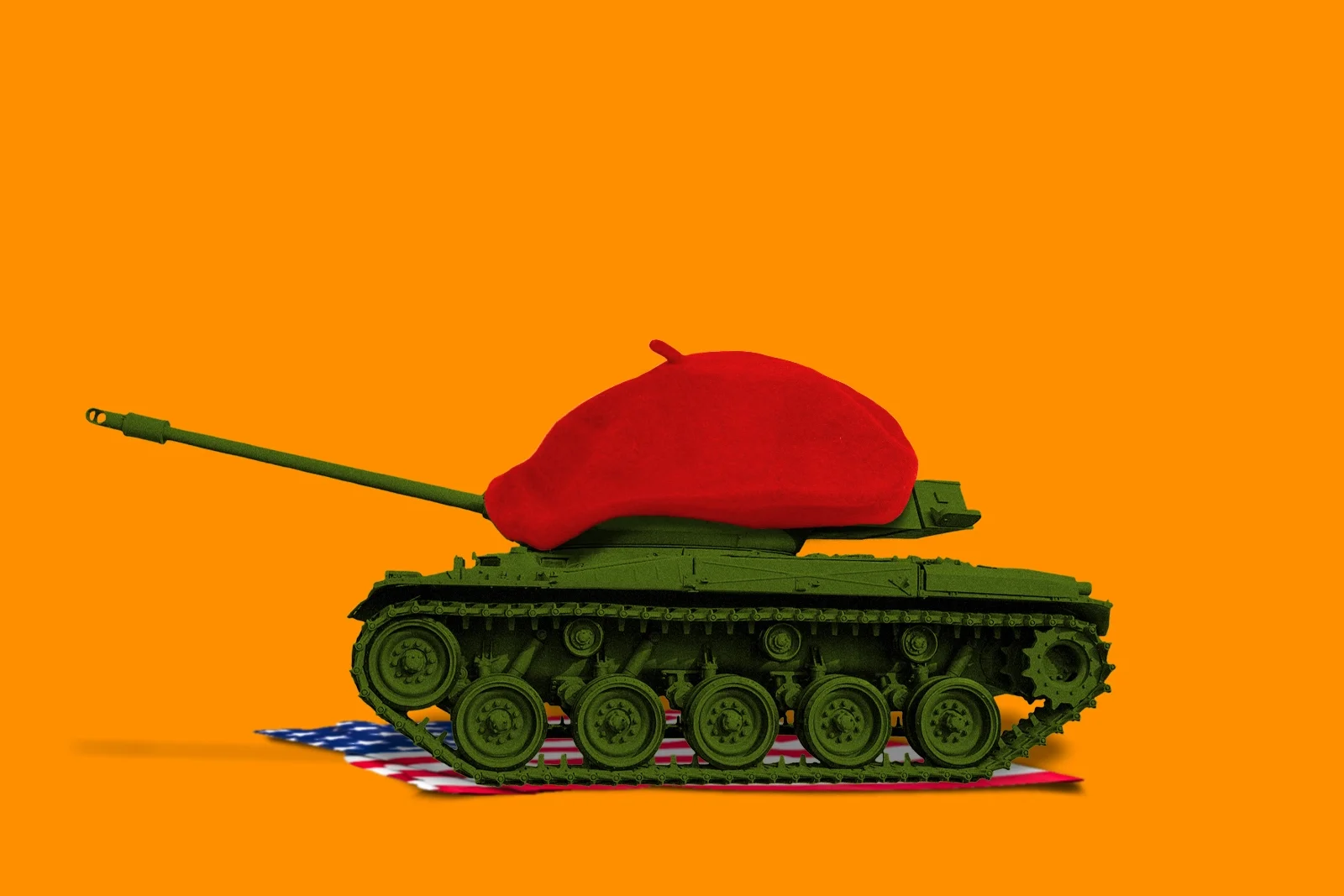

Despite Trump’s Best Efforts, Europeans aren’t Ready to Abandon America Quite Yet.

A majority of Europeans now believe their continent must prepare for war, a striking shift in public sentiment revealed in a new multi-country poll released ahead of the 2025 NATO Summit.

The survey follows President Donald Trump’s decision to bomb Iran’s nuclear facilities over the weekend, a move that has rattled global security assumptions and, in Europe, accelerated a dramatic shift in public and political attitudes toward defense.

The polling, conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), shows robust public support across the continent for increased defense spending, rearmament, and even the reintroduction of mandatory military service. It also highlights a remarkable political transformation in how Europeans perceive the U.S. alliance, their own security responsibilities, and what a credible European future might look like in a volatile new era.

Despite rising anti-American sentiment and fierce criticism of Trump from many European capitals, the survey shows Europeans are not yet prepared to fully abandon the Transatlantic Alliance. Most still see the U.S. as essential to nuclear deterrence and continental security, and there remains cautious optimism that relations can be repaired once Trump leaves office. Yet the prevailing tone is one of adaptation, not retreat.

According to ECFR foreign policy experts Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard, who co-authored the report, Trump’s return to power has already remade Europe’s political landscape. They argue the continent is undergoing a period of “political cross-dressing,” in which far-right parties have rebranded themselves as pro-Trump internationalists while centrist parties reposition themselves as defenders of European sovereignty against a hostile Washington. It is a moment, they say, ripe for reinventing European identity in a world no longer governed by post-Cold War assumptions.

The ECFR study captures a fundamental shift: the slow abandonment of Europe’s identity as a peace project, replaced by a continent accelerating its own militarization. Countries such as Denmark, Germany, and the UK now lead in support for autonomous European defense. The findings suggest Europeans are adjusting to a world where U.S. guarantees are unreliable and the EU must step up.

Conducted by YouGov, Datapraxis, and Norstat, the poll surveyed twelve countries: Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Its top-line findings are stark: 50% of Europeans support increased defense spending (versus 24% opposed); 59% back continued military support for Ukraine even without U.S. involvement; and 54% favor developing a European nuclear deterrent independent of the United States.

Perhaps most striking is the ideological transformation underway. Europe’s far-right parties have rapidly shifted from nationalism to a kind of Trump-aligned internationalism, embracing his anti-EU rhetoric and vision of a remade global order. Meanwhile, mainstream parties have grown more assertively European, skeptical of American interference, and increasingly united in calls for European strategic autonomy.

Yet the picture is nuanced. While many Europeans distrust Trump and want more continental defense capabilities, they have not fully turned away from the U.S. On key questions of deterrence and military presence, trust remains: 48% believe the U.S. still provides credible nuclear protection; 55% support continued U.S. troop presence in Europe. Moreover, 45% believe the Transatlantic Alliance can recover post-Trump, and 54% think a trade war with Washington can be avoided.

Krastev and Leonard interpret these findings as evidence of a strategic pause—a continent buying time to prepare for a leap into autonomy, even as it remains tethered to old alliances. They argue that this moment of uncertainty should be seen not as paralysis, but as possibility.

The survey finds widespread agreement that Europe must rearm. In Poland and Denmark, 70% of respondents favor increasing national defense spending, with smaller but significant majorities also supporting hikes in the UK (57%), Estonia (56%), and Portugal (54%). Support for boosting military budgets is softer but still pluralities in Romania (50%), Spain (46%), France (45%), Hungary (45%), Germany (47%), and Switzerland (40%). Italy stands apart: a full 57% oppose more defense spending, and just 17% support it.

An even more dramatic shift is visible in attitudes toward mandatory military service. In France (62%), Germany (53%), and Poland (51%), majorities support its return. Support drops in Hungary (32%), Spain (37%), and the UK (37%)—though the question wasn’t asked in Denmark, Estonia, and Switzerland, where conscription remains in place. The generational divide is stark: over half of Europeans aged 60 and older support conscription (54% of those aged 60–69, 58% of those 70+), while only 27% of 18- to 29-year-olds—those most likely to be conscripted—share that view. A majority (57%) of young adults oppose the idea outright.

One area of relative consensus remains: unwavering support for Ukraine. Even amid uncertainty about continued U.S. backing, Europeans across the board want to keep up military and economic pressure on Russia. In eleven of the twelve countries surveyed, majorities or pluralities oppose reducing military aid to Kyiv, pushing Ukraine to cede territory, or lifting sanctions on Moscow. The strongest support for a firm line against Russia comes from Denmark (78% favor continued support even if the U.S. pulls back), Portugal (74%), the UK (73%), and Estonia (68%). Similarly, those countries are also the most opposed to pushing Ukraine to negotiate away occupied territory or to lifting sanctions should U.S. policy shift.

