Sudan Faces a Severe Crisis

In 2019, Sudan attracted growing international attention due to its internal political developments. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok heralded a democratic and liberal transition following decades of domestic conflicts and authoritarianism. Now Prime Minister Hamdok has to shore up the transition and overcome a severe economic crisis. Sudan’s fragmented political environment further complicates such a daunting endeavour.

On the Brink of Default

Long queues in front of bakeries and gas stations have become the habit across Sudanese streets. Fuel, food, and electricity shortages regularly sweep large swathes of the country, while soaring inflation, projected above 80 percent for 2020, has curbed families’ purchasing power. COVID-19 has brought the country further to its knees with an estimated GDP contraction of negative 7.2 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Protests calling for reforms continue unabated.

Years of economic mismanagement brought public debt to about $60 billion. This is the result of the expansion of the state budget propping up Bashir’s patronage system. For decades, Omar al-Bashir consolidated his rule through public spending on state-owned enterprises, the bureaucracy/military apparatus, and subsidized basic goods, which were largely imported. The system began faltering after 2011 when South Sudan’s independence from Khartoum curtailed Sudan’s vast oil reserves. In the following years, the government tried to compensate shrinking revenues with money injections, but the policy fueled the inflationary spiral that now cripples the country.

Now Prime Minister Hamdok needs the assistance of foreign donors to avoid default. The paramount issue for the Sudanese economy is the country’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism (SST) by the U.S. Department of State. The SST designation enshrines a set of sanctions that hinders foreign trade and investment, international loans, and access to IMF’s debt restructuring programme, i.e. the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative. Hamdok invested considerable capital lobbying Washington, but the SST designation removal is a cumbersome process.

Nevertheless, in June, international donors provided Khartoum an essential lifeline of $1.8 billion. Donations are expected to cover the cost of Hamdok’s Family Support Program. This $1.9 billion package was envisaged to provide $5 per month per person to approximately 80 percent of the population. Assistance came through a quid pro quo, as donors required the Sudanese government to cut its fuel subsidy, which alone drains roughly 30 percent of the state budget. The Family Support Program is indeed meant to cushion the impact of fuel price increases, expected between 44 percent and 70 percent by the IMF. Not surprisingly, the fuel subsidy cut has met and continues to meet resistance from relevant political actors, particularly from the streets and the cronies who benefit from subsidy-related corruption.

Many Fish, Small Tank

A key obstacle to the political and economic transition is the fragmented political landscape. While Prime Minister Hamdok rests upon solid support from Europe and the U.S., his domestic position is faltering. His attempted assassination in March was tangible proof of that. Opposition to the subsidy reform came from the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), the opposition movements that toppled Bashir last year and constitutes the political basis of the transitional government. But despite popular support around it, the FFC no longer represents an obstacle to Hamdok since internal power struggles have been curtailing its political weight.

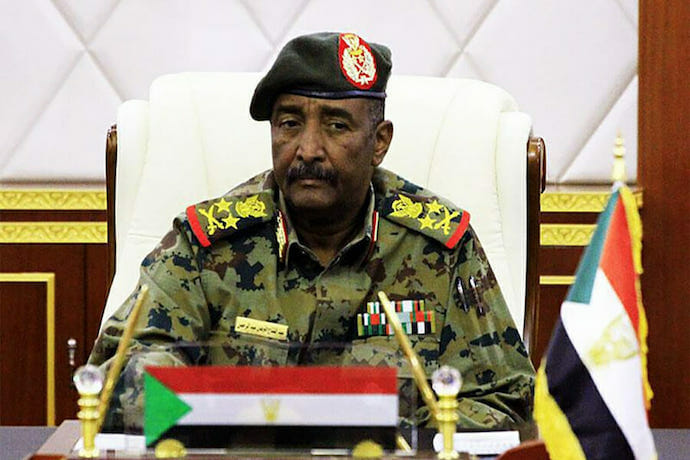

Generals, instead, pose a pressing threat to Hamdok’s government. Civilian leadership within the transitional government is more façade than reality. Lt. Gen. Abdal Fatteh al-Burhan is the Sudanese army’s chief of staff and chairs the Sovereign Council, the transitional executive body; this position makes him the de facto head of state. Burhan’s main rival does not come from the opposition but from the barracks as well. It is Lt. Gen. Mohamad Hamdan Dagolo, or “Hemedti.” He is the chief of the Rapid Response Force, a paramilitary force responsible for mass atrocities in Sudan and deployed to Yemen.

The military is a threat because it controls not only the means of violence but also a relevant share of Sudan’s economy. At the time of Bashir’s ouster, the public enterprises owned by his clique became up for grabs. Consequently, officials from both the military and the Rapid Response Force obtained shares in a plethora of economic sectors, including gold mining, oil production, commodity imports, telecommunications, and banking. Although the rivalry between Burhan and Hemedti helps keep them in check, the generals have forced Hamdok to backtrack on several domestic and international matters, including the Nile Dam dispute.

On top of that, Burhan and Hemedti can safely rely on the political and financial support of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Abu Dhabi has facilitated contacts between Burhan, Israel, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who met him personally during his recent trip to Sudan. Hemedti instead was able to deposit $170 million in the Sudanese Central Bank and launch his own programme of food distribution, in preparation for the 2022 elections according to experts.

The two Gulf monarchies swiftly transferred $3 billion to Khartoum when the military removed Bashir in April 2019 and continued delivering humanitarian and medical aid. From a regional perspective, this largesse should be interpreted in light of the broader geopolitical competition between Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the one side, and Qatar and Turkey on the other. Doha and Ankara had developed close relations with Bashir’s party, to the point of receiving a concession for the Port of Suakin in 2016. But after Burhan and Hemedti first entered the presidential palace, the project was suspended and a concession for Port Sudan is now under discussion with the UAE’s offshoot DP World. Despite the crackdown, Bashir’s network runs deep and his Islamist supporters continue to incite protests against the transitional government.

Another actor complicates this already intricate political landscape. The Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) is a coalition of armed groups from Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan, which long fought against Khartoum’s rule. In late August, the Sudanese government and the SRF signed a historic peace agreement ending decades of civil war. This was a priority for Hamdok and the international community. But what might look like an effortless achievement conceals paramount obstacles. Hailed by the rebel groups, the deal requires Khartoum to invest in the marginalized southern regions, integrate former combatants into the army through, and assign to these regions a representation quota in post-transition institutions. The first two measures will be particularly demanding for the transitional government at a time of budgetary crisis and they risk never to see implementation.

Towards an Egyptian or Malian Scenario?

Many actors crowd the political landscape seeking position and rent in the post-Bashir Sudan. On top of that, the COVID-related crisis poses a grave threat to Hamdok’s cash-strapped government, and severe hurdles might bring the population back to the streets sooner or later. If the situation were to boil over though, the military might decide to step in and replace Hamdok either directly or through a civilian figurehead. So far, two factors shield the prime minister from this scenario: his domestic and international support and the Burhan-Hemedti rivalry within the military.

The situation in Sudan dangerously resembles Mali and Egypt, which both ended up with a military coup. Like in Egypt, the Sudanese military controls the economy and enjoys strong ties with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, which have the means to reconcile Burhan and Hemedti. As in 2013 Egypt, the generals could reasonably wave the Islamist threat to orchestrate a takeover. Like Mali, Sudan faces an unprecedented economic crisis causing internal turmoil. The two countries also share a difficult-to-implement peace agreement with various armed groups whose bill will burden public coffers for years to come.

The fate of Sudan will primarily depend on the international commitment to the transition. Because Europe and the United States have not put their full political and economic weight behind Hamdok, the Sudanese generals and their Gulf sponsors will have the lion share in the transition. Much will also depend on Ankara and Doha’s willingness to harness Bashir’s remnants and Islamist supporters for political purposes. So far, Turkey and Qatar limited their intervention to medical aid boosting their public image. In any case, the prime minister will have to maneuver carefully to shore up the transition. The road ahead is bumpy and fraught with dangers.