Pakistan’s Long War With Its Own Proxies

Terrorism in Pakistan is not a distant headline—it runs through daily life. Families in Peshawar still mourn children lost in school attacks; shopkeepers in Quetta eye markets that could explode without warning; parents in the former tribal areas live with the constant dread of roadside bombs. This is not merely a security problem. It reflects deep political, social, and economic fragilities. Unlike Afghanistan, where militancy thrives amid state collapse, or Iraq, where violence is driven by sectarian polarization, Pakistan’s militancy is both homegrown and the product of decades of statecraft.

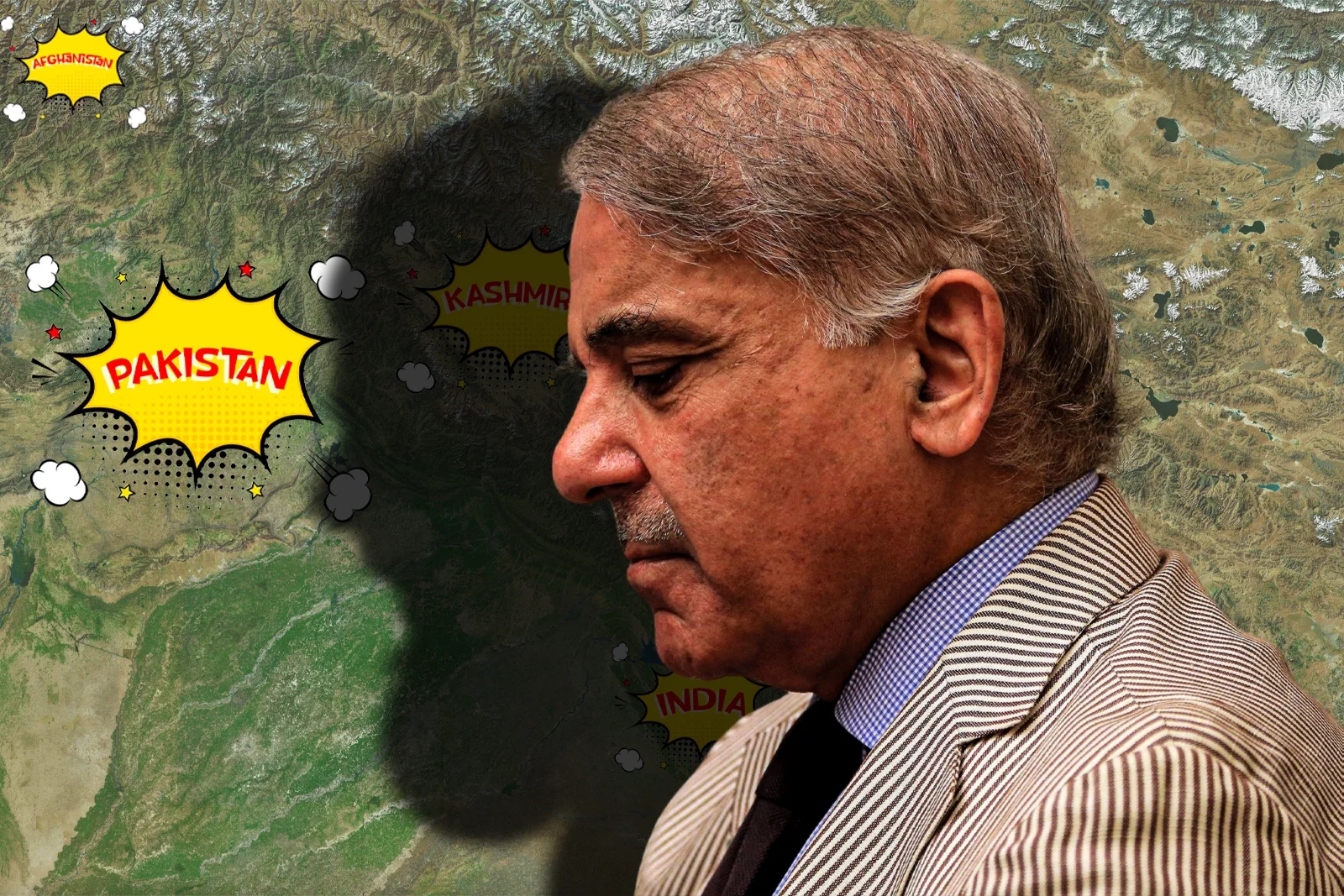

For years, Islamabad has cast Kashmiri insurgents as freedom fighters resisting Indian occupation—a cause it has openly supported. To many Pakistanis, this stance expresses solidarity with a people seeking self-determination. But the line blurs when groups initially cultivated for that theater evolve into transnational militants. Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, for instance, extended their reach beyond Kashmir, carrying out attacks across borders and, at times, threatening Pakistan itself. The “freedom fighter” narrative resonates at home, yet it also entrenches militancy as an instrument of policy, complicates Pakistan’s international standing, and paradoxically undermines its internal stability.

The Pakistani Taliban, or Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, poses the more immediate danger to ordinary citizens. Unlike Kashmir-focused groups, the Pakistani Taliban targets the Pakistani state itself—soldiers, police, and civilians. Its resilience has been amplified by safe havens in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, where cadres regroup and strike with relative impunity. For families, this creates a familiar uncertainty: Will the next bomb hit a neighborhood street, a market, or a school? Pakistan is trapped in a bitter paradox—fighting some militants while others exploit regional geopolitics to challenge the state, sustaining a cycle in which terrorism and instability feed one another.

Set against other cases, Pakistan’s dilemma is unusually layered. Afghanistan’s terrorism is inseparable from insurgency and the long shadow of occupation. Iraq’s violence is largely sectarian. Nigeria’s Boko Haram reflects regional marginalization and a chronic governance vacuum. Pakistan, by contrast, faces a lattice of threats: nationalist insurgencies in Balochistan; Kashmir-oriented jihadists; transnational networks; and homegrown outfits like the Pakistani Taliban. Militancy is rooted in local grievances yet tightly knotted into regional and global geopolitics. Few states contend with terrorism that functions both as a tool of foreign policy and as an existential domestic threat.

