Politics

Breaking the Addiction to Hate Language

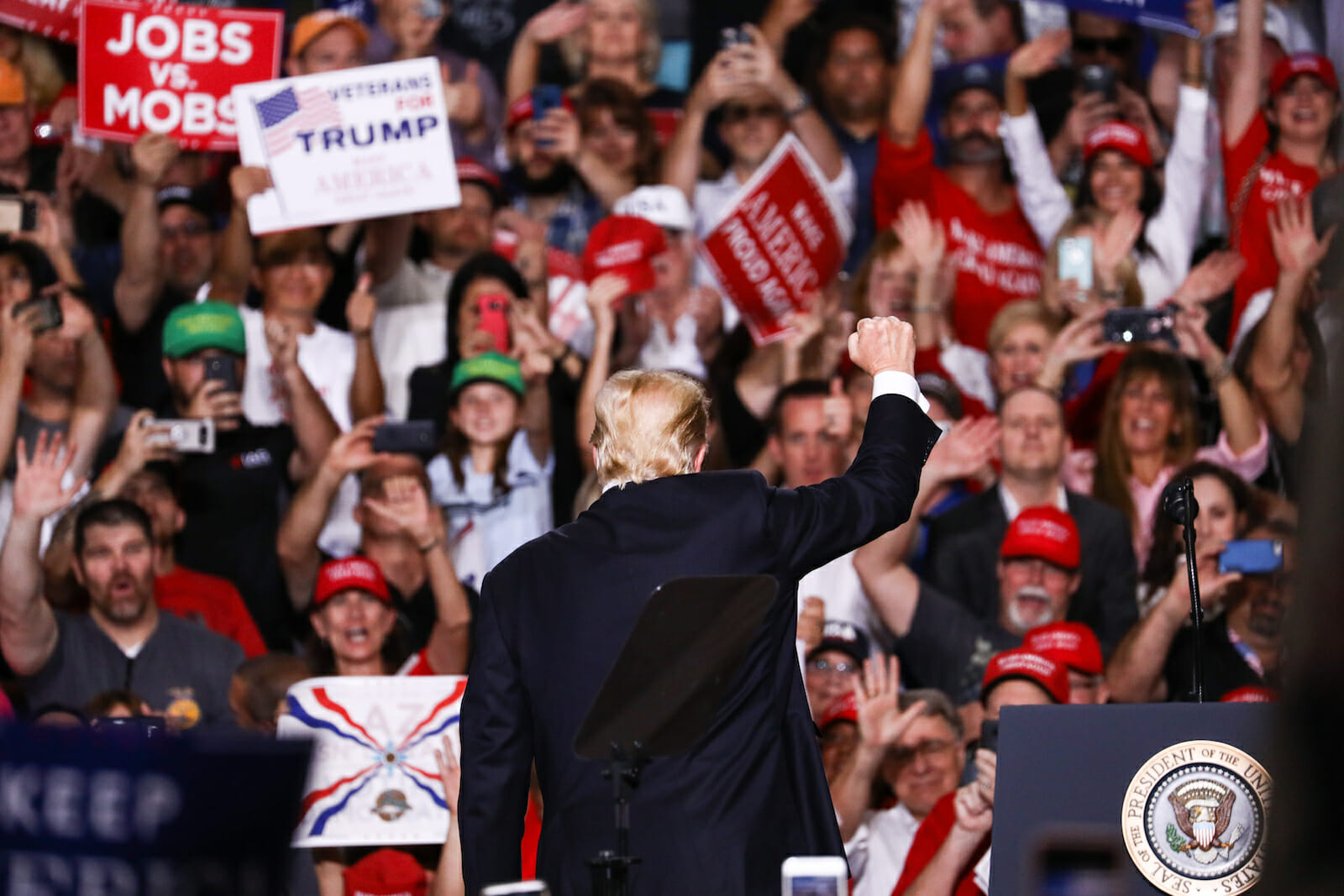

The news cycle starts with it every morning. “The president was busy overnight…” then goes on to quote the president’s latest tweet. Whether he is vilifying Rep. Elijah Cummings or the four congresswomen of color who make up “The Squad.” His first tweet of the day is the gateway drug to the addiction that follows.

