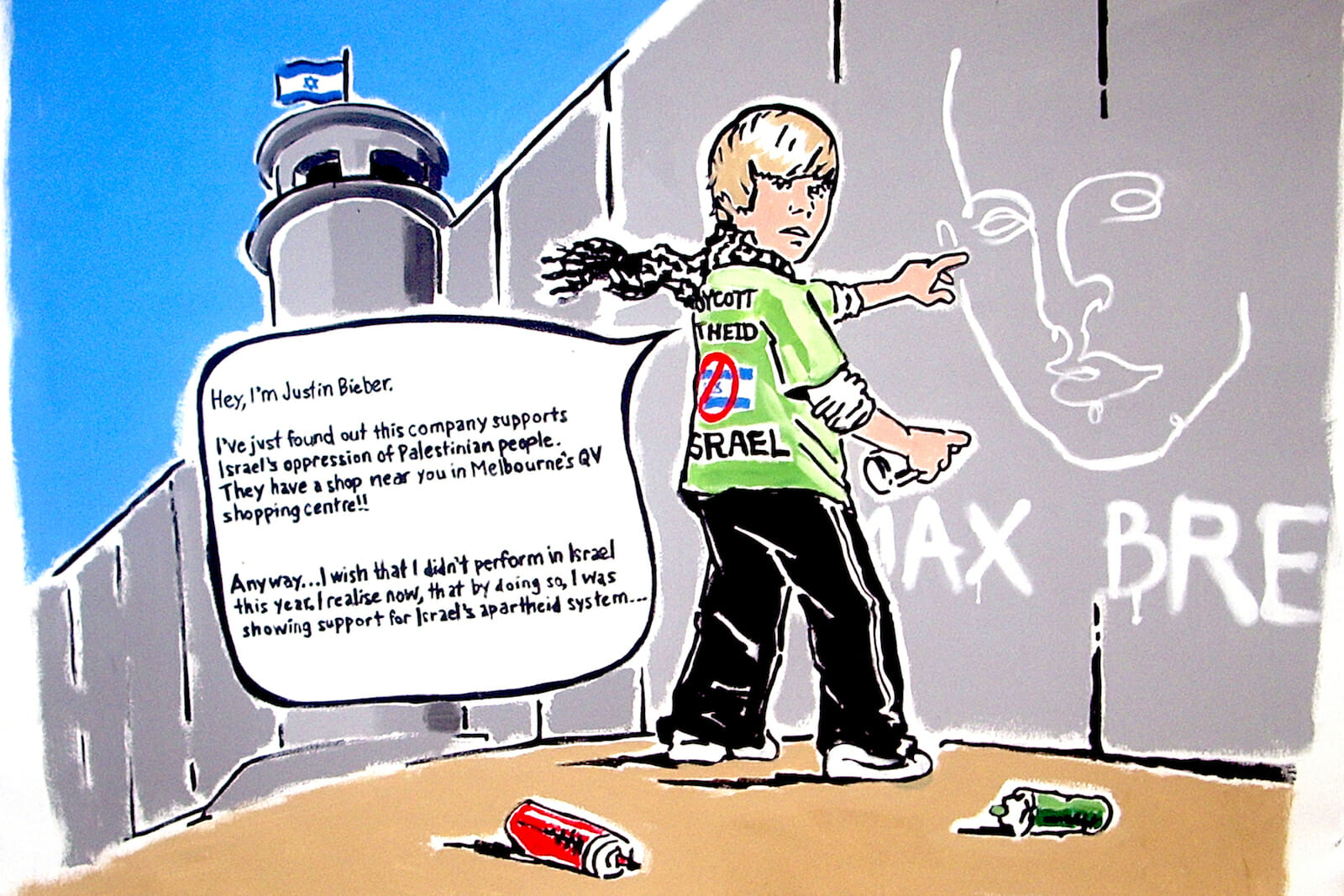

Van Rudd’s work Pop Goes the System was absent from the opening Human Rights Arts and Film Festival in Melbourne. The piece consists of two cartoons, printed front and back on a large canvass. On one side Justin Bieber — a Canadian teen pop idol who recently toured Israel — is depicted spray-painting the separation barrier in the West Bank alongside various messages in support of the boycott of Israeli products and services. On the other side, in an apparent tribute to the Arab Spring, an exploding suicide bomber is juxtaposed by a message about the uprisings’ effective use of “people power.”

