The ‘Red Line’ Strikes Back

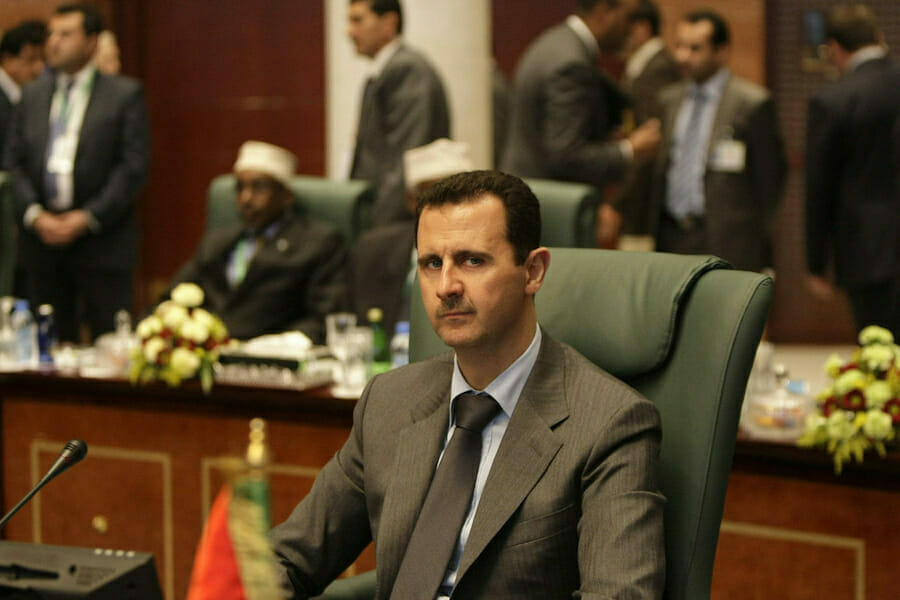

It remains uncertain just who is responsible for last week’s alleged chemical attack that left scores dead and scores more injured. Accusations have become a game of ‘he said, she said’ at the highest levels. The US and other Western governments hold the Syrian government accountable, while Russia and Iran blame the assault on Syrian rebel groups eager to ramp-up international condemnation against the Assad regime. The UN has negotiated for its monitors to inspect the alleged attack site, however, as the US mulls over possible action in Syria, it remains unclear how intervention would further US interests. In fact, it would seem that President Obama has potentially backed himself into a corner, and perhaps endangered US influence, as allegations of chemical weapons use in Syria tests his ‘red line’ policy.

Syria’s humanitarian crisis is unequivocally tragic yet the gulf in public opinion surrounding the conflict has widened over the years. US policy has consistently remained focused on containing Syria’s chemical weapon stockpiles, or at the very least deterring Assad’s forces from using chemical weapons during the ongoing conflict.

The recent attack in eastern Ghouta crossed the ‘red-line’ which many deem necessary for intervention. However, should it turn out that Syria’s rebels forces are indeed behind the August 21 attack as Russia suggests, questions will linger on how the US will and should react, potentially exposing a double-standard in US policy.

Nonetheless, US action in Syria – especially should it choose to circumvent the UN Security Council – not only endangers future achievement among the P5+1, of which some members are already wary following interventions in Iraq and Libya, it risks violating international law. Furthermore, US military involvement risks damaging any budding – albeit fragile – gains the US has achieved with the appointment of Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s newly elected president. An imminent sortie by the US hinders potential negotiations with the Islamic Republic down the road, particularly with regards to Iran’s highly contested nuclear program, as Rouhani and his cabinet form their policy.

It’s conceivable that American alienation with Iran’s new guard may force the US once again to standby its ‘red-line’ rhetoric should the Republic continue its nuclear enrichment program. On the other hand, should the US choose not to react in Syria or Iran, it puts at stake its influence in the region – and around the world -should future quagmires develop.

As tensions flare across the Middle East, the US will respond in one way or another. However, the practice of ‘red-line’ diplomacy, while well-meaning, constrains President Obama’s options, threatening to embroil the US in conflicts it has very little appetite for. It would seem that Obama would benefit to steer away from engaging in hardline tactics, however, a crisis as deadly as Syria’s makes it hard to stand idly by.