Trump’s words are discussed on all news outlets, the extensive morning shows, the all-day coverages, the signature news shows from “Rachel Maddow” to “Fox & Friends,” all referring to the tweets and their incendiary nature. He is retweeted, with and without commentary, and those tweets are also retweeted and give a handful of words powerful exposure. Finally, the night-time variety and news shows use the tweets in the riffs by Stephen Colbert, Seth Meyers, Trevor Noah, and others, as evidence of impropriety, or incompetence relieving our tension. It would be funny if it wasn’t so sad.

I’ve had people say to me (and to others), “have you seen his latest? Can you believe what he said?” Among like-minded people, there is not much critical analysis, because the words don’t have much nuance. By the end of the day, we are satisfied with our reaction, our repeating, our modifying it in our own psyche; we are ready to move on to dog-rescue videos and wait for the next day and the next tweet.

I’ve tried to stop my own participation, but the presence, the unceasing conversations, the deep need to share the needle, persists. I’ve been on a Facebook break for a few months, but when a tragedy like the El Paso Walmart massacre happened, I rushed to Twitter to join my online community’s outrage, to use their words and statistics to support my own views. I retweeted the U.S. statistics on mass-shootings; I examined the pictures of people in grief. I got mad and retweeted. That’s it. Coffee’s ready.

In an article by Ezra Klein on Vox.com, he questions the selective-media coverage of Trump: “The effort to avoid normalizing Trump has been operationalized by, in effect, lowering the bar to covering Trump. We’re on high alert for his abnormal statements — moments of racism, sexism, or bigotry; outright lies; flirtations with fascist ideas or autocratic leaders — so all he needs to do to refocus the political media and thus the country on the worst possible conversation is to make a comment that falls into one of these buckets.”

Klein notices too, we are thriving on his hate, and while we may cringe in disapproval; for many people, like the mass-shooter Patrick Crusius in El Paso, it is also inspiration. It cuts both ways.

Language matters and given enough messaging, we can be convinced to shift our usages, our verbiage, and perceptions. Mass shooters themselves have verified this malleability. Evidence is present Crusius had a manifesto that expressed his alignment with the mass shooter in New Zealand. Both admired Trump and his demonizing of immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees, and other races and religions. Santino William Legan, the shooter at the Gilroy Garlic Festival just a few days ago, posted messages designating his ideologies. The social media accounts and literature found in the shooters’ residences confirmed a loyalty to Trump and in addition, extremist tendencies proffered by white nationalist propaganda.

Many argue that Trump cannot be blamed, because while his messaging may be repulsive, he hasn’t directed these murders.

His participation and his flamboyance are key to how these events unfolded. In 1951, Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements analyzed the movements that shifted global history, such as Nazism in Germany or Stalinism in Russia. Every movement starts with the writer/the intellectual who creates the idea, generates the dogma that feeds the movement. These precepts are delivered by the fanatic. The fanatic develops both the emotional appeal, as well as, framing the movement as the only hope. They capture the attention of the frustrated population, ready to become believers. The fanatic’s charisma stems from their seemingly independent nature—not tied to the old establishment.

The final phase of the movement, the really scary one, that is referred to in Ezra Klein’s article, is the bureaucratization or the normalization of the movement. We know this is developing because of the addiction to the screens that deliver the message. We aren’t Germans in the streets listening to speeches over scratchy loudspeakers anymore. Our phones bring the message to our ears, minds, and hands. We sacrifice nothing to receive these messages.

According to Hoffer, the seeding of the movement can be tiny: “It is remarkable how much a pinch of malice enhances the penetrating power of an idea or an opinion. Our ears, it seems, are wonderfully attuned to sneers and evil reports about our fellow men.”

Our addiction to the sneers and evil reports pushes the movement even further into the middle. The bureaucratization is fast-tracked because our tools are more efficient and available. We are in anticipation of the next message, the new perspective, and the communal reactions. But the fact is, we are not going to give up social media or stop reporting the tweets of the president.

The tracks of this dependency are lacing our arms and the train is moving fast. Perhaps we should treat this addiction like others. We need intervention and a groundswell of activity: from the media outweighing the stories of extremism to examining our own participation in this cycle. Rather than repeating the language or hitting the “like” icon, we should deepen the conversation. We need to detach from the language of others and free our own expression to the core of our beliefs. A multiplicity and complexity of views complicate the tendency to “sign on.” When the messages are personal, individual, creative and smart, they counterbalance the robot-like responses we are experiencing. We can have hope: If one man can influence with a “pinch of malice,” a competing chorus can certainly do the same.