The Non-Division Of An Already Divided Jerusalem

As the Biden administration and the Bennett-Lapid government tussle over whether the U.S. will reopen its Jerusalem consulate, a central argument has emerged in the case for keeping the consulate shuttered. As noted at the very beginning of the House Republican letter opposing reopening the consulate and stressed by Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid in a press conference last weekend, the argument is that a U.S. consulate in Jerusalem would constitute a division of the city and erode Israeli sovereignty in its capital.

There are two elements that make this line of reasoning possible: one, that Jerusalem is currently undivided, and two, that reopening the consulate would functionally divide Jerusalem and represent a withdrawal of American recognition of the city as Israel’s capital. The problem with this line of argument, however, is that neither of these two elements is accurate.

The myth of a united Jerusalem is a powerful one. It stems from the half-century-old imagery that remains so meaningful of Israeli soldiers capturing the Old City; the trio of Yitzhak Rabin, Moshe Dayan, and Uzi Narkiss walking through its streets; paratroopers staring up at the Western Wall with awe and gratitude filling their eyes. When Israelis and American Jews speak of the imperative of Jerusalem never again being divided, they have in their minds the intolerable situation of Jews prevented from praying at or visiting the Western Wall, and the Old City’s gates standing as barriers to a Jewish presence.

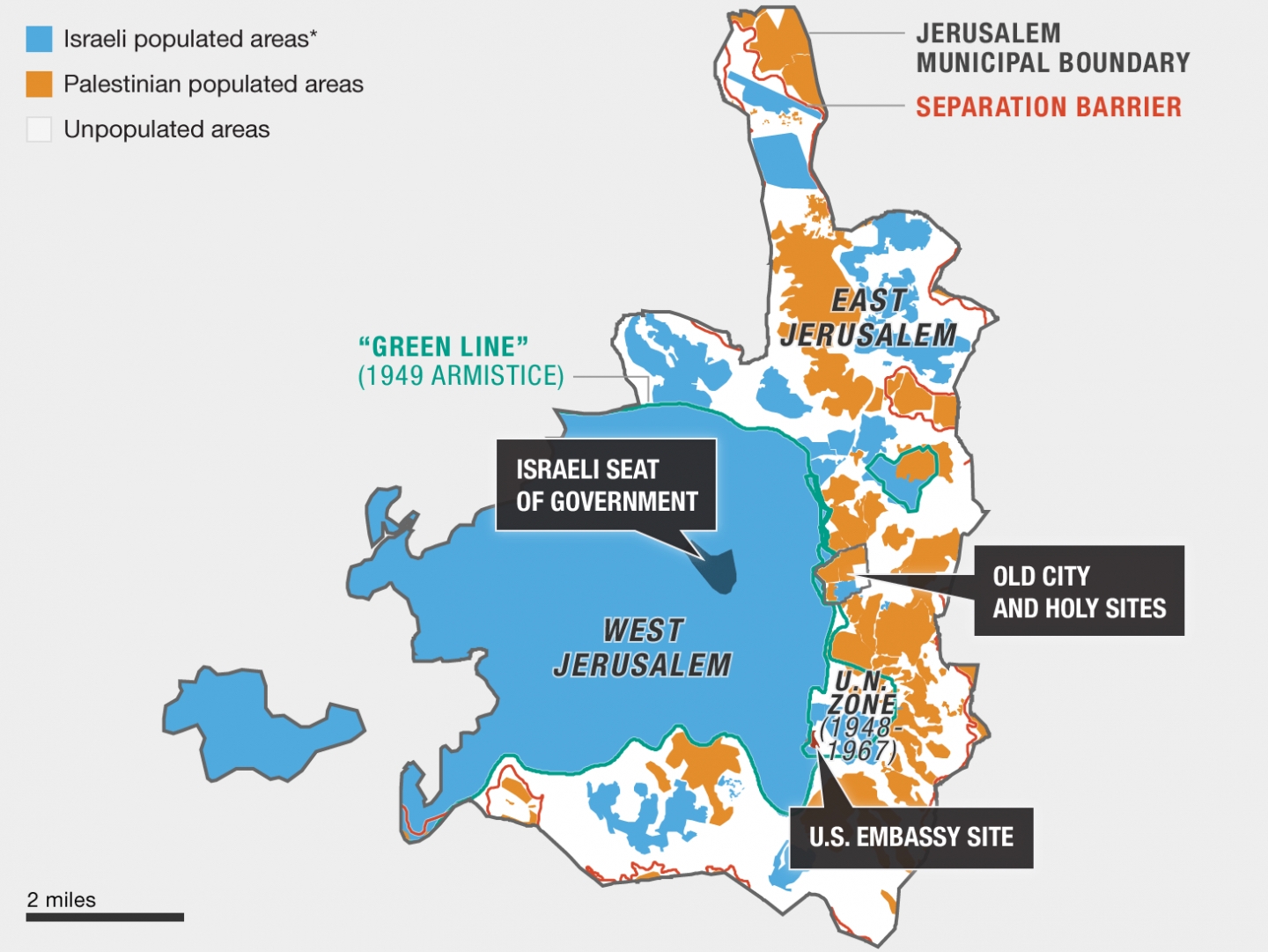

But in practice, a united Jerusalem goes well beyond this. The Jordanian East Jerusalem that Israel captured in 1967 when it united the western and eastern parts of the city was an area of 2.3 square miles, encompassing the Old City, Silwan, and a few other small neighborhoods. Yet today, the East Jerusalem section of Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries is 45 square miles, the result of Israel annexing 28 Palestinian villages to the Jerusalem municipality that were never part of Jerusalem.

