Iran, the Revolution and the Language of War

A few days ago, I revisited a lecture given by Fred Halliday, FBA (Fellow of the British Academy), an intellectual giant among scholars of Middle East and Cold War history, at the London School of Economics in 2009. His topic was “The Islamic Republic of Iran After 30 Years.” For nearly a quarter century, Halliday was professor of International Relations at the LSE and recognized worldwide as a leading expert in the study of Islam, the Middle East and great power relations in the region.

He died just over a year ago, but for more than three decades before that he was also in great demand in media outlets, including the BBC World Service at Bush House, my professional base next door to the LSE. He often came to take part in World Service programs and I came to regard Fred as a friend. Watching him interpret the Iranian Revolution thirty years after was an enlightening experience once again. An important lesson I have learned in my life is to engage the best when in doubt. For me, going back to Fred Halliday was prompted by a recent experience during an exchange about an article I had written on Iran. My exchange was with an editor. Young, bright and overbearing on this occasion, he thought I was giving Iran a mild treatment, otherwise widely denounced these days as a “dictatorship” representing dark ages and which threatens the world.

Needless to say, I am one of those who do not subscribe to this version of history, past or present. The world is much more complex. It is tempting and easy to grab a news agency copy and throw it at someone to prove our own view of events, based on a narrow interpretation of recent knowledge and conventional wisdom of the present time that is temporary by its nature.

It is worse when the agency report thrown at the person contains claims made on a website by one side about casualties at the hands of the other, with no way of checking independently. Anyway, I moved on without rancor on my part. To recognize, indeed to reflect with caveats, the significance of a propaganda war is one thing. It is quite different to be blown away by a current political storm when the objective is to attempt a serious historical analysis.

Halliday had a remarkable capacity to interpret. He used to speak of similarities between the world’s major revolutions in the twentieth century: the Russian (1917), the Chinese (1949), the Cuban (1959), the Nicaraguan (1979) and the Iranian Revolution in the same year. It is a mistake to regard the point in time of a revolution as “Year Zero” and insist that all bad things follow. Neither the claim that “everything has changed” nor that “nothing has changed” is correct. The culture of a country that undergoes a revolution does not change at once.

The truth is very different. As Halliday would say, revolutions are extremely messy phenomena. They involve great chaos, cruelty and generosity. That chaos and cruelty precedes revolutionary upheaval, as well as follows. Revolutions represent dreams, hopes and disappointments. However, they occur because of the fragmentation of societies and exclusion of important sections of populations. There are both internal and external factors responsible for revolutions. Often, the outcome is a realignment of forces. Beneficiaries of the past become losers; victims, at least some of them, gain.

No revolution, as far as I know, has achieved all that it promised. A revolution is a response, rather than a solution, to the problems that triggered it. In Iran’s case, there had been years of repression under an absolute monarch who was installed by external powers following an Anglo-Soviet invasion in 1941; an Anglo-American intelligence plot that overthrew an elected government in 1953; gradual fragmentation of a traditional society and exclusion of important sections thereof, the clergy and the traders in particular; severe restrictions and coercion directed at the opposition; the offense and the suffering caused by the Shah’s dreaded secret police SAVAK (1957–1979), established by the United States Central Intelligence Agency and Israel’s Mossad.

Suppression of liberals and others on the Left, like the Tudeh (party of the masses), had gone on under the monarchy in Iran. Tudeh supported the 1979 revolution while others on the Left opposed it. However, the alliance between the Tudeh Party and Iran’s emergent ruling clergy collapsed in the early 1980s. Then it was back to the past. For the leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the United States was the “Great Satan,” and Iran had to follow a course that was neither East (meaning Russia) nor West. America was held responsible for what went wrong in Iran in the decades before the overthrow of the Shah. Also, the fact that the Soviets had invaded Iran should not be forgotten.

