Sahel, the World’s Jigsaw

The Sahel is an eco-climatic zone located between the Sahara and the Sudanian savanna. It forms a belt of drier grasslands and acacia savannas, covering part or all of 10 countries from the Atlantic Coast to the Red Sea including Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea. Additionally, the region holds immense geopolitical significance.

And within this region, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad face some of the most significant challenges of any countries in the world. Until Mali’s withdrawal in 2022, these nations were collectively known as the G5 Sahel. The primary objectives of this regional organization, established in 2014, included promoting inclusive sustainable development, enhancing security, and improving the living conditions of the region’s inhabitants.

The G5 Sahel has attracted interest from countries beyond the immediate region. In 2017, Morocco rejoined the African Union after more than 30 years, a significant accomplishment for Rabat and Mohammed VI’s new foreign policy strategy in Western Africa. All five countries support Morocco’s territorial integrity and consider Western Sahara as part of it.

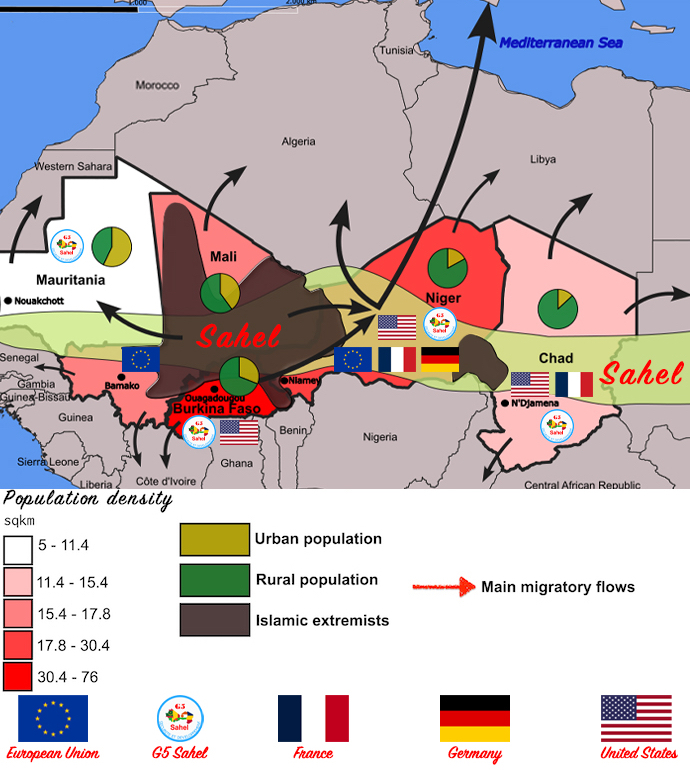

The latest Human Development Index, published in 2021 and ranking up to 191 countries, reveals the precarious situation faced by these countries. Mauritania ranks 158th, followed by Burkina Faso (184), Mali (186), Niger (189), and Chad (190). These nations are characterized by very low population density due to their vast territories, with the exception of Burkina Faso, which has extensive desert areas in the north. The urban population exceeds 50% only in the case of Mauritania.

Despite these challenges, the Sahel is a demographic time bomb, with a population projected to reach 200 million by 2050. This is due to about half of its population being under 15 years of age. Adding to the region’s complexities, it represents a crucial hotspot for mineral resources. According to the World Bank, the share of extractives (oil, minerals, gas, and coal) in GDP rents amounts to 15% in Mauritania (iron ore), 8% in Mali (gold), 9.5% in Burkina Faso (gold), 2% in Niger (gold and oil), and 20% in Chad (oil). Moreover, the region possesses coltan, manganese, lithium, and rare earth minerals, vital for many countries’ green energy portfolios. Industrial gold mining is rapidly expanding in the Sahel, leading to significant growth of artisanal and small-scale mining, which accounts for about 50% of total gold extraction.

Over the past decade, the region has gradually distanced itself from the West. It was not until 1960 that the United Nations adopted the Declaration on Decolonization, and in the same year, all five countries gained independence from France. Consequently, Western countries rushed to secure mineral rights from these newly independent nations.

Fast forward several decades, Russia and China are competing for influence and mineral rights. In Burkina Faso, the ruling junta awarded mining rights to the Russian firm Nordgold, owned by sanctioned Russian oligarch Alexei Mordashov, to exploit gold deposits estimated to be 2.5 tons per year. Similarly, the Chinese state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation has an ongoing operation in Chad to extract petroleum. In Mali, the Chinese firm Ganfeng Lithium acquired half of the Goulamina mine, one of the world’s largest lithium deposits. In Niger, China initiated the construction of an oil pipeline between Niger and Benin. Furthermore, in 2019, China provided $46 million to the G5 Sahel to support security and counterterrorism operations.

All of these developments indicate that the region sees its future aligning more with Russia and China than with Europe or the United States. In 2022, France withdrew its troops from Mali after nine years, and in February, France also withdrew from Burkina Faso after more than ten years. At the end of 2022, the UK announced the withdrawal of its troops from MINUSMA, a UN peacekeeping mission in Mali. Germany confirmed in May that its troops participating in MINUSMA would gradually leave the country by 2024. As a result, in June, the UN Security Council approved the complete withdrawal of UN peacekeeping forces from Mali by January 2024.

In the past two years, Mali went from being the country with the largest number of European troops to having practically none. This shift can be attributed to the fact that the region’s countries have determined that distancing themselves from Europe makes strategic sense. The only remaining strong presence for France in the Sahel is Chad, but the transfer of influence toward China and Russia appears irreversible. Moreover, the United Nations has long lost its respectability in the region. As Andry Rajoelina, the president of Madagascar, said during an interview in June, “Africa does not want to receive lessons from Western countries.” China will leverage this new regional context to carry out its Belt and Road Initiative, while Russia positions its Wagner Group to secure mining contracts in several countries, in Mali and Burkina Faso, in particular.

Adding to this chain of events is the political instability and armed conflicts that have become endemic to the Sahel. The expansion of violent extremism in the region has steadily increased. The number of civilian deaths and mass displacements is rising, and those fortunate enough are attempting to cross the Sahara Desert in search of refuge in Europe.

Multiple jihadist groups are vying for territorial control. Among these groups, Nusrat al-Islam operating in Mali and Niger is particularly troubling. It was formed from the merger of Ansar Dine, the Macina Liberation Front, Al-Mourabitoun, and the Saharan branch of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Additionally, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS) has a presence in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. Ansar ul Islam, a terrorist group born in Burkina Faso, is active in southern Mali. Finally, Boko Haram has extended its influence to Niger and Chad.

Political instability is a common thread in the region. Only two out of the five countries have democratic systems of governance, namely Mauritania and Niger, although the latter’s democracy is quite fragile. Malians hope to participate in presidential elections scheduled for 2024, but the memories of the coups in 2020 and 2021 are still fresh in their minds. In Burkina Faso, a coup took place in 2022, removing the president due to his “inability to address the Islamist insurgency,” as stated by his replacement, Ibrahim Traoré. In Chad, social instability quickly spread after Idriss Déby was killed while commanding his troops fighting insurgents in 2021, leading to his son, Mahamat Déby, seizing power.

Despite democratic setbacks and coups across the region, there is still hope, and Mauritania serves as a clear example. Since 2011, it has not suffered any attacks from Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, even though it shares a long border with Mali. Half of its population lives in urban coastal areas, and it is among the least densely populated countries, leaving a large territory that is relatively easy to manage.

The multidimensional approach and integration strategy implemented by Nouakchott has proven to be successful. The country’s economic future also looks promising. Growth accelerated from 2.4% in 2021 to 5.2% in 2022 with increased exports and new oil and gas deposits yet to be explored in the coming years. We will have to wait until mid-2024 when the political cycle in Mauritania ends to see if the country can become an example for its neighbors to follow.

Countries like Mali or Burkina Faso should exercise caution when combating terrorism and insurgencies. A cautionary case study to consider is Somalia, where armed militias were deployed to fight the Al-Shabaab terror group. While they have achieved moderate success in dealing with the Islamists, over time these militias can turn against the central government, leading to coups, civil wars, and social instability, thus repeating the history of sub-Saharan Africa.