Geographical Divisions of Colonial Nicaragua: Impacts on Development in the Indigenous Territories

The eastern coast of Nicaragua is divided into two autonomous regions, the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCN) and South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region (RACCS). Together, they serve as sovereign territory for Nicaragua’s indigenous populations, including the Miskitu, Mayanga, Rama, and Garifuna. Together, the RACCN and RACCS are the most underdeveloped parts of Nicaragua, in large part due to scant social and economic investments, a relatively weak transportation and communication infrastructure, citizen insecurity, relatively low coverage of basic services, and protracted tensions with western Nicaragua.

The following study traces the path that connects colonization (and decolonization) of Nicaragua to the present-day sources of underdevelopment for these two autonomous regions. A history of this development, from colonization to today, encapsulates much that international theories of development have to offer, from geography’s impacts on development and colonialism to the sociocultural construct of the “west versus the rest” attitude. This is what makes Nicaragua, and more specifically the RACCN and RACCS, such a fascinating case-study. The entire post-Colombian history of the country and the divergent developmental trajectories between the east coast and the west coast begin with a fortuitously positioned mountain range that splits Nicaragua in two.

Pre-Colonial History

Nicaragua in its pre-colonial days was very similar to the rest of Latin America. Populations of Chibchas and Nahuatl (linguistic relatives of the Aztec and Maya) had assembled egalitarian societies that were unrestrained by political and social hierarchies. Lands were communal property and the products of agricultural labor were spread equally within a community. Descendants of Mexican origin populated the central highlands and Pacific coastal regions (near the present-day capital of Managua) while most of Nicaragua’s Caribbean lowlands were populated by migrants who had traveled north from present-day Colombia. Before the first European ever stepped foot in Central America, the familial lines of indigenous Nicaraguans traced back nearly 10,000 years…It is safe to assume that none expected the day would come that they would be demoted to “unwelcomed visitor” on their own lands.

West Coast Colonization

Although not the focus of this study, a brief history of Nicaragua’s colonial west is germane because it helps to highlight the consequences of Nicaragua’s bipolar colonial paths. Spain arrived in Central American in 1502 and by the middle of the century had successfully colonized most of Central America, including present-day Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and parts of Southern Mexico. The first conquest into Nicaragua began in 1520 was by conquistador Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, the founder of Granada and Leon. Yet, instead of incorporating all the Nicaraguan territory under the Spanish Empire, the Spanish conquistadors left the entire Caribbean (eastern) Coast untouched. Spain’s expansionary efforts ceased when it reached the mountains connecting Lago (Lake) Cocibolca with neighboring Honduras.

There are two reasons that might explain why. First, the mountains created a natural barrier that, if crossed, posed greater risks to the small number of Spanish conquistadors than it did rewards. Second, the Spanish were inexperienced in colonizing (i.e. conquering) decentralized indigenous populations, of which the east coast was a considerable harbinger. Nicaragua had essentially been split in two, the consequences of which paved the way for centuries of political, social, and economic divisions between east and west Nicaragua.

Fortunately for the Spanish, the west coast, although scarce in mineral and agricultural resources, was inhabited by a large indigenous population. The Maya and Aztec would soon be exploited for slave labor and sent to the South American mines of Peru and Mexico. The subjugation, enslavement, and diffusion of European diseases led to a near complete annihilation of the Aztec and Maya populations (from 600,000 in 1523 to 30,000 in 1544). As the natives perished they were quickly replaced with mixed Spanish and indigenous mestizos. This practice of exploitation would persist until Nicaragua declared its independence from Spain in 1838.

East Coast Colonization

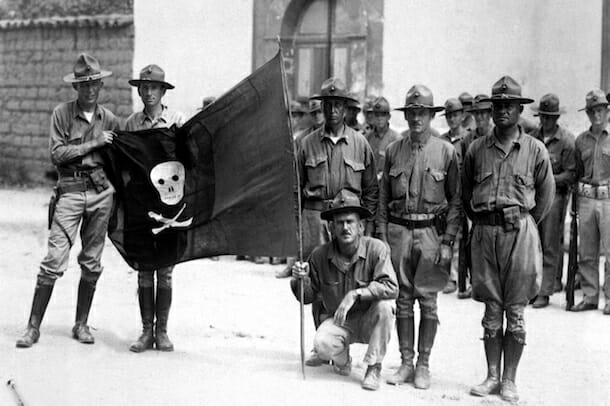

The colonial void left on the east coast was not filled until the beginning of the 17th century when British pirates arrived and transformed the territory to serve as their naval base and gateway into Latin America. The British eventually claimed the entire Caribbean Costal region, later referred to as the more appropriately-named, Mosquito Coast (site of present-day RACCN and RACCS). The arrival of the British marked the beginning of a two-century-long relationship between the Miskitu Indians (as well as other, lesser populated Indian tribes) and the British Empire.

By 1687, the Mosquito Coast was under British rule, along with the Bay of Honduras and Panama, and an Anglo-Miskitu alliance was formed after the creation of the Kingdom of Mosquitia and the crowning of the first Miskitu King. From a bird’s eye view it would have been obvious that the colonial paths of the east and west coasts were running further and further apart. Whereas the Spanish had fashioned a bustling slave market that led to the evisceration of an entire population of native Nicaraguans, the British leveraged the Mosquito Coast’s resource-rich environment to augment its economic interests. Unlike in the east, the Natives were treated more like partners than as slaves. Trade relationships were established between the Miskitu and the British that included the exchange of military and diplomatic protection for mahogany, gold, rubber, turtle, and guerilla fighting to suppress the encroachment of other imperial powers. This relationship culminated in the genesis of a complex, multi-ethnic political, economic, and social culture.

The relationship in this form lasted for nearly one and a half centuries, until Britain, eager to affix itself permanently in the region, formally recognized the Mosquito Kingdom as an independent state in 1837 (Recall that in 1838, Nicaragua had declared its independence from Spain and subsequently vied for sovereignty over the Mosquito Coast regime). Although the Kingdom was recognized as an independent state, Britain did not engage in a full recognition of indigenous self-determination. Instead of offering independence and granting land titles to the indigenous population, Britain offered land rights to woodcutters, traders, and businessmen, extending and exacerbating the indigenous plight for sovereignty on its home land. Not coincidentally, recognition of Mosquito Kingdom overlapped with the declining supply of Mahogany, one of Britain’s most profitable exports from Central America, in Belize. Britain’s renewed presence inspired the introduction of foreign involvement in the form of financial capital and immigration, primarily from the U.S., Europe, the West Indies, and China. In response to the U.S.’s territorial expansion (Manifest Destiny), Britain consolidated its hegemonic presence over the region by establishing a protectorate over the Mosquito Kingdom.

After only twenty years of partial-sovereignty, the 1860 Treaty of Managua between Nicaragua and Great Britain stripped Mosquito Kingdom of its independence and recognized Nicaragua’s sovereignty over the territory. The Treaty left an even smaller patch of land near Bluefields for the Miskitu to call their own. Indigenous sovereignty was still out of reach, however, because the British had established what was essentially a proxy-colony on the Mosquito Coast to safeguard its piece of the international mahogany trade market.

The relatively harmonious relationship between the indigenous population and Britain was permanently disrupted in 1894 as power shifted away from British colonialism towards U.S. economic exploitation. Companies from the United States were causing permanent damage to indigenous lands via their extraction methods and had monopolized the workforce by driving most other industries into the ground. As a result, Miskitu and Mayanga Indians had no choice but to accept the low-wage, taxing jobs they were offering. Connected to the rise of U.S. economic involvement was an equally powerful threat to the Miskitu’s cultural heritage and regionally dominant racial status. For instance, U.S. companies favored English-speaking Creoles from the West, which served not only to discourage the use of native languages but also to restrict the finite number of jobs to a growing supply of outsider laborers. The final blow to the indigenous peoples’ remaining semblance of sovereignty was the annexation (despite their pleas to Britain for military support) of the Bluefields area of the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua by President José Santos Zelaya. A unified Nicaragua allowed the United States to broaden its presence, and in 1912 it established a military occupation that lasted for over twenty years.

With the Mosquito Coast region officially part of the Nicaraguan state, tensions that may have remained idle otherwise began to surface. The indigenous people still claimed sovereignty over the land on which they lived, yet over time the U.S. (and the U.S.-backed regime in Nicaragua), had pilfered the region with such devastation that it was nearly impossible to be revived in a short amount of time. Additionally, infighting between the West (the modern part of the country inhabited by the Mestizo, European-Latin descendants) and the East (home to the indigenous Native Americans) became a constant reminder of the differences between the two regions. These social, cultural, and economic tensions between west and east Nicaragua would continue to flourish into and after the Sandinista Revolution.

On the Revolution

As revolutionary fervor in Nicaragua became more and more popular during the 1950s and 1960s, U.S. companies began parting from the area, leaving the Mosquito Region with no infrastructure, the Miskitu and other native groups with no “modern” vocational skills, limited farmable land, and a lack of political representation. Had the (colonially-derived) tensions between the west and the east not been so aggressive, perhaps the nation would have united and its resources been shared more equally across the region. But this was not the case, and because of the distinct east-west division, there were also perceived divisions between the people of the west and the people of the east. The country was divided, and there was little, if any, trust between the two camps. Western Nicaraguans believed that the Miskitu were acting as pawns for the British Crown, while the Natives’ mistrust was rooted in the intensely-held (and largely accurate) belief that the west had no interest in protecting their rights.

As Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas began to rally Nicaraguan peasants to overthrow the Somoza government, the indigenous people did not occupy even an after-thought in the minds of the Sandinistas. Weary of the implications of a Sandinista government, many of the Miskitu joined forces with the U.S.-backed contras to thwart the revolution’s success. Subsequent infighting between the natives and the Sandinista government was a common theme in Nicaragua after the Sandinistas successfully ousted the Somoza regime in 1979 (it was also one of the main drivers of the revolution’s collapse after only eleven years). The relationship between the Natives and the Sandinistas suffered throughout the life of the revolution. None of the revolutionary campaigns that the Sandinistas implemented helped the native populations. In fact, many of them did just the opposite.

The Sandinista’s literacy campaign only taught Spanish, and land titles that were formerly under U.S. ownership were not returned to the indigenous populations. The indigenous continued to riot against the revolutionary government, so in 1987, as a measure to engender peace between the east and the west, Daniel Ortega signed the Autonomy Law of the Atlantic Coast to address the concerns of the indigenous populations and to establish the RACCN and RACCS.

Present day development issues

Nicaragua is one of the poorest and most underdeveloped countries in the world, and the RACCN and RACCS rank even lower. For instance, the average poverty rate for both autonomous regions is 68.8%, 10 points higher than the national average. Only 45% of the population between ages 15-24 has at least a fourth-grade education, and illiteracy affects nearly 55% of the population, whereas the country average is only 24.5%. Local industries have yet to be replaced after the war in the 1980s, and unemployment levels vary between 50 and 80% higher than the rest of the country. Transportation costs are also higher in the East and as a result the cost-of-living has risen to an unmanageable level. There is a substantial lack of infrastructure and poor access to safe drinking water, electricity, and means of sanitation. Lastly, the locations and lack of law enforcement has made the two autonomous regions ripe for drug trafficking, pushing crime rates well above average levels (especially in the RACCS where the murder rate was estimated to be 42.5 per 100,000 in 2011).

To understand why the development of the eastern region of Nicaragua has followed such a different path than the west, one must study the country’s colonial history. The driving force of the original east-west division at the moment of colonization was geography. Yet, the expression of these divisions has been cultivated in response to the consequences of the original east-west divide. For instance, the Aztec and Maya were quickly wiped out and replaced with a more privileged race of Nicaraguans of European blood. Eastern tribes, however, were fortunate enough to maintain their familial lineage, but it appears that this has come at a cost. Because indigenous people are considered to be of lower-class, lower intelligence, and less capable of self-determination, they are either a) ignored (as in the Miskitu and other Native Nicaraguan populations), or b) conquered (as in the Maya and Aztec of eastern Nicaragua). Thus, one can easily trace the path between colonization (and decolonization) of Nicaragua to the underdevelopment of Nicaragua’s indigenous regions.