Rudd, who is the nephew of the Foreign Minister, issued a strongly worded statement on his personal website in which he suggests he was censored by festival organisers for inciting “racism,” “violence” and “division.” Festival organisers have responded to Rudd’s claims by stating that the piece “doesn’t fit the theme of the show.” Furthermore, since it was received two days prior to the opening and thus did not meet the terms of his commission.

And yet it is Rudd’s claim that the omission of the work from the festival “infringes on the individual human right of freedom of expression through art” that is most troubling. Regardless of the validity of Rudd’s claims, his response sullies the principle of human rights as it is often used in democratic and developed states like Australia — to the detriment of those who may purposefully need to call on it, including the Palestinian people whom Rudd purports to defend.

The right to artistic expression does not require that all works, at all times, must be accepted for viewing in all places. The artist must acknowledge that their individual rights must balance and complement other competing rights. On a more practical level, there must be a mechanism for not invoking this principle over what is subjectively deemed “bad” art.

To expect support from patrons of the festival, Rudd might have afforded them the same level of space that he demands for his art. Instead his actions prompted his supporters to picket the entrance of the festival and distribute his statement, voice their opinions on the state of Israel and various aspects of the historical Middle East conflicts, advocate for the pro-Palestinian BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) Campaign, as well as continually film patrons — including me — entering, exiting and inside the gallery.

In the proceeding days, Rudd’s statement has been distributed across national and international news media outlets. Having recently helped facilitate a formal dialogue between the Israeli-Jewish and Palestinian-Arab diaspora in Melbourne, I know there are a number of reasoned and progressive leaders who support the boycott of Israel. However, they generally acknowledge that such a position seeks to isolate Israel, economically and diplomatically, and leaves little room for dialogue.

Instead, the pro-Palestine boycott logic rests on the belief that any harm incurred by Israelis will be outweighed by the gains in human rights for Palestinians. In the same way, to activate a boundary between those that boycotted the festival (“us”) and those that chose to attend (‘they’) was intentionally divisive. If the target of the pro-Palestine BDS Campaign is Israeli products and services, then it seems a stretch to include activities like Rudd’s under its rubric.

Unless Rudd was invited to do so, it is arrogance indeed to elevate the importance of his work to the level of an international human rights campaign. More controversially, I believe that Rudd’s work is not just simply a piece of art, it is visual activism. It should not therefore be unquestionably afforded the full range of artistic freedoms he demands. To be sure, the statement that accompanied Rudd’s work was laden with emotive language and a cherry-picked selection of historical accounts of the Israel-Palestine conflict. The artwork itself forcefully puts forward a number of arguments so as to make its message plain and clear, yet exclusionary and divisive.

All up, Rudd conveyed less about Palestinian human rights than one particular political response to Palestinian human rights. I myself am by no means afraid or immune from forcefully expressing my political views on Israel, but they are published as opinion pieces, not behind the veil of literature. In the past I have suffered thanks to reactions to my published work. Thus I make no claims for denying Rudd his artistic freedom.

What I object to is Rudd’s claim to freedom of expression based on some objective reality. Any representation of the ‘facts’ of world politics is necessarily altered by the way in which they are presented. This applies as much to the scholar as it does the artist. A useful illustration of this dilemma is neatly captured in the practice of war photography. Commissioned by the British to document the “reality” of the Crimean War, one of Robert Fenton’s most lasting images is that of spent cannonballs, strewn along a road.

Yet in fact, as art historian Ulrich Keller argued nearly 150 years later in The Ultimate Spectacle: A Visual History of the Crimean War, the photograph entitled The Valley of the Shadow of Death was staged; Fenton is known to have taken a second shot of precisely the same scene, albeit with piles of cannonballs clustered by the roadside, and the road cleared. As Keller argues, the cannonballs were either carefully placed on the road to give an immediacy to Fenton’s image that it would otherwise have lacked, or Fenton took a second exposure after the cannonballs were removed so that his cart could continue on just behind the battle.

Fenton’s image is useful, therefore, not as evidence of what really happened during the Crimean War, but as an aesthetic object, and as a document of how one photographer chose to represent it.

It is how the gap between reality and representation is treated that gives artworks the potential to enhance our understanding of world politics. Most scholars of international relations pursue a mimetic representation of reality by employing the methods and interests of the sciences whereas aesthetic politics brings a reflective understanding to its many conflicts and dilemmas by presenting itself as a form of representation.

Van Rudd’s work and statements tend more towards the former than the latter — they offer little in the way of reflective understanding, and instead demand validity based on the “facts” of world politics. Artists must use such “facts” cautiously. To put it more crudely: visual activism must have enough value as art to cover any political liability; otherwise it’s just bad politics.