Challenges Remain for China as Party Marks Anniversary

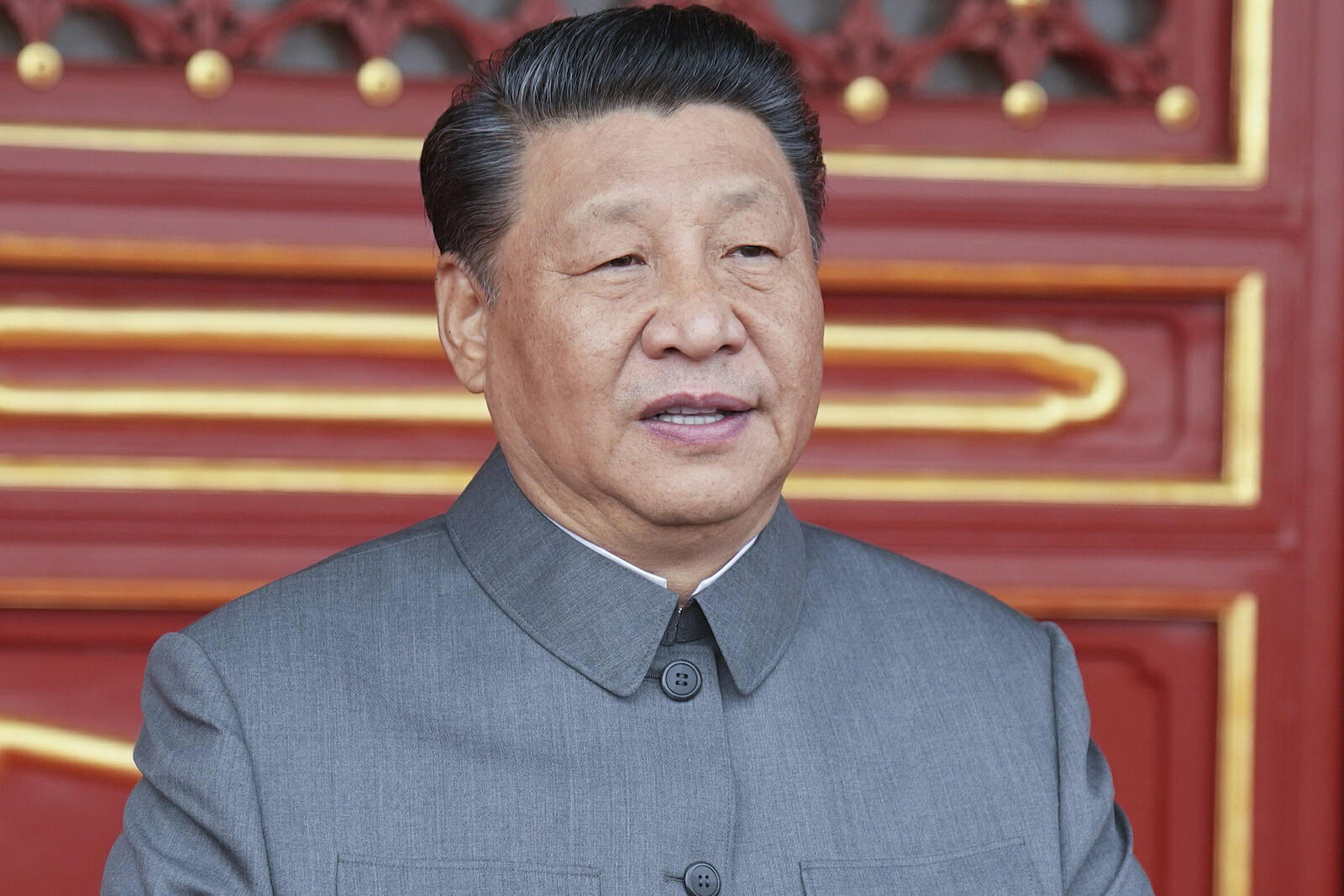

BEIJING, China – Even the weather seemed to be obeying the script. At 9 am on Thursday morning a brief thunderstorm hit northern Beijing. Nothing unusual in that, it is after all the height of summer and the rainy season. But about 20 kilometres away in central Tiananmen Square where President Xi Jinping was leading celebrations to mark the Chinese Communist Party’s 100th anniversary, the massed ranks remained largely dry. The storm passed. Nothing, it seemed, would get in the way of the Party’s party.