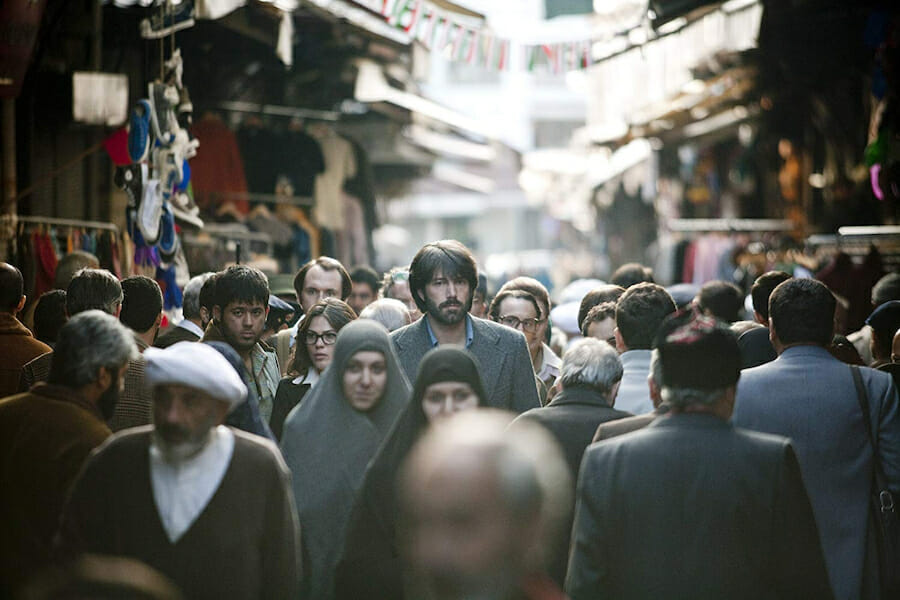

We are into the fourth decade since the founding of the Islamic Republic. It has been a long period of crisis between Iran and the West, with some notable exceptions: the Iran-Contra affair involving the Reagan administration flirting with the Iranian regime to facilitate arms sales to its military to fund Nicaragua’s rightwing Contra guerrillas in the 1980s while the United States was also supporting Iraq that had invaded Iran; during the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and for a short period thereafter; and Iran’s acquiescence to getting Shia militias to cease fire in the Iraqi conflict. Each time, hopes of reconciliation between the two bitter enemies were dashed. We are now at a point where war clouds are looming.

Despite all that is said about the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, it was, in fact, a very modern revolution. It was a populist response to an unpopular ruler. Nothing illustrates it better than the way the Shah’s armed forces collapsed in the end. More than thirty years on, we see men and women mixing in Iranian society at the workplace and in the streets. Women learn and teach with men at co-educational institutions. Iranian scientists are engaged in research in medicine, other scientific and technological fields and, more controversially, in the nuclear program.

Is Iran a dictatorship? Power certainly resides in Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Guardian Council, the president, the Majlis (parliament) and institutions like the judiciary. It is more dispersed than we are led to believe. There are instances of strong-arm tactics against some opponents and publications regarded as “outside the system,” for instance during and after the 2009 presidential election. But other critics have a surprising degree of freedom to express dissent––more than in some neighboring countries in the region.

Have miscalculations and errors of judgment been made? Sure. The Carter administration’s support in the late 1970s until the very end of the Shah’s regime was one such error; and the American hostage crisis (November 1979–January 1981) at the U.S. embassy in Tehran was a miscalculation which sealed the fate of Carter’s presidency, ensuring the victory of Ronald Reagan and all that followed in the 1980s. Opportunities have presented themselves in the last thirty years for Iran and the West to improve relations, only to be lost.

Where is Iran’s nuclear program going? I do not know. Nor do in my view most other people who talk endlessly in the media about the Iranian threat and how to deal with it. Despite the amount of coverage, Iran’s nuclear program remains a subject of inference, speculation and conspiracy theories. The Iranians have before them examples of China, North Korea, India and Pakistan. They know realpolitik. A nuclear power has a greater sense of security and others look up to it. Given the past and the present, the idea of their country having nuclear weapons is popular among Iranians. If one were to make a guess, it would be that Iran would probably want to acquire the capacity to make the bomb, but would not actually go ahead unless it was felt in Tehran that external events warranted that step.

As the governments in London, Paris and Washington continue to play the game of brinkmanship, wiser heads have warned against the current dangerous path and have advised engagement with Iran. At a recent conference at the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London, former British ambassador and one of the foremost Iran experts, Sir Richard Dalton, was very critical of the West’s policy on Iran, in particular of the British foreign secretary William Hague. Lord (Norman) Lamont, former Conservative chancellor of the exchequer, agreed. But in the light of escalating rhetoric and military maneuvers, the prospects of the situation taking a ruinous turn are real.