Democrats Support Washington and Puerto Rico Statehood. Republicans Not So Much.

The U.S. Congress frequently proposes statehood bills for both Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., yet the public historically favors the former and rejects the latter. These results seem strange considering a 2017 poll found that many Americans are not even aware that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. Puerto Rico’s statehood would also have a much larger impact on U.S. politics than D.C.’s.

Puerto Rico has a population of over three million people, while the District of Columbia is home to just over 700,000—larger than only Wyoming and Vermont. Residents that live in Puerto Rico do not get to vote in national elections, nor does their one representative get to vote in Congress. D.C., although it also has no vote in Congress, currently receives three electoral votes. If granted statehood, Puerto Rico would likely have seven electoral votes.

In Puerto Rico’s history as an unincorporated U.S. territory, there have been five referendums on statehood, the most recent in 2017. Of the 23% of Puerto Ricans that participated in the vote—a historically low turnout for statehood referendums in Puerto Rico—more than 97% of them support statehood. Strong support for statehood is a result of Puerto Ricans being subject to national taxes while only being represented by a non-voting resident commissioner in the House of Representatives—their own version of “taxation without representation.” The territory, which is $129 billion in debt, is currently unable to borrow on the global market or file for bankruptcy like other U.S. states, so without statehood, Puerto Rico is in economic limbo.

Support for Puerto Rican statehood has largely been divided along party lines, according to a 2019 Gallup poll. The poll found that an overwhelming 83% of Democrats supported Puerto Rican statehood, but only 45% of Republicans agreed.

Similar to Puerto Rico, the results of a 2016 referendum in D.C. showed that residents largely support statehood. Support derives from the taxation of its residents with only non-voting representation in Congress and the fact that its statehood is already legally permissible. However, national polls from the past have consistently shown disapproval for D.C. statehood, with only 29% of Gallup’s respondents supporting statehood in 2019. Opposition transcended party lines, too, with a majority of both Republicans and Democrats disagreeing with the proposal for D.C. statehood.

To understand support for both D.C. and Puerto Rican statehood, we conducted a web survey via mTurk Amazon of 1,027 American respondents on July 7, 2020, in conjunction with the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL) at Western Kentucky University. Along with a number of demographic questions such as age, region of the country, and party identification, we randomly assigned respondents to one of two prompts so that views of statehood of one territory did not influence evaluations of the other.

Version 1: I support statehood for the District of Columbia (D.C.).

Version 2: I support statehood for Puerto Rico.

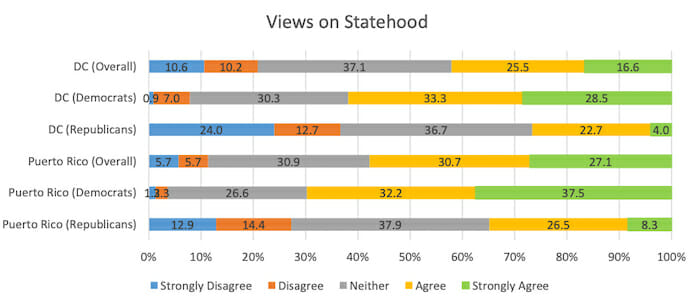

Overall, the results showed that Americans support Puerto Rican statehood over that of D.C., with 57.8% supporting the former and 42.1% supporting the latter. The margin between support for Puerto Rico and D.C. is consistent with previous trends of higher American support for Puerto Rican statehood over D.C. statehood.

Overall, the results showed that Americans support Puerto Rican statehood over that of D.C., with 57.8% supporting the former and 42.1% supporting the latter. The margin between support for Puerto Rico and D.C. is consistent with previous trends of higher American support for Puerto Rican statehood over D.C. statehood.

The most notable result from our survey is the disparity between Democratic and Republican support for statehood for both territories. The majority of Democrats showed support for statehood for both D.C. (61.8%) and Puerto Rico (69.7%), while our survey revealed that approval is still low for Republicans, with only 26.7% supporting D.C. statehood and 34.8% Puerto Rican statehood.

DC should be a state. Pass it on. https://t.co/xUJ1sud76f

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) June 25, 2020

The increase in Democratic support for D.C.’s statehood compared to previous surveys may be explained by the Democratic Party’s renewed focus on D.C. statehood during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary race. Most high-profile Democrats, including the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, came out in support of statehood for D.C. Many of these Democrats even took to Twitter in late June to voice their support for D.C. statehood just prior to a House vote on the matter in a chain of retweets reading, “DC should be a state. Pass it on.” The Democrat-ruled House voted in favor of the bill (232-180) on June 26, 2020.

Support for D.C. statehood still runs low among Americans in contrast to the majority support for Puerto Rican statehood. One reason for this could be the large distrust that Americans have in their federal government, of which they associate with the nation’s capital. Another reason could be largely attributed specifically to the Republican disapproval of D.C. statehood, caused by the aversion to giving the heavily Democratic territory a seat in the House and two seats in the Senate and constitutional concerns about local control over federal territory. With the polarization of the nation’s two parties, the recent increase in difference between Democratic and Republican support for D.C. statehood is unsurprising.

If both territories became states, D.C. and Puerto Rico would each receive two Senate seats—three or four of which would likely be won by Democrats—and a handful of House seats that would likely benefit Democrats. The new states’ electoral votes would likely go to Democratic candidates, as well, possibly swinging future presidential elections. The adoption of these two territories as states would also challenge the overrepresentation of sparsely-populated Republican states in the Senate because these small territories would add three or four reliable Democratic Senate seats, in the same way that Wyoming and Alaska reliably provide two Republican seats. This may explain the large gap between party identification and support for both territories’ statehood. Democrats are likely looking for political gains, while Republican disapproval shows fear of a political loss.

Data provided by Timothy S. Rich, associate professor of Political Science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL).