Opportunity Lost or Covered – Nairobi Court Acquits Chinese National of Wildlife Trafficking

It could have been the proverbial pot of gold. Instead, it became at best, an opportunity lost in the fight against transnational organized wildlife crime. On February 2, a Nairobi area court acquitted Hoang Thi Diu, a female of apparent Vietnamese/Chinese dual citizenship, of charges relating to the dealing and possession of 145 kilograms of ivory, rhino horn, lion’s teeth, and claws.

Objectively, and considering the evidence before the court, the verdict was not incorrect. Evidence not presented, evidence that was contradictory, evidence not challenged, and evidence that was tainted, led the court to the only conclusion to be made.

It began with the sudden and unexpected death of 58-year-old Chinese national, Yang Chang Gui, in the early morning of November 16, 2022. Hoang Thi Diu, who had been given a spare bedroom for a temporary stay, became concerned when, in the early morning, Yang Chang Gui was not answering his continually ringing mobile phones. When she went to investigate, and with the assistance of the building caretaker, they discovered that Yang Chang Gui had seemingly passed away in his sleep.

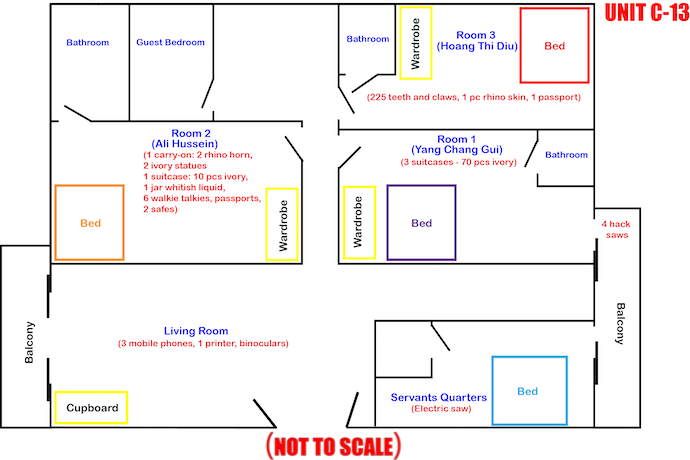

The police were called to the spacious 3-bedroom apartment on the periphery of Nairobi’s Chinatown and in the process of what was surely expected to be a routine investigation, discovered under the bed of the deceased, three suitcases filled with cut-to-size elephant tusks.

Subsequently, the rest of the apartment was searched and more wildlife trophies and cutting tools were discovered. In the master bedroom was one suitcase with ten pieces of ivory, one piece of carry-on luggage with two rhino horns and two small ivory statues, six walkie-talkie-type devices, binoculars, and a large jar with a whitish liquid that was never identified. In the third bedroom, the bedroom of Hoang Thi Diu, a wrapped bag of lion’s teeth and claws was found. In other areas of the apartment, four hack saws and an electric saw.

On the face of it, the police had inadvertently come across a wildlife trophy consolidation point, a location where wildlife trophies were prepared for their export from Kenya and almost certainly through Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. Investigators had been presented with a serendipitous opportunity to crack an organized crime group’s wildlife trafficking pipeline in and out of Kenya.

By the time the investigation was complete, however, only Hoang Thi Diu, the short-term roommate who came across the deceased, had been charged. The subsequent trial testimony painted a picture that left more questions than answers, a common characteristic where transnational organized crime and the criminal justice systems go head-to-head. Invariably, in this part of the world, the criminal justice system is the also-ran.

The court was told that Yang Chang Gui had been living in Apartment C13, Sunshine Court, Lavington, for some years, but the number was never quantified. He died from causes never revealed to the court, and the presiding magistrate, Principal Magistrate Gideon Kiage of Kahawa Law Court, left to presume that his passing was not an obvious homicide.

The court was also informed that approximately 28 units of the 50-unit structure were owned by the South Sudanese government and not surprisingly, most of the residents of those apartments were from South Sudan. The deceased reportedly came into his particular apartment when the previous tenants had defaulted on their rent.

Courtroom testimony indicated that it was Yang Chang Gui’s older brother, now living in China, who had initially signed for the apartment and was presently paying the monthly rent; the deceased only paying for the electricity and water. There was never an indication as to whether Yang Chang Gui was gainfully employed and his immigration status in Kenya was never specified.

Courtroom chitchat labelled Ali Hussein as a medical doctor but that was never confirmed. Testimony from the witnesses differed slightly, but it appeared that his room contained the rhino horn, two small ivory statues, six communication devices, binoculars, a large jar with a whitish liquid that was never identified, two safes, 2 to 3 passports, and possibly an air boarding pass.

Whether Ali Hussein lived in the apartment on a full-time or part-time basis was a question never definitively answered. Two of the prosecution witnesses, who were employees of the apartment complex, and the accused, testified that he was a close associate of the accused and lived there essentially on a full-time basis since at least 2021.