That enduring solidarity with Ukraine contrasts sharply with views of America itself. Across Europe, Donald Trump’s resurgence has rekindled skepticism toward the U.S.—and in some quarters, outright hostility. In Denmark, a striking 86% of respondents now believe the U.S. political system is “broken,” up from 54% six months ago. In Portugal, the number stands at 70%, up from 60% in 2020. Majorities in the UK (74%) and Germany (67%) agree. Even in historically pro-American Poland, disillusionment is rising: 36% now describe the U.S. system as broken, up from just 25% in 2020.

Amid this transatlantic unease, Europeans are unsure whether the EU can—or should—go it alone. In Denmark and Portugal, half of respondents believe that EU strategic autonomy on defense and security is achievable within five years. But in Italy (54%) and Hungary (51%), majorities say such a goal is either “very difficult” or “practically impossible.” In other countries, opinions are split. France, Romania, and Germany show roughly equal parts optimism and pessimism, while in Poland, Estonia, and Spain, more people doubt EU autonomy than believe in it. Likewise, the belief that the EU can emerge as a global economic and political rival to the U.S. and China remains a minority view in all but one country surveyed—Denmark.

Yet despite the criticism of Trump, many Europeans remain confident in the foundational elements of the transatlantic alliance. Across the twelve countries polled, 48% of respondents believe Europe can continue to rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Fifty-five percent support maintaining an American military presence on the continent, and 54% think a trade war with Washington can be avoided. There is also a widespread belief that once Trump leaves office, the relationship will rebound. That sentiment is most pronounced in Denmark (62%), Portugal (54%), Germany and Spain (52%), and France (50%). By contrast, in Hungary (20%) and Romania (28%), fewer expect significant improvement post-Trump. And in only a handful of countries do more than a quarter believe Trump has permanently damaged the transatlantic relationship.

Still, Trump’s return to power is having profound knock-on effects—geopolitically and ideologically. The report argues that Trumpism has catalyzed a reordering of Europe’s political spectrum. Populist parties, once defined by their anti-establishment stance, now often align themselves openly with Trump’s worldview. Meanwhile, mainstream parties are recasting themselves as defenders of European sovereignty—not just against external threats like Russia, but against Trump’s brand of politics.

This shift has reshaped perceptions of the U.S. across partisan lines. Voters for far-right parties like Fidesz in Hungary, PiS in Poland, the Brothers of Italy, AfD in Germany, and Vox in Spain tend to view the U.S. positively. Their counterparts in mainstream parties, however, are increasingly critical of America’s political dysfunction. That inversion has turned the U.S. into a proxy for broader arguments about the EU itself. In Poland, Spain, and Portugal, majorities of voters for PiS, Vox, and Chega, respectively, now say the EU is “broken”—a sentiment that was previously limited to a minority.

Conversely, voters for centrist parties have become more overtly pro-European, especially in Germany and France. The result is a striking reversal: America, once the aspirational model for many Europeans, is now increasingly embraced by the populist right, while Europe itself becomes the rallying point for liberal centrists.

Mark Leonard, the ECFR’s founding director and co-author of the report, describes the moment starkly: “Donald Trump’s revolution has come to Europe – overturning its political and geopolitical identity. Our poll shows that Europeans feel unsafe and that Trump is driving demand for increased defence spending, the reintroduction of military service, and an extension of nuclear capabilities across much of Europe.”

Leonard adds that Trump’s influence mirrors the destabilizing effect Brexit had on British politics. “He is also transforming domestic politics in a similar way to Brexit. Far-right parties are no longer simply seen as anti-system; they have become part of a pro-Trump internationale. On the other hand, many mainstream parties are reinventing themselves as defenders of sovereignty against Trumpian chaos.”

Ivan Krastev, the report’s co-author and chair of the Centre for Liberal Strategies, draws an even sharper contrast. “The real effect of Trump’s second coming is that the United States now presents a credible model for Europe’s far-right. To be pro-American today mostly means to be sceptical of the EU, to be pro-European means being critical of Trump’s America.”

In other words, Europe’s political compass has flipped—and the needle now points to Washington not as a lodestar, but as a lightning rod.