Weak governance and economic distress deepen the problem. Chronic political instability, civil-military imbalances, and underdeveloped institutions open cracks that militants exploit. The effects are tangible: disrupted schooling, shuttered businesses, and a population living with ambient anxiety. Terrorism does not merely prey on weak governance; it reinforces it, hardening structural deficiencies that no short-term security operation can cure.

International debate often reduces these complexities to caricature. Critics label all non-state actors as terrorists; defenders cite Kashmir as a moral justification for patronage. Both arguments contain fragments of truth, but neither captures the central paradox: a state that once used militancy for strategic ends now faces blowback from groups it enabled, attempting to suppress the dangers without abandoning the very tools it long considered useful.

Regional dynamics further complicate the picture. The Afghan Taliban’s tolerance of the Pakistani Taliban sanctuaries underscores how Pakistan’s security challenge is entwined with South Asian geopolitics. Islamabad cannot resolve this solely through force. It needs sustained diplomacy—difficult amid historical mistrust and ongoing competition—with neighbors whose policies shape the battlefield.

The human toll is immense. Militancy depresses growth, deters investment, and corrodes trust in already-strained institutions. Children grow up traumatized; parents recalibrate daily routines around risk; communities normalize fear. Instability fuels militancy, and militancy deepens instability, leaving ordinary lives perpetually in the crossfire.

Breaking the cycle requires more than tactical gains. Pakistan must reconcile strategic priorities with internal security, restrict cross-border sanctuaries through pressure and diplomacy, and strengthen state capacity so that local grievances do not become recruitment pipelines. International partners should acknowledge the legacy of state-backed militancy while supporting reforms that enhance political accountability, broaden economic opportunity, and enable credible conflict resolution.

Pakistan’s terrorism problem is neither a simple moral question nor a purely external imposition. It is systemic, reflecting internal contradictions and regional entanglements. Understanding it requires moving beyond the easy binaries of “terrorist” and “freedom fighter” and confronting an uncomfortable truth: decades of strategic calculation, regional rivalry, and weak governance have produced a landscape in which violence is both a tool and a threat. Until those intertwined dynamics are addressed, terrorism will remain less an aberration than a persistent feature of national life—shaping the fate of millions who simply want safety, stability, and the chance to live without fear.