Inoti informed the court that after the initial seizure, an immigration alert had been put out for Ali Hussein and he was subsequently arrested at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport coming off an inbound flight. Hussein was arraigned at Kahawa court and in custody for a short period while an investigation was conducted. This included taking him back to the crime scene. Inoti told the court that the investigation cleared Hussein of any involvement in the criminal activity under investigation. He also said that the decision not to charge was made by prosecutors based on the fact that Ali Hussein was not at the scene at the time of the discovery.

The enigma surrounding the deceased and Ali Hussein was matched by that of Hoang Thi Diu. On her initial arrest, police announced that she was a Chinese national with a Chinese passport. Her charge sheet before the court indicated she is a Vietnamese national with a corresponding passport. She told the court in her defense that she had arrived in Kenya from Angola on August 29, 2022, looking for a sister who had run away with a boyfriend who had not been approved by the family. Inoti stated that her entry date was September 3.

She stayed initially at a 4-star hotel with a casino for about 10 days but found it too expensive ($100 per night). While searching for cheaper accommodation, she was introduced to the deceased at the hotel-casino, a casino she had also been led to believe was frequented by her runaway sister. The accused continued by telling the court that the deceased agreed for her to stay in his third bedroom until the permanent room occupant returned. She never touched any of the occupant’s possessions and never saw the ivory or rhino horn in the apartment while she was there. The court was not advised as to whether her sister had ever been located.

While Hoang Thi Dui’s version may have been saleable to someone who knew nothing of the case, it had been already muddied by the testimony of a previous witness. A Chinese national, living just outside Nairobi, testified that he had been contacted by the deceased’s brother to make the appropriate funeral arrangements and alluded to the court that the accused may have been working as an escort.

In addition, Hoang Thi Diu was seemingly provided a deference by the court during the entire court process. It began with her bail. Hoang Thi Diu, in Kenya from Angola, would surely have been a significant flight risk but was released on a cash bail of $1,300 with one passport being held by the court.

After her first lawyer withdrew from her case (Edwin Motari reportedly came by way of the Chinese community and had been previously arrested by masquerading as a lawyer), the court itself found a second lawyer to act on the accused’s behalf on a pro-bono basis. That arrangement fell through, and another pro-bono advocate was found.

Her trial was completed in 14 months, taking half the time typically seen for a similar matter. The court sat on 37 occasions to hear eight witnesses during that time. This trial also featured an atypical change in magistrates when Senior Resident Magistrate Boaz Ombewa went on leave and was replaced by Principal Magistrate Gideon Kiage. Far from being a humble single woman looking for a runaway sister, one could not be faulted for believing she was in Nairobi at the bidding of someone else, perhaps as an ‘escort’ and/or a wildlife trophy ‘mule.’

And what of the mobile phones of the deceased, the ones who according to the accused were ringing in the sitting room, alerting her to the fact that something was not right with the deceased? They were seized by police but did not make it to the inventory list submitted to the court. It only came out in cross-examination that a second inventory had been prepared for court purposes that omitted the seizure of three mobile phones and a printer. Chief Inspector Inoti later testified that the phones had been left off the ‘amended’ inventory as they were deemed not relevant to the matter before the court.

Could this not be a case where their irrelevance made them relevant, perhaps even exonerating the accused? And because the phones and printer were left off the inventory, the court was given no indication as to whom they were registered.

In September, in another Nairobi courtroom in another ivory trial, Senior Principle Magistrate S.O. Temu asked rhetorically to the same Chief Inspector Inoti, “You people go for small operators covering the people involved in these wildlife crimes. How do you want the courts to help in ending the trade, while the KWS don’t give us the big guys?”

Is this not a similar circumstance to the acquittal of Hoang Thu Diu and the exoneration of Ali Hussein? Stakeholders and the public are left to believe that Yang Chang Gui was solely responsible for the wildlife trophy collection point in Apartment C-13; that he kept wildlife trophies, communication devices, and cutting tools essentially all over an apartment shared with two other people, one who had been living there for some time.

Is it possible? Yes, it is possible. We have no idea as to the outcome of investigations completed; whether the working CCTV system of Sunshine Court was examined, whether the cleaner of Yang Chang Gui’s apartment C13 was interviewed, or whether the security agency responsible for the compound were consulted or their vehicle registry checked.

But is it likely? No. Is it believable? No, certainly not when all the facts are examined in concert.

We have a Nairobi apartment located on the periphery of Chinatown, being occupied by a Chinese male for several years with no visible financial means, living in an apartment owned by the South Sudanese government, with rent being paid by someone in China, found with 80 pieces of ivory in his apartment (or 78 pieces, police testimony differs), cut to size in suitcases, two rhino horn, 225 teeth and claws of leopard, lion, baboon and one piece of rhino skin, 6 walkie talkies, saws, a printer, checkbooks, two safes, company seals and stamps.

In addition, the original responding officer omitted to include in his written statement that he found, what were believed to be lion teeth and claws, in the bedroom of the accused, and that both Ali Hussein and Hoang Thi Diu had at least two passports each, that three mobile phones found in the apartment of the deceased were deemed irrelevant before the court, and that a second inventory provided to the court did not include these three phones or a printer also found in the apartment, and that the trial time was at least half of what is typical.

An opportunity lost or covered?