Controlled Outrage

Look no further than the newsworthy events of the past several weeks—and the attendant media and Internet discourse surrounding them—for confirmation that so-called “outrage culture” has become a permanent fixture of American socio-political dialog. The culmination of a distinctive democratic heritage of protest, freedom of expression, and the amplifying capacity of the media, this uniquely American pastime appears to have reached a new zenith in the Information Age. Whether ersatz or genuine, justified or misplaced—U.S. public outrage can be mobilized online to bring down society’s erstwhile untouchables and to shift the balance of power between social strata in a mere matter of days—a latency previously unthinkable.

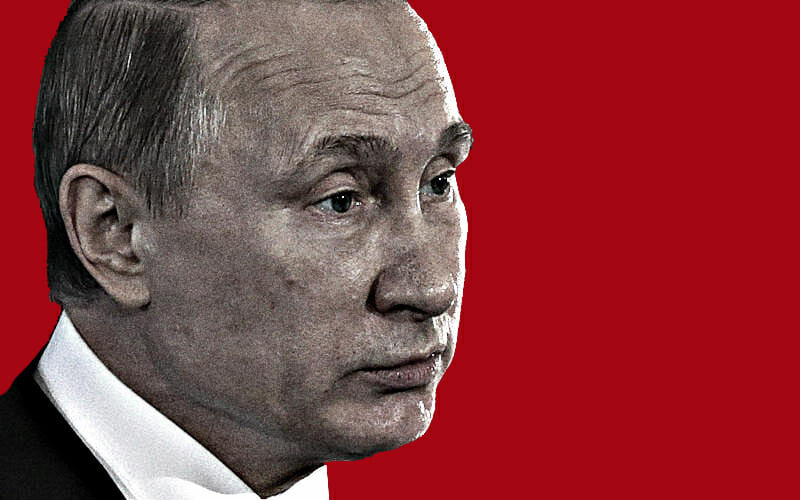

Irrespective of the merits and drawbacks of “outrage culture,” if nothing else it has become eminently predictable. Russian interference in U.S. socio-political processes has made abundantly clear that such predictability is not without implications for U.S. national security. In fact, as Russia becomes an object of U.S. outrage, the U.S. must guard against becoming the object of a classic Russian tactic: “reflexive control.”

Pioneered by theoretical psychologist Vladimir Lefebvre in the early 1960s, and adapted soon thereafter for use in classified Soviet military research, “reflexive control” theory (hereafter, RC) caught the eye of U.S. military scholars in the 1980s, particularly as Washington grappled with the question of whether Soviet overtures toward détente were genuine. An alternative to the more familiar “game theory,” which aims to predict an opponent’s moves, Lefebvre’s RC theory focuses instead on how to influence them—inducing an adversary to take a pre-determined course of action by feeding them information designed to make them do so voluntarily (and in their own minds, independently).

Timothy Thomas of the U.S. Foreign Military Studies Office at Fort Leavenworth, a leading authority on the issue, posits a classic example of RC: during the Cold War the Soviets would regularly include phony missiles in their military parades, prompting U.S. intelligence and defense contractors to chase false leads and waste valuable resources to develop more advanced analogs. RC theory, as since refined by Russian military scholars, uses a range of deceptive tools—including distraction, overload, division, and provocation—to induce adversaries to respond in ways that may appear prudent, but are ultimately pre-calculated to serve Russia’s best interest.

The merging of the uniquely American “outrage culture” with social media’s algorithmic precision provided Russia with a nearly tailor-made test bed for the tactic, as a February 16 indictment handed down by a Special Counsel Robert Mueller outlined. U.S. citizens were unwittingly induced to rally on a range of divisive issues by a group of Russian online trolls masquerading as fellow voters throughout the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. The revelation demonstrates that open societies with robust public discourse—where “outrage culture” can thrive—start from an immediate disadvantage relative to regimes that have perfected the means to stifle such discourse. To paraphrase French political scientist Suzanne Labin, who wrote extensively on Soviet propaganda techniques in the mid-20th century, the more democratic societies revere public opinion, paradoxically, the more they abandon it to enemy propaganda. “Totalitarianism moves ahead less on the conviction of its members than on the confusion of its opponents.”

Russia’s military incursions into Ukraine and its meddling in U.S. political affairs particularly demonstrate that RC remains a key part of the Russian playbook, not only in armed conflict, but in political warfare, as well. As Ukrainian specialist Maksym Bezosniuk notes, “Russia’s approach toward modern warfare has focused on attempts to achieve its dominance via information and psychological warfare by mentally exhausting the opponent’s armed forces and the targeted country’s population, without the need to deploy its military troops to achieve its political goals.” An online troll need not answer to a Russian colonel, much like a fake missile requires no Soviet aerospace engineer—but that’s essentially the point, as the same outcome is achieved.

Meanwhile, the capacity for American “outrage culture” to ultimately affect U.S. policy, on a host of issues, is definitely not lost on Moscow. Aleksandr Raskin, a Russian doctor of military science assessed in a 2015 issue of the “Information Wars” quarterly journal that “social networks present an effective instrument of control over societal consciousness, which has a direct influence on the substance of decisions by a state’s leader during periods of domestic and foreign dispute, as well as various conflicts and crises—all of which enables one to achieve superiority in information confrontation.” (Translation my own.)

Hence, while the U.S. is justifiably outraged at Russia’s behavior in cyberspace, this reflex, ironically, could prove self-defeating if not carefully calibrated. As Washington grapples with how to respond to and negotiate with Russia on cyber issues, policymakers should better understand RC theory—and America’s own unique vulnerability to it—to avoid wandering into identifiable traps. Further, given Moscow’s increased use of quasi-state and “deniable” proxies to pursue its foreign policy goals, the U.S. ought not to confine familiarity with the concept of RC solely to military circles, but should incorporate it into the conversation about broader public resiliency against Russian propaganda and disinformation.

As Peter Doran and Donald Jensen of the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) recently posited, “The Kremlin’s goal is to create an environment in which the side that copes best with chaos (that is, which is less susceptible to societal disruption) wins.” The two also prescribe broader and more robust U.S. understanding of RC as an objective of Russian disinformation, echoing Keir Giles’ 2016 assertion via Chatham House that such education ought to extend not only to “national officials and mainstream media, but throughout the society that the operation uses as its medium.” This latter distinction is critical for policymakers to understand: society itself is the medium.

While it would be an exaggeration to attribute Russia’s recent meddling in U.S. political affairs to any unified grand strategy underpinned by RC theory (Moscow’s moves are more likely the product of tactical opportunism), U.S. policymakers should nevertheless recognize the connection between Russian RC theory and America’s unique societal features, particularly as U.S.-Russian relations reach such precarious new lows. Further, Washington should follow the lead of Russia’s neighbors in breaking down the misguided distinction between the general public and the military battlefield—a distinction Russian military planners appear to have long dispensed with. As Timothy Thomas notes, “It seems that RC appears everywhere in Russia. It has a role to play as part of negotiations, long and short-term strategies, analogies, doctrines, tactics, and high-tech systems, among other areas. One should expect that the RC concept will be around long after the disappearance of not only President Putin, but more likely than not, his successor, too. RC remains a successful part of Russian philosophy and will not go away easily.”