The result is not a Jerusalem that is actually united; it is a Jerusalem that is very neatly and almost completely divided along a north-south axis between Jewish neighborhoods and Palestinian neighborhoods, with almost no sections of the city that are actually integrated or united. West Jerusalem—the part of the city that lies inside the Green Line and was controlled by Israel before 1967—is 99% Jewish; of the approximately 359,000 Arabs who live in Jerusalem, just under 5,000 of them live in West Jerusalem. In East Jerusalem, where you have a population that is 61% Arab and 39% Jewish, the populations live in homogenous neighborhoods, none of which can be defined as mixed. The notion of a united Jerusalem is a legal fiction, and the overwhelming majority of Jews never set foot in Arab neighborhoods or have any sense of what takes place in East Jerusalem beyond the Old City.

Going beyond demographics, both the Israeli government and the Trump administration had taken active and tangible steps to divide the allegedly indivisible capital. In Israel’s case, it erected a physical wall dividing the city by routing the security barrier through Arab neighborhoods of East Jerusalem that places two of them—Kafr ‘Aqab and Shuafat refugee camp—on the other side of the barrier, despite being inside Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries.

Current Housing and Construction Minister Ze’ev Elkin—now of New Hope but formerly of Likud—took this one step further in 2017 when he was Jerusalem Affairs Minister and proposed to create a separate municipality for those neighborhoods and formally split them from Jerusalem. The Trump Peace to Prosperity plan continued the policy of dividing Jerusalem by envisioning a Palestinian capital in Kafr ‘Aqab and Shuafat, which would have enshrined the current theoretically temporary and reversible division of the city in a permanent status agreement placing part of Jerusalem inside a future Palestinian state. Opposing the division of Jerusalem is a strong talking point, but it is nothing more than that—a talking point. In all manner of ways, Jerusalem is very much divided, so the question is not whether Jerusalem should be divided, but what the appropriate scope of that division should be.

What will not contribute to dividing Jerusalem is reopening the U.S. consulate. The consulate building, which is now officially the American ambassador’s residence, is squarely in West Jerusalem, sitting on Agron Street on a stretch between the prime minister’s residence on Balfour Street and the city’s highest-end hotels abutting the Mamilla pedestrian mall. There is no question that it is in sovereign Israeli territory, and no question that the U.S. recognizes it as such. To suggest that reopening a facility in a spot that is unambiguously and uncontroversially part of Israel and that the Palestinians themselves have no designs on would divide the city is a strange claim. In fact, one of the benefits of reopening the consulate in the old Agron facility is that it cannot be misconstrued as challenging Israeli sovereignty or suggesting a division of the city. If anything, it only strengthens the American recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and were the Israeli government inclined to be savvy about this, they would spin it as a win.

The U.S. can and should be even more explicit about what reopening the Jerusalem consulate does and does not mean. Pairing a consulate reopening with a clear statement from President Biden reaffirming the U.S. commitment to Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and reaffirming recognition of Israel’s sovereignty in Jerusalem will eliminate any confusion, whether honest or deliberate, that is currently swirling around the consulate issue. Doing so will also address the charge that reopening the Jerusalem consulate would violate the spirit of the Jerusalem Embassy Act by withdrawing recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or dividing the city; it certainly does not violate the letter of the act, which requires only relocating the embassy.

When President Trump proclaimed U.S. recognition of Jerusalem in 2017, he said the following: “The United States continues to take no position on any final status issues. The specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem are subject to final status negotiations between the parties. The United States is not taking a position on boundaries or borders.” Biden can borrow Trump’s statement verbatim, which would also be consistent with the Jerusalem Embassy Act’s identification of Jerusalem as a final status issue. Reopening the Jerusalem consulate is not about weakening Israel’s position in its rightful and historic capital, and the Biden administration should ensure that nobody can misconstrue its actions as such.

It is to both the American and Israeli sides’ benefit to come to an amicable agreement over how and where to reopen the Jerusalem consulate. If the Israeli government’s objection is not about having a diplomatic mission that serves the Palestinians—as Lapid clearly stated last week—but about what reopening the Jerusalem consulate would say about Jerusalem’s status, the Biden administration should do whatever it needs to do in order to take that objection off the table. Reopening the Jerusalem consulate is an opportunity to do just that, while reaffirming Israel’s connection to Jerusalem and American recognition of it.

This article was originally posted in Ottomans and Zionists.