Napoleon may not have actually said it but the quote attributed to him has taken on a prophetic air. China has awakened, it has shaken the world but perhaps not in the way envisaged by the Corsican. Wherever COVID originated, the first major impact of the virus was in the Chinese city of Wuhan and since then, quarantine and lockdown, either real or potential, have dominated the lives of billions.

With more than 95 million members, the Chinese Communist Party is now the world’s second-largest political party, after India’s Bharatiya Janata Party, controlling a fifth of the globe’s population and the world’s second-largest economy. For the first time the world is seeing China setting the agenda that matters to it. It claims much of the South China Sea and has expanded internationally through the Belt and Road Initiative, which has built ports, power stations, train lines, and other infrastructure overseas.

The ruling party was established in secrecy in 1921, in the vacuum following the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912. It held its first session at a girl’s school in Shanghai, on Xintiandi, in the French Concession. The concessions to foreign powers in Shanghai highlighted China’s humiliation. It quickly moved from the school to a boat on a nearby lake to escape the attention of the police.

The birthplace of Chinese communism is now deep in the heart of one of Shanghai’s brightly lit shopping and entertainment areas, selling French designer clothing and perfumes.

When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, many pundits thought that China, the other great communist power, would be next. Understandable, but wide off the mark. President Joe Biden, at the G7 summit in June, stated not only that America had profound differences with China, but also that much of the world questioned “I know this is going to sound somewhat prosaic, but I think we’re in a contest—not with China, per se—but a contest with autocrats, autocratic governments around the world to see whether or not democracies can compete with them in a rapidly changing 21st century.”

Under Xi, the party has yet again undergone a transformation, one of many.

As Xi was preparing to take power 10 years ago, local party bosses appeared in public more like a business group, with men and women, donning sharply cut suits, shiny shoes, crisp white shirts. Expensive brandy (always French) was consumed at almost every party banquet, regardless of how modest the occasion or the surroundings. That is no longer the case. Study sessions are again mandatory where party theory and “Xi Jinping Thought” are discussed. Apps monitor the reading habits of cadres. Party bosses’ business suits have been replaced by blue zip-up jackets, white open shirts, no tie.

Xi places the onus on political loyalty and discipline. He can handle a slowing, even shrinking economy. What he fears most is a champagne-swilling Charleston-swinging economy where people forget or disregard party discipline. He has also made the selection for party membership more rigorous. Applicants must now undergo an investigation (neighbors and colleagues are asked about them) and take a battery of tests and interviews, before years of waiting for full membership. Previously, formalities could be concluded in a matter of weeks.

Over the decades, the party has adapted like a chameleon. It has survived and thrived after suppression and brutal conflict, vicious purges, famine, and political turmoil. Its secret? Simple, jettison ideology that was once at its core in favor of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” – today’s blending of rampant capitalism and the heavy hand of the state. Even communism has been ditched in favor of a Han (the largest ethnic group not just in China but the world and they make up about 90 percent of the country’s population) nationalism.

But, and this is often overlooked, Chinese citizens feel secure. Their borders are not threatened. The streets are safe. Yes, corruption is rife, the state is intrusive, connections count, favors can be bought, courts dispense party discipline and there is huge income inequality. These problems are not unique to communism. They have plagued China for millennia. But in the sweep of Chinese history, this is the blessed generation and they know it.

But this alone will not be enough to ensure stability. The World Bank considers China an upper-middle-income country and the income required to combat poverty in this category is set at $5.50 a day. China proudly proclaims that it has abolished “absolute poverty” and it has.

But according to the World Bank, about a quarter of China’s population, by this measure, still remain mired in poverty.

And income inequality is widespread as Premier Li Keqiang, who was heavily criticized at the time, pointed out in May of last year.

The Chinese dream much heralded in the early part of the last decade is now rarely mentioned. Social immobility and income inequality have markedly increased social friction. Economic stagnation is a real possibility. The world has seen China rise. It may not go into a sharp decline but its economic engines are stalling. Storm clouds do not always follow the script.