The Achilles Heel of Chile’s COVID Response

Chile has been praised internationally for its successful COVID-19 response. Having vaccinated about 82.7% of its citizens against the coronavirus, Chile has one of the highest vaccination rates of any country in the world. The International Monetary Fund also lists Chile’s COVID response as one of the most financially generous among emerging markets.

However, a lesser-known aspect of Chile’s COVID response could have dire economic consequences for millions of Chileans and the country’s economy as a whole. Since July 2020, Chile’s Congress has approved three withdrawals of up to 10% from individuals’ private retirement accounts to offset financial strife during the pandemic. A vote to approve a fourth withdrawal will take place on September 28. Chile’s Congress should vote against a fourth withdrawal to prevent heightening the economic instability produced by the first three withdrawals.

Chile’s COVID response

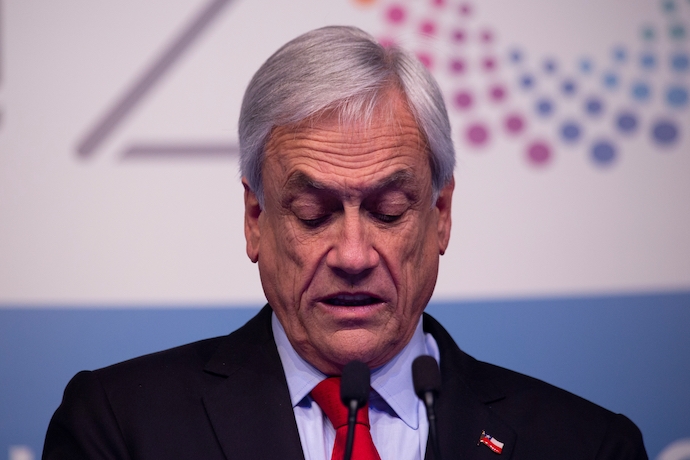

The Chilean government had a swift and multifaceted response to COVID-19. President Sebastián Piñera, the Ministry of the Interior and Public Security, and the Ministry of Health declared several states of emergencies that imbued the government with additional power to quickly and effectively combat the virus.

Among other policy measures, the government used this authority to mandate quarantines, curfews, and the movement of individuals and medical supplies between the country’s 16 regions and along international borders. Additionally, Chile’s government implemented an $11.8 billion dollar stimulus package and an Emergency Family Aid (IFE) program. The IFE seeks to provide wage subsidies to about 90% of the population.

In August, Piñera announced that the subsidy would be raised to as much as $316 dollars for women and $250 dollars for men until the program is terminated in December. This hoists the maximum subsidy amount above the $222 dollar poverty line reported by the government in March. However, critics of the IFE program say there is bureaucratic “red tape” preventing many in need from accessing these funds.

Lastly, Chile’s Congress has allowed individuals to complete three 10% withdrawals from their pension funds since the pandemic began. The privatized Chilean pension system, which began in 1982, requires all workers to deposit 10% of their income in individual retirement funds. Pension Fund Administrators, run by Chile’s principal economic groups, also invest these savings as a principal component of the country’s economic growth strategy.

The invisible costs

The ramifications of these withdrawals will be wide-reaching, both on an individual and national level. In the aftermath of the third withdrawal, several million Chileans—roughly one-third of pensioners—were left with practically empty retirement funds and about $49 billion was emptied overall. Congress has yet to create a way for individuals to replenish their funds. Though these withdrawals may have lessened financial hardship temporarily, they will cripple many individuals’ long-term financial security.

In Chile, those who have no pension to fall back on receive a government-issued solidarity pension. However, this fixed pension only amounted to $135 dollars in 2018. The current monthly minimum wage in Chile is $411 dollars. As it currently stands, one-third of pensioners, upon reaching retirement age—65 for men and 60 for women—will not be able to support themselves on a pension that is a third of the country’s minimum living wage. Additionally, a 2020 OECD report found that 53% of individuals in Chile would be at risk of falling below the poverty line if they forewent three months’ income. This suggests that millions of Chileans might risk falling into poverty if forced to rely solely on the solidarity pension.

This welfare disaster only becomes more concerning when one considers that Chile’s population is increasing in debt, age, and life expectancy. According to a Financial Market Commission report, Chile has experienced an increase in population debt in recent years. The report found that “23.4% of debtors had a financial burden above 40% of their monthly income.” This is more than twice the average burden for other countries with similar per-capita income. For those worried about defaulting on loans, the severity of lacking retirement funds is only magnified. Moreover, in 2050, 28% of Chile’s population is expected to be 60 years of age or older. With only 12.2% of the population being 65 years of age or older as of 2020, a large portion of Chileans will suffer the economic fallout of this policy sooner rather than later.

Chile’s successful economic growth is also intricately tied to the returns the country receives by investing the pension system’s savings. The country has seen a $2 billion dollar return from pension investments since the system’s instatement. According to the IMF, the amount removed from the first two pension withdrawals alone equals 14% of Chile’s GDP. This makes the three withdrawals a massively irresponsible policy decision, as it diminishes the financial capital Chile directly relies on for economic growth. Furthermore, Chile’s central bank has had to take extreme measures in recent months to curb inflation caused by these withdrawals. Indeed, inflation is predicted to reach 5.7% in 2021 — higher than it’s been for multiple generations.

Moving forward

Although Chile’s policymakers can’t undo the first three withdrawals, they can recognize the severe economic consequences of their actions and make a different decision this time around. On September 28, Chile’s Congress should vote against a fourth withdrawal. Instead of risking further financial instability for their citizens and country, Congress must turn their attention to how they will sustain a third of Chilean pensioners who find themselves with nothing to show for a lifetime of labor.

While Piñera recently announced that he will increase the solidarity pension above the poverty line to $223 dollars and extend the benefit to the bottom 80% of pensioners from the previous 60%, more must be done to address this issue. This new solidarity stipend still falls short of the country’s minimum wage. In the decades to come, Chile’s government needs to do much more to aid the millions of Chileans who will be unable